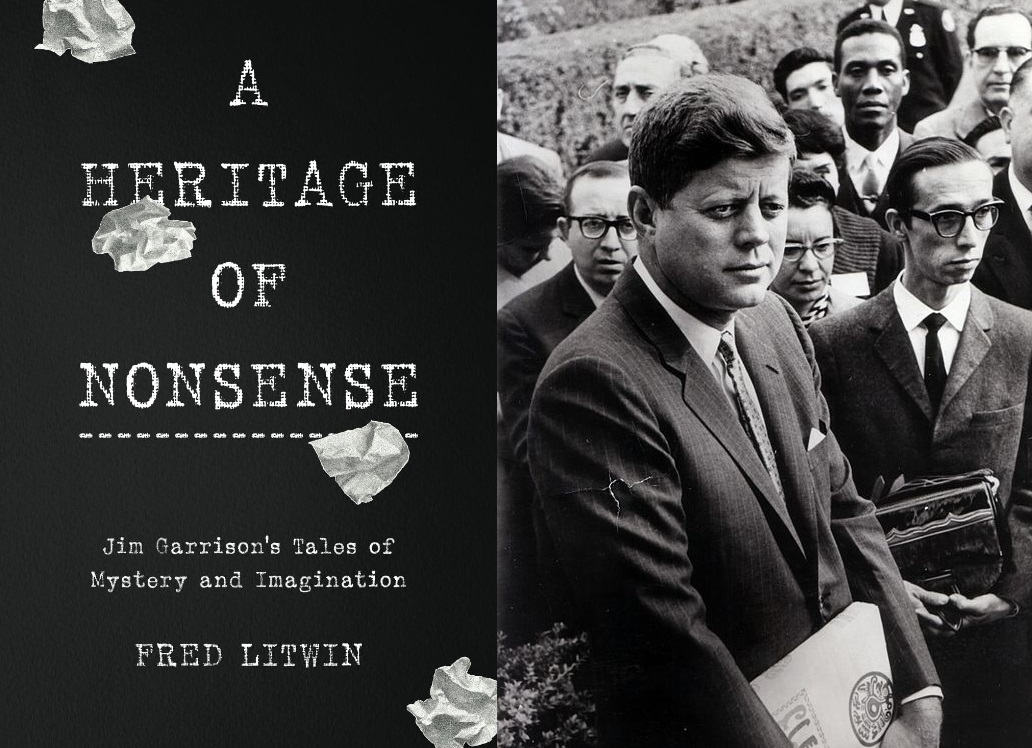

A Canadian expert on conspiracy theories reviews Fred Litwin’s A Heritage of Nonsense: Jim Garrison’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination (NorthernBlues Books, 2024. Available on Amazon for $22.78 CAD).

With the March 18th release of the President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection—all 2,566 entries—the JFK assassination is back in the news. Remarkably, but unsurprisingly, the lack of evidence to support various conspiracy theories is being peddled by popular YouTubers as “confirmation” of how deep these conspiracies run. It is time to move beyond these unfounded conspiratorial claims. And Fred Litwin’s latest book, A Heritage of Nonsense: Jim Garrison’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination, helps achieve this.

Many remember Oliver Stone’s Hollywood blockbuster, JFK—one of the most beautifully-crafted, controversial, paranoid, inaccurate, fallacious, and libelous biopics ever to light up the silver screen. JFK told the story of New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison, who in 1969 prosecuted local businessman Clay Shaw for the 1963 murder of the young president.

Stone pulled no punches scapegoating not only Shaw (who was promptly found not guilty) but also the Dallas police, the FBI, the CIA, the “Military Industrial Complex,” former President Lyndon Johnson, U.S. Air Force General Edward Lansdale, Kennedy’s own secret service detail, and a long list of politicians, businessmen, military figures, organized criminals, and innocent civilians for taking part in the murder of the century.

The film’s original promotional trailer called it “the story that won’t go away.” Indeed, Stone would spend the next three decades dredging up various versions of this dark saga despite the fact that his many films, TV programs, articles, interviews, and public speeches on the topic have been fact-checked by dozens of forensic experts, academics, and credentialed journalists and found to be meritless and deceptive, just like those of Jim Garrison which directly inspired Stone’s central life project—and all of this in the light of the hundreds of thousands of classified files that were released as early as 1998 in direct response to the accusations made in Stone’s 1991 movie.

Even so, this did not prevent Mr. Stone from recently repeating the same debunked claims in front of the United States Congress—flanked by fellow JFK “experts” and Garrison defenders, James DiEugenio and Jefferson Morley.

Most Americans are at least dimly aware that the government-appointed Warren Commission concluded back in 1964, with a comprehensive 888-page report and 26 volumes of depositions and evidence, that Lee Harvey Oswald killed President Kennedy without any assistance or outside compulsion. But this was not—and still isn’t—the explanation many people preferred, including Jim Garrison.

The evidence Garrison presented in court was nonsensical, irrelevant, and sometimes fabricated, which is why the jury took less than an hour to return a not-guilty verdict. A district court judge would later strike Garrison—who re-arrested Shaw on unsubstantiated perjury charges—with a permanent injunction to never prosecute the man again. This years-long legal fiasco would be laughable if it hadn’t destroyed many people’s lives and reputations and turned Garrison into a conspiracist messiah, thanks largely to Oliver Stone’s JFK blockbuster and a squad of persistently gullible Garrison apologists—including Jim DiEugenio, Joan Mellen, James Douglass, and Dick Russell—who swallowed Garrison’s wild accusations whole and ignored the man’s many legal witch hunts, ethical breaches, disproven claims, and paranoid delusions.

But Fred Litwin is thankfully not one of them. A retired computer systems marketing executive, music producer, and film festival director, the Ottawa-based Canadian author cut his political teeth promoting anti-nuclear causes in the years marked by JFK’s death, the Vietnam War, and the Watergate Affair. Initially fueled by left-wing political ideologies and conspiracist anxieties, Litwin’s worldview eventually migrated towards a centrist conservatism, an evolution he discusses in his two semi-autobiographical books: Conservative Confidential: Inside the Fabulous Blue Tent (2015) and I Was a Teenage JFK Conspiracy Freak (2018).

Litwin continued his work debunking conspiracy claims with On the Trail of Delusion: Jim Garrison: The Great Accuser (2020), an exposé of Garrison’s abuses of power and paranoid fabulations. This was followed by Oliver Stone’s Film-Flam: The Demagogue of Dealey Plaza (2023), a detailed critique of JFK: Destiny Betrayed (2021), Stone’s most recent attempt to skewer the Warren Commission with cherry-picked evidence and unfalsifiable question-begging. Through all this, Litwin has become a punctilious researcher, columnist, blogger, podcaster, public speaker, and news program commentator, correcting the errors and blatant lies of JFK buffs wherever these arise. Litwin has thereby joined the ranks of the leading JFK conspiracy debunkers alongside Gerald Posner, Vincent Bugliosi, Mel Ayton, and John McAdams, and is a shining example of how reasonable scepticism, meticulous investigation, and sober reflection can deflate paranoid delusions and bolster reasonable public discourse.

A Heritage of Nonsense is, as Litwin describes it, a companion piece to his earlier On the Trail of Delusion. Its title lampoons Garrison’s A Heritage of Stone (1970), an ambitious conspiracy treatise that likens President Lyndon Johnson to Augustus Caesar and blames the CIA for murdering Kennedy to prevent him from making peace with Castro’s Cuba, but says nothing about Garrison’s ongoing prosecution of Clay Shaw (perhaps to avoid being sued for libel).

Nonsense contains nine chapters of unequal length, each of which chronicles an additional episode of Garrison’s penchant for propinquity (i.e., guilt-by-association based on similar addresses, phone numbers, travel plans, acquaintances, etc.) and his fondness for garrulous grifters whose tall tales about Lee Harvey Oswald, Jack Ruby, Clay Shaw, and other “suspicious” figures could help him bolster his theories, whether or not such tales turned out to be true.

These stories can be divided into two categories: propinquities and grifters.

Four stories best capture the first category, which describes individuals who would be deemed marginal or irrelevant in the Warren Commission’s account of Kennedy’s murder, but have been conscripted by Garrison and his followers to act as key witnesses of, or accessories to, a murderous conspiracy. These include Larry Crafard, an itinerant worker who was briefly employed as a maintenance clerk and dog-sitter by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby, the man who would assassinate Lee Harvey Oswald. Both Mark Lane and Jim Garrison believed that Crafard was a CIA-trained Lee Oswald double who shot JFK from the infamous “grassy knoll” and then killed Dallas policeman J.D. Tippit to frame Oswald.

Another is Breck Wall, a Las Vegas entertainer and labour union representative whom Jack Ruby telephoned the day after Kennedy’s death to ask him to referee a conflict Ruby was having with rival nightclubs over their employment of unlicensed strippers. Though Wall had no other connection to Ruby, Oswald, or JFK, Garrison concocted a complicated theory—using Wall’s homosexual lifestyle, phone call from Ruby, and acquaintance with the mayor of Dallas—to connect him to Kennedy’s assassin(s). Indeed, the simple fact that Wall had visited Galveston at the same time as a gay man called David Ferrie—a New Orleans private investigator whom Garrison found suspicious—was enough to connect New Orleans’ whole homosexual underworld to JFK’s murder, even though Ferrie’s alibi was verified and confirmed by the FBI.

A third tale of propinquity is that of Bootsie Gay, a New Orleans poet and socialite who claimed she once saw a map of Dealey Plaza among the papers of David Ferrie when these were being removed from the offices of his employer, mob-connected lawyer G. Wray Gill, following Ferrie’s dismissal over Garrison’s accusations that Ferrie conspired to murder Kennedy. Although Bootsie Gay had a personal dislike of Ferrie, and her claims evolved over time, were unsupported by other witnesses, and proved nothing about the map’s intended purpose (if it ever existed), Garrison and his fawning biographers did not hesitate to use her as proof that Ferrie was part of a murderous plot.

A fourth and final story in this category concerns a January 1961 record of sale, co-witnessed by an unspecified “Oswald,” for the purchase of trucks from the Bolton Ford dealership in New Orleans. Rather than conclude that this obscure signature likely belonged to one of the world’s many other Oswalds, Garrison spun a story—inspired by the eccentric “Second Oswald” theory of philosopher Richard Popkin—in which the CIA was moving fake Oswalds around as early as three years ahead of Kennedy’s murder in Dallas, at a time when his future assassin was known to be residing in the Soviet Union with no indication he might return. Had Garrison exercised more caution he might have discovered, as Litwin did fifty years later, that a vehicle vendor named Oswald J. Schulingkamp, a business associate of the other man whose full name appears on the sales slip, happened to work just next door to Bolton Ford where a recent fire had damaged their own vehicles. (Here is where Litwin might have cued the Benny Hill chase music!)

The second set of chapters, which takes up a larger portion of the book, includes tales of grifters and charlatans who tried to ride the coattails of Garrison’s popularity by exploiting his thirst for sensationalist tattle. These include a schizophrenic gay priest and self-appointed psychic named Raymond Broshears. It was Broshears who claimed to have channelled the ghost of Lee Harvey Oswald and to have been intimate with the gay men whom Garrison, in his paranoid style, baselessly accused of murdering JFK.

Another is Rose Cherami, a diagnosed “mentally incompetent” petty criminal, arsonist, heroin addict, and prostitute who led the Louisiana State Police on a wild goose chase during a bogus 1963 drug bust, claiming to have worked in Jack Ruby’s strip club and to have advance knowledge of JFK’s murder, which she said was performed by Cubans. Described by many conspiracists as a silenced conspiracy witness (Cherami actually died of a severe concussion caused by an intoxicated roadside accident over two years after she reportedly “spilled the beans”), Litwin reveals that her insider knowledge and “suspicious” death were largely the invention of an untethered rumour mill churned by Jim Garrison, his investigator Francis Frugé, and a bevy of irresponsible scandalmongers.

A third example, the longest chapter in Nonsense, relates the detailed life story of a decorated U.S. Army intelligence officer named Richard Case Nagell who described himself to Garrison as a CIA-KGB double agent and associate of Lee Harvey Oswald who refused to take part in the CIA-sponsored coup d’état, and who owned a trove of incriminating evidence supporting such claims (none of which has ever surfaced).

Conspiracists chronically leave out the details of Nagell’s life story following his unlikely survival from a plane crash that left him with a traumatic brain injury, cognitive neuroses, depression, alcoholism, suicidal ideation, numerous arrests and mental health interventions, and countless attempts to gain attention and money, including by telling gullible researchers whatever they wanted to hear.

Much has been made of Nagell’s September 1963 arrest for discharging a weapon in a New Mexico bank, which he sometimes claimed was to save himself from being “silenced” like Oswald but was more likely a desperate attempt to receive treatment from a veteran’s hospital. Nagell’s stories were convoluted, ever changing, and mired in inaccuracies and clear fabulations, but nonetheless selectively mined by the Garrison gaggle for useful but unproven factoids. In the end, Nagell’s military and intelligence training, paranoid disposition, and cognitive skills and impairments all combined to make him a powerful magnet for the irrationally anxious who want to believe him, but the facts show him to be a broken man who knew very little and needed much help.

Litwin is a meticulous investigator who provides an abundance of primary documents to support his expositions, from old newspaper headlines to medical, court, and police documents. On the other hand, several of these are reproduced in low quality, making them difficult to read. One could also question whether there are too many of these in the text, as they impede the flow of the narrative and pepper the book with many awkward empty spaces.

Indeed, many of these replicated documents could have merely been quoted or paraphrased, with their images made available on his excellent website. In addition, although the book contains ample sourcing references, Litwin’s avoidance of numbered endnotes makes it hard for the inquisitive reader to identify his sources quickly and easily. The book is easy enough to follow, though sometimes the narrative gets bogged down in trivial or repetitive details where a shorter summation or clear explanation might have sufficed. Also, the book’s lack of an index is ironically reminiscent of the Warren Report and its 26 volumes—a major irritant to researchers who did not want to read through the whole thing to find a specific claim or passage. Finally, the book contains a sprinkling of spelling and typographical errors that might have been ironed out in a more stringent editing process.

On the whole, A Heritage of Nonsense is a thought-provoking and well-documented read for anyone interested in the JFK assassination and Jim Garrison in particular, as well as the origins and evolution of conspiracy theories. That includes the effects of circular reasoning, or the unwarranted influence of self-interested swindlers in shaping historical memory.

In short, Nonsense serves as a powerful rebuttal to Garrison’s falsely mythologized legacy as a crusader for justice and to the paranoid fables still being peddled by DiEugenio, Mellen, Douglass, Russell, Stone, and Garrison’s other apostles.

However, since this book was avowedly written as a companion piece to Litwin’s earlier On the Trail of Delusion, readers new to the Garrison drama would be advised to start there, and perhaps also to read Patricia Lambert’s False Witness, before sinking their teeth into this compendium of less well-known Garrisonisms.

Given that the minds of conspiracy-prone fabulists never tire of weaving new yarns into their grand speculative tapestries, this book is likely not going to be Litwin’s final opus. But it does give the reader sufficient reason to close the book on Jim Garrison’s ambitious fantasies, and to go stamp out other malicious wildfires.

Michel Jacques Gagné is a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, an historian and lecturer in the humanities department of Champlain College Saint-Lambert, host of the Paranoid Planet podcast, and author of Thinking Critically About the Kennedy Assassination (Routledge, 2022).

Like our work? Think more Canadians should see the facts? Please consider making a donation to the Aristotle Foundation.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER