Elected school trustees in Canada always seem to be in hot water and threatened with elimination. Ontario is the latest to identify the nub of the recurrent problem: the eroded local democratic governance, financial mismanagement, and dysfunctional behaviour of school boards. And it is presently confronting a critical decision on the future of elected trustees—now reduced to appendages of regional school boards.

In November 2025, the Ontario government of Doug Ford proceeded with Bill 33, the Supporting Children and Students Act, brushing aside fierce education interest groups lobbying to stave off school board governance reform.1 It’s all part of the evolving plan to improve the public responsiveness of school boards while planning to phase out elected school trustees. That turn of events made it clear: school governance reform is on its way in Ontario and may well spread to other provinces.

Eliminating trustees may, by default, lead to a “takeover of school boards,” but there is still a window of opportunity to flip the script and ensure that it becomes a structural reform in the direction of “taking back the schools.”2 This education reform policy paper makes the case that it’s an opportune time to survey the policy landscape and retire the existing model of centralized bureaucratic and unresponsive management.

Across Canada, the school system is groaning under the weight of its own bureaucracy. Centralized control, layered administration, and top-down governance have hollowed out the very institutions meant to serve students, families, and communities.3 For decades, provincial ministries and regional boards have been building an ever-expanding education “apparatus” that too often stifles innovation and isolates decision-makers from the classroom. The wisest choice has never been clearer: If we want schools that truly serve communities, we must flip the system—replacing top-down governance with bottom-up accountability rooted in the schoolhouse.

Today’s elected school boards suffer from an identity crisis. Over the past three decades, the school district apparatus in Canada has diminished as provincial governments have turned increasingly to pursue what education policy analyst Gerald Galway and colleagues in 2013 aptly described as “an aggressive centralization agenda.”4 Unlike municipal councils, which raise and control their own revenues, school boards have been stripped of their taxing powers and are funded almost entirely by provincial authorities. Education authority in Quebec remained centralized for curriculum and provincial assessment purposes. In major English Canadian urban districts, such as the Toronto District School Board and Vancouver School Board, elected trustees tend to flex their political muscles but soon discover that their powers are narrowly circumscribed under the current governance model. Subscribing to a “corporate governance model” also muddies the waters. Outside of the big cities, most boards are trained to act like an arm’s-length corporate board taking a “balcony view” and staying out of day-to-day operations.5

Role confusion over just how hands-on school trustees should be underlies many of the problems that plague boards. Misbehaviour, financial ineptitude, and internal rancor plague school boards, triggering outcries that they are dysfunctional and prompting periodic calls for their abolition.6 When a 2013 Canadian School Boards Association (CSBA) report warned that the remaining boards in Atlantic Canada were “sinking ships,” it sparked a defensive reaction and went largely unheeded.7 That essentially sealed their fate in the region.

Erosion of democratic legitimacy

Elected school boards came under fire for their inability to effectively represent local interests, and, over two decades, they gradually lost their democratic legitimacy. School trustees, once the linchpin of local democratic control, are an endangered species.

One of the early warnings that regional school boards were too big to be effective was issued in 2003 by Queen’s University education professor T. R. Williams. “Given the present size of boards, the traditional concept of an elected part-time trustee who can fully represent the interests of individual constituents is no longer viable,” he wrote. Merged “huge administrative units” became “so large and politicized” that they resorted to formulaic resource allocation—a model he argued was “woefully inadequate as a democratic institution.”8

Early warnings about the threat to local school autonomy fell on deaf ears. A 2009 report on Canadian school boards dismissed Williams’ critique and rejected calls for innovative school-based reform, including publicly funded autonomous charter schools. Ignoring concerns about eroding democratic accountability would prove costly in the long run.

School board consolidation—bigger, bureaucratic, and distant

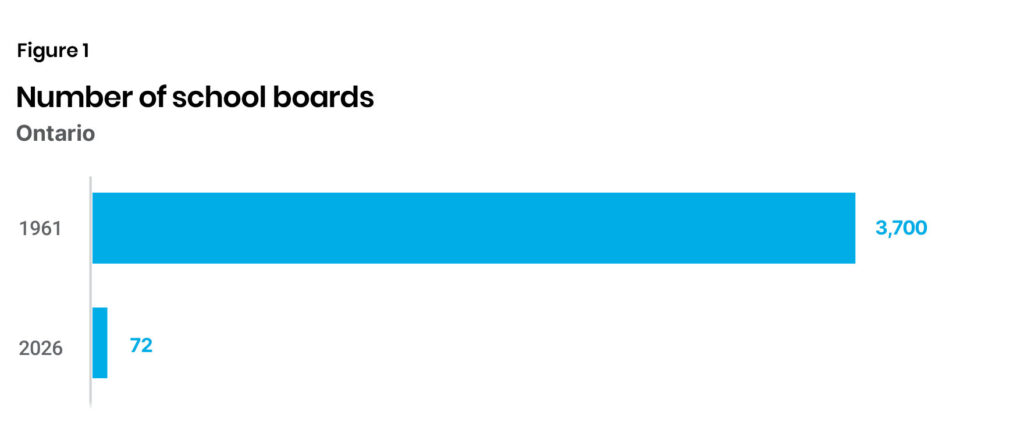

School district consolidation came in waves, the most dramatic of which transformed Ontario from the early 1960s to early 1970s.9 In 1961, Ontario Premier John Robarts inherited a system with an estimated 3,700 public and separate boards, many overseeing fewer than 100 students. The Robarts–Bill Davis modernization effort, known as “regionalization,” culminated in Bill 44 (1967).10 By 1969, the number of boards had been reduced from 1,358 to 192.11

This restructuring created today’s regional boards, along with layers of directors, superintendents, and administrators. Today, there are just 72 “local” public and separate boards in Ontario—a 98 percent reduction from 1961 (Figure 1).

School board restructuring and the Ontario Common Sense Revolution (1997–2002)

The 1997 Fewer School Boards Act (Bill 104) reduced the number of Ontario boards from 124 to 72, removed taxing powers, and reduced trustee stipends.12 From then on, the province asserted its authority over curriculum and evaluation, diminishing local autonomy and vesting increasing authority in district administration. Recent reforms, including Bill 33 (2025), continue this long-term trend.

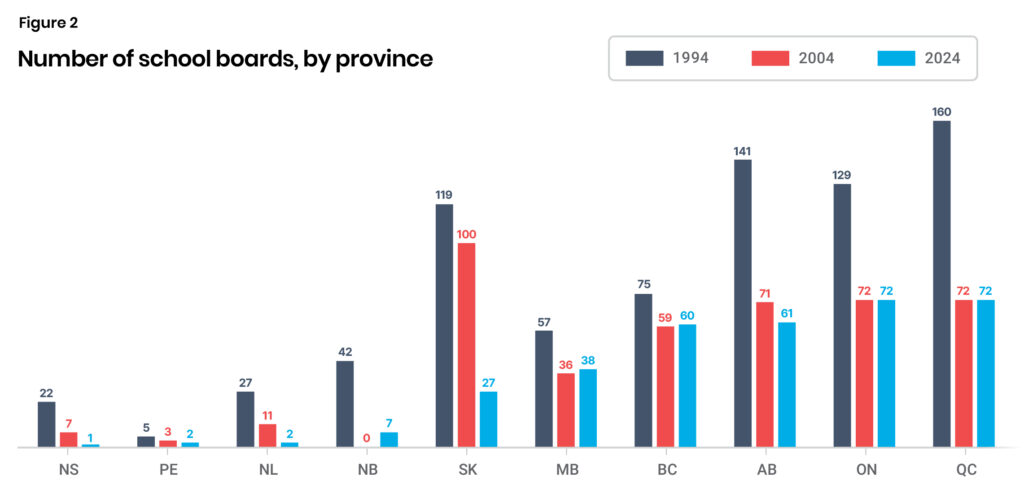

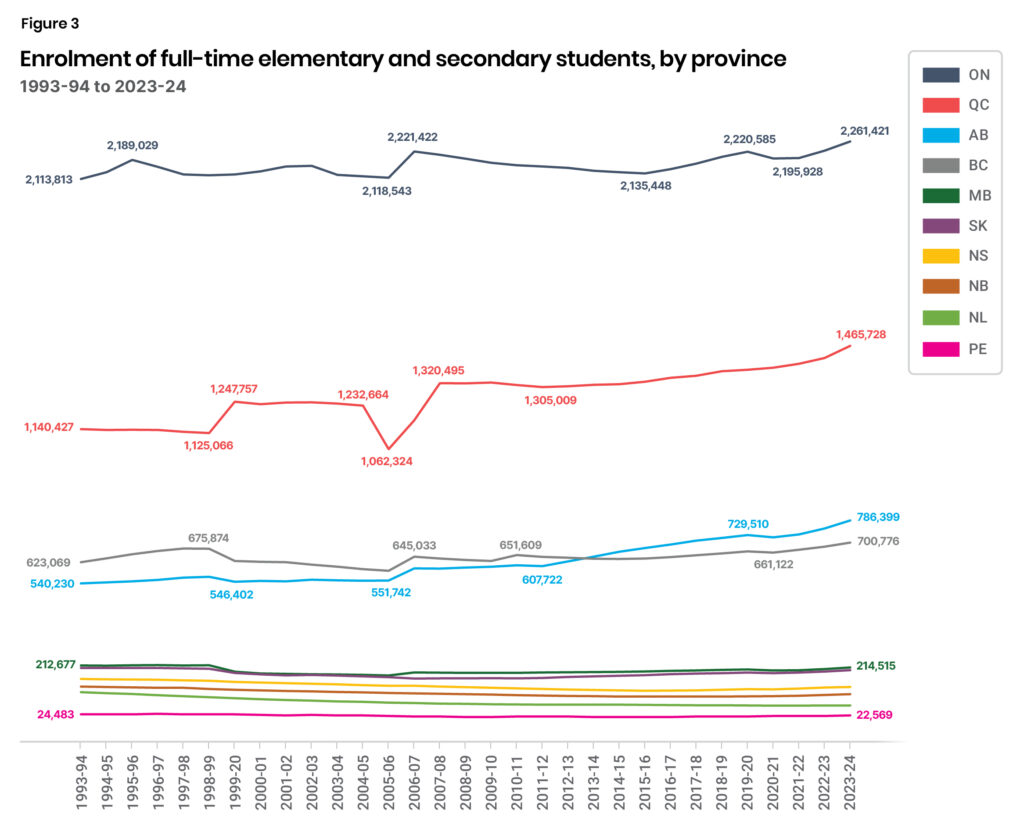

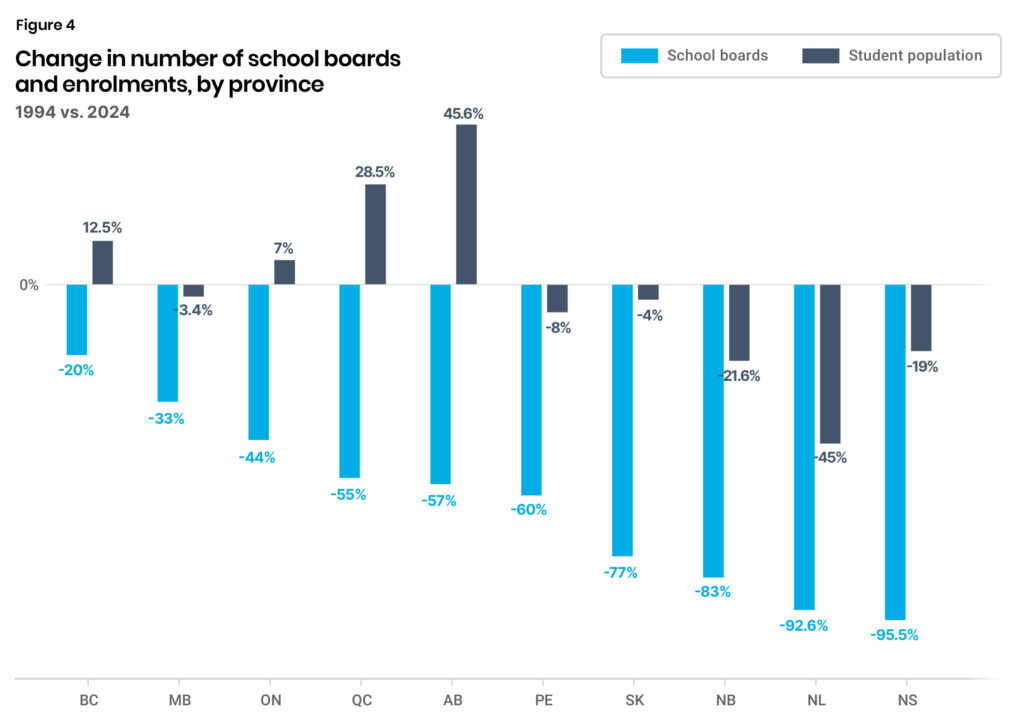

The amalgamations of the 1990s and early 2000s were not unique to Ontario. The numbers tell much of the story of school board reduction and the waning of local democratic governance. First, we look at declines in the numbers of boards in relation to student enrolments. Figure 2 shows the number of school boards in each province at the start (1994) to end (2004) of those amalgamations, as well as current numbers (2024). Figure 3 presents elementary and secondary school enrolments, which allow for three additional calculations. Figure 4 contrasts the percentage decline in school boards with enrolment trends between then and today; given relatively flat enrolments for two decades, the steep reduction in school boards is that much more pronounced.

Source:

Author’s calculations, based on Table A1 in the Appendix.

Source:

Statistics Canada (2025, 2001)13

Source:

Author’s calculations. (See Table A1 and Table A2 in the Appendix for the source data.)

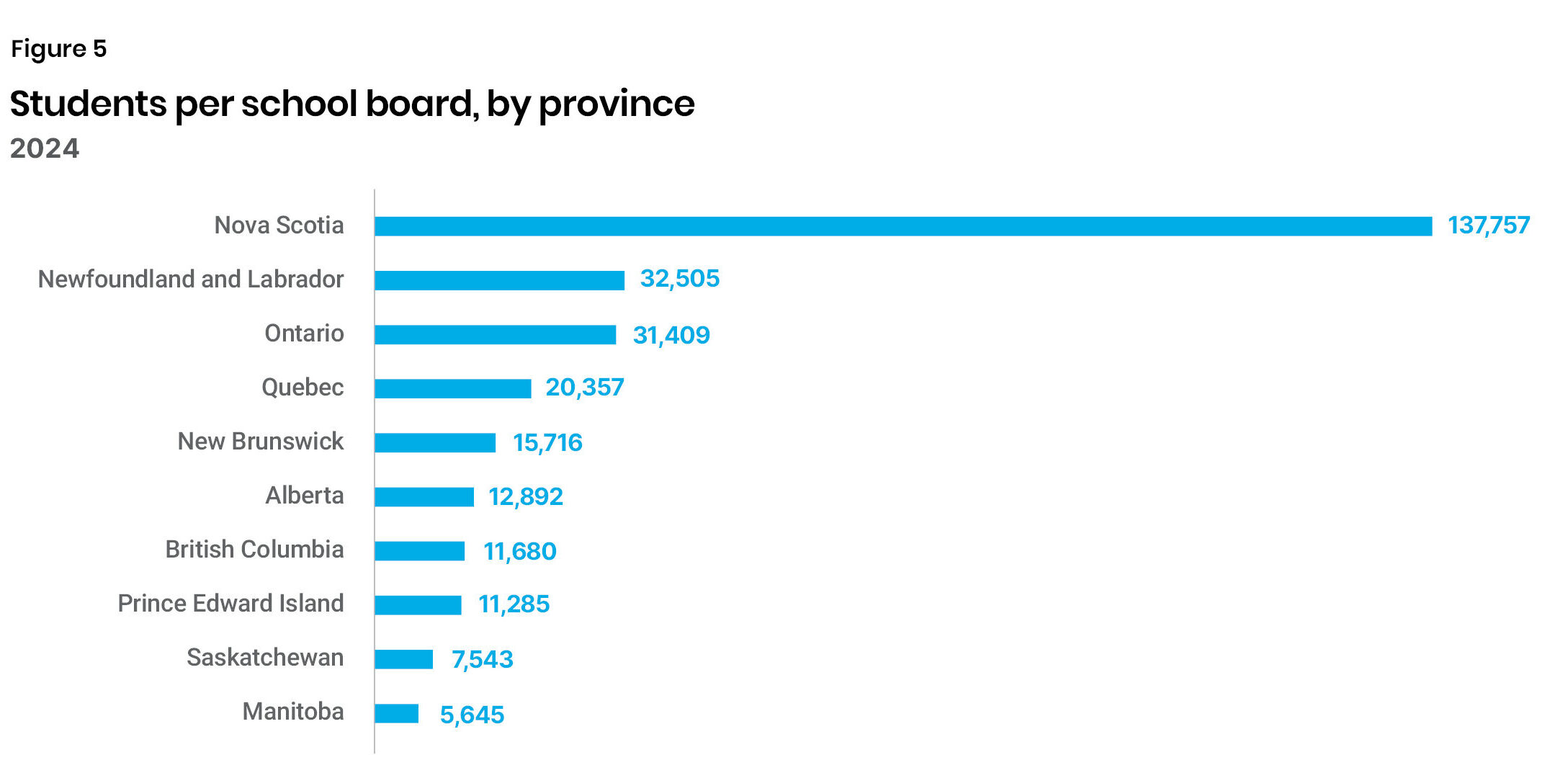

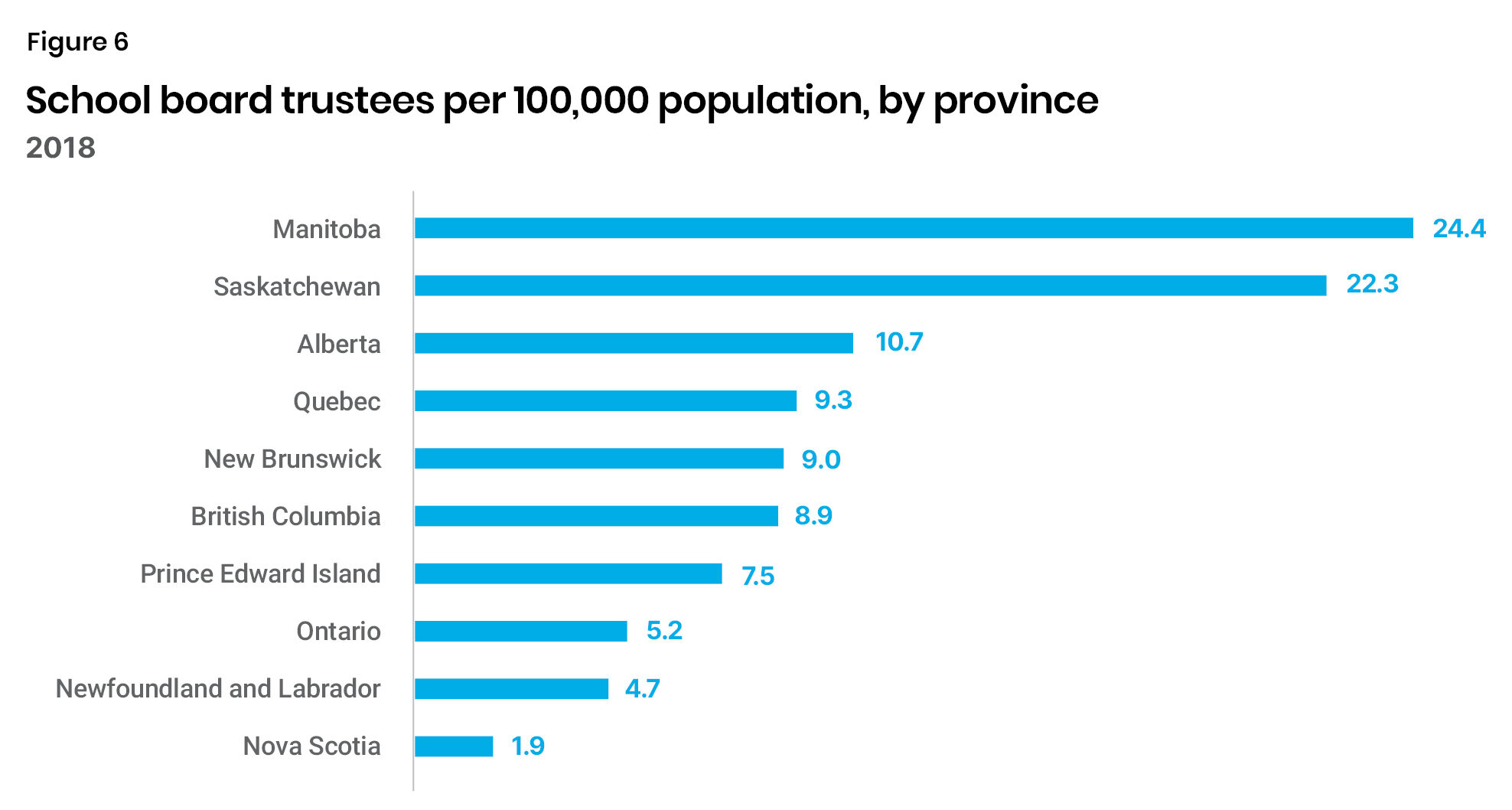

Consolidating the data allows us to assess the current state of local education governance. Figure 5 presents each province’s average enrolment per school board. Nova Scotia only has one elected school board—the Conseil Scolaire Acadien Provincial (CSAP), a constitutionally-protected francophone school board—and, thus, has 137,757 students per elected board (although most of these students are in the anglophone system, without locally elected trustees). The second least “local” school boards are in Newfoundland and Labrador, at 32,505 students per board, followed closely by Ontario. Conversely, Manitoba is the most local, at one school board per 5,645 students. And Figure 6 shows the number of trustees (and/or commissioners) per 100,000 residents, using the most recent accessible like-to-like data (2018). Again, Manitoba leads the way as most representative and Saskatchewan is close behind at, respectively, 24.4 and 23.3 school trustees per 100,000 people. By far the least representative is Nova Scotia, with less than two trustees per 100,000 Nova Scotians. (Please see the Appendix for a map and supporting data tables.)

Source:

Author’s calculations, based on Statistics Canada (2015) and CSBA (2018). (See Table A3 in the Appendix for details.)

Source:

Author’s calculations, based on Statistics Canada (2015) and CSBA (2018). (See Table A3 in the Appendix for details.)

The central flaw in the current system lies in governance. Provinces cling to structures that vest authority in ministries and school districts, creating distance between those who make decisions and those who live with their consequences. Instead of empowering principals, teachers, parents, and students, our system concentrates power in boardrooms, policy shops, and consulting circles.

Yet there is an alternative, one with deep Canadian roots. Edmonton was the pioneer. Under superintendents Rolland Jones (1967-1972) and, later, Michael Strembitsky (1973-1994), the city dismantled centralized control and shifted responsibility directly to schools. Budgets were devolved, principals were empowered, and parents were offered choice. By the early 2000s, more than half of Edmonton’s students were opting for schools outside their attendance zones, revitalizing once-declining institutions and proving that site-based management could deliver results.14

This approach—known as school-based management (SBM)15 —spread briefly to other provinces in the 1980s, including Ontario and Nova Scotia. Yet Canada largely ignored its own success story. The reform momentum for the Edmonton Model soon waned. Consolidation of boards, an explosion of administrative staff, and the rise of standardized testing all worked to recentralize power. By the late 1990s, only a minority of education employees were engaged in classroom teaching. The system, once again, was serving itself more than it served students.

The irony is that Edmonton’s model, introduced in the 1970s, gained global attention, even as it was neglected at home. Eventually New Zealand adopted “Self-Managed schools” in the late 1980s. The World Bank began championing SBM in 2003-2004 and promoted SBM across Asia and Africa, pointing out that education is far too complex to be delivered effectively through rigid, centralized hierarchies. Results have been mixed overseas, often due to resistance from entrenched interests, but the lesson remains: when authority is vested in communities, schools become more responsive and more accountable.16

Here in Canada, defenders of the status quo still claim that elected school boards are the bedrock of democracy. But, as Ontario educator Peter Hennessy once observed, school boards have become so disconnected from families that governments were compelled to create parent councils as a corrective measure—to give families some voice.17 Clinging to boards that no longer function as true conduits of local democracy is missing the point.

But the reality is that regional school districts with elected trustees are simply too big and more distant than ever from students, parents, teachers, and communities. The “band-aid” of parent councils has not worked, as school systems have further centralized and succumbed to so-called “controlling politics” of the “new managerialism” in public education.18

The solution is to restore democracy in school governance. A made-in-Canada model of community-school governance would start by replacing regional boards with autonomous school councils, made up of parents, educators, and community representatives.19 School budgets would be determined locally, with provincial funds following students to their chosen schools. Joint service consortia could handle special education services, transportation, purchasing, and most back-office functions, achieving efficiencies without stripping local schools of their authority. Regional development councils, involving trustees and municipal leaders, would provide oversight and ensure fair resource distribution.

Beyond structures: humanizing education

But decentralization, on its own, is not enough. Reform must also focus on people. If flipping the system means only re-arranging budgets and administrative charts, then the exercise will disappoint those the system is intended to serve. True reform must also humanize education, strengthen teaching, and deepen parental engagement.

First, schools must be scaled to human dimensions. Research from Britain and rural Canada shows that smaller schools foster stronger relationships, better engagement, and improved outcomes.20 The relentless consolidation of schools across rural and urban Canada has too often undermined these benefits, creating institutions too large to know students well.

Second, teaching must be restored to the centre of schooling. Teachers are not passive functionaries to be managed from above. They are the lifeblood of education. Democratic reform movements such as Flip the System, led internationally by classroom educators, remind us that teachers need both professional autonomy and accountability rooted in evidence.21 Re-establishing teacher agency is vital if reforms are to reach beyond structures and into learning itself. Teachers must regain professional autonomy, while joining in the important work of improving teaching and learning.

Third, parents must be embraced as true partners, not passive consultees. Too often, “parent engagement” is little more than lip service, framed in ways that reinforce school-centric authority. A family-centred approach— “walking alongside” parents rather than “building capacity”—is essential, if we are to break through and make schools more responsive at the school level.22

Instead of top-down mandates imposed by ministries and boards, we need to reclaim bottom-up accountability rooted in communities. Students, teachers, and parents would be at the centre, with administrators serving them—not the other way around.

Centralization has produced efficiency in name only, while draining vitality from schools. School board reduction was most pronounced in Atlantic Canada over the past fifteen years. Eliminating elected boards in Nova Scotia in April 2018 deepened the democratic deficit because it did not build in any apparatus to re-invigorate local voice or engagement.23 Parents felt sidelined, teachers felt disempowered, and students remain caught in the machinery of a system designed to manage, not to educate. Ontario now faces the same dilemma.

Flipping the system is not about nostalgia for one-room schoolhouses. It is about putting learning first. It is about building a responsive, democratic governance model. It is about reclaiming schools from bureaucrats, consultants, and central planners who rarely set foot in classrooms. Most of all, it is about ensuring that Canadian education reflects the voices of those who know children best—their families, their teachers, and their communities. The time has come to re-engineer public education—one school at a time.

Dr. Paul W. Bennett, Ed.D., is director of the Schoolhouse Institute and a contributor to the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. He has authored ten books, including The State of the System: A Reality Check on Canada’s Schools (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020)—and produced over two dozen policy research papers for six Canadian think tanks. Earlier in his career, Dr. Bennett was twice recognized for history teaching excellence, produced three nationally acclaimed Canadian history textbooks, served as an elected public school trustee, and headed two of Canada’s top-performing schools. More recently, he founded researchED Canada (2017-2025), taught as an adjunct professor, and served on the Canadian Association for Foundations in Education (CAFE) national board. He is also an education columnist for Brunswick News and a well-known commentator in the national media.

Who we are

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new education and public policy think tank that aims to renew a civil, common-sense approach to public discourse and public policy in Canada.

Our vision

A Canada where the sacrifices and successes of past generations are cherished and built upon; where citizens value each other for their character and merit; and where open inquiry and free expression are prized as the best path to a flourishing future for all.

Our mission

We champion reason, democracy, and civilization so that all can participate in a free, flourishing Canada.

Our theory of change: Canada’s idea culture is critical

Ideas—what people believe—come first in any change for ill or good. We will challenge ideas and policies where in error and buttress ideas anchored in reality and excellence.

Donations

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity, and all donations will receive a tax receipt. To maintain our independence, we do not seek nor will we accept government funding. Donations can be made at www.aristotlefoundation.org.

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy has internal policies to ensure research is empirical, scholarly, ethical, rigorous, honest, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge and the creation, application, and refinement of knowledge about public policy. Our staff, research fellows, and scholars develop their research in collaboration with the Aristotle Foundation’s staff and research director. Fact sheets, studies, and indices are all peer-reviewed. Subject to critical peer review, authors are responsible for their work and conclusions. The conclusions and views of scholars do not necessarily reflect those of the Board of Directors, donors, or staff.

Image credits: iStock

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER