Canada was a world leader in the abolition of slavery. So why does an NDP MP want the government to issue an apology?

One of the first petitions to Canada’s new Parliament has landed, and the topic is slavery. Endorsed by Gord Johns, an MP from British Columbia who managed to survive the recent NDP annihilation, it demands an apology to Black-Canadians from the Government of Canada: “Black Canadians have endured centuries of systemic racism, beginning with transatlantic slavery, followed by legalized segregation and ongoing institutional discrimination in policing, education, employment, housing, health care and the justice system.… The Government of Canada has yet to formally apologize.”

With only 125 signatures so far from a country of 40 million people, the petition is not exactly a milestone of populist politics. Nonetheless, the issues it raises are worth clarification.

The institution of slavery was not brought to the New World with the arrival of the European settlers. Slavery had been practised since time immemorial over most of North and South America. When the French arrived in what is now Quebec, they brought a few African slaves with them by way of their Caribbean outposts, but mostly they purchased Indigenous slaves from the Iroquois, the Illinois and other far-ranging tribes. These slaves became known as “Panis,” after the Pawnee tribe of Nebraska that furnished many of the captives.

The noted historian Marcel Trudel has estimated that, prior to 1760, the Panis made up two-thirds of all slaves in New France. Africans afterwards became more common, but overall numbers remained relatively small. New France lacked the plantations and mines that were worked by millions of slaves in Latin America, the American south and the Caribbean, so slaves were mainly personal servants and craftsmen.

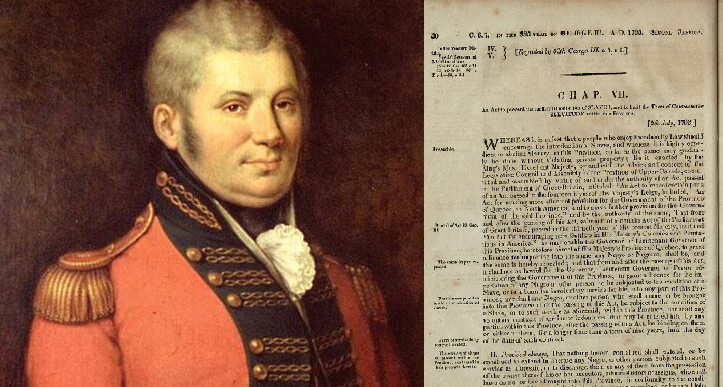

After the Conquest, more African slaves were brought in from the United States and the Caribbean, but the English conquerors also imported the philosophy of abolition, then starting to make headway in England and its colonies. In 1793, the Government of Upper Canada (now Ontario), under the leadership of Gov. John Simcoe, passed the Act Against Slavery, outlawing the importation of slaves, one of the modern world’s first anti-slavery statutes. In contrast, slavery was not abolished in the British Empire until 1834, in the United States until 1865 (with the end of a bloody civil war) and in Brazil in 1888. Far from being a mainstay of slavery and the slave trade, Canada was a leader in its abolition.

I grew up in Ottawa, Ill. (yes, that Ottawa). Now a wretchedly governed, highly indebted state, Illinois used to be “the land of Lincoln,” on the forefront of human freedom. Ottawa’s proudest boast is that it was a way station on the Underground Railroad. Ottawa’s inhabitants in those days were not afraid to defy state and federal laws, judges, courts and prisons to help runaway slaves get to — you guessed it — Canada.

Even after the legal end of slavery in the United States, Canada remained a beacon of hope for African-Americans. One of my adopted children is partially descended from a group of Black people who came to Saskatchewan from Oklahoma in the early 20th century, to escape mistreatment from both the whites and Native-Americans in their home state. They kept coming till the government of Liberal icon Wilfrid Laurier issued an order-in-council forbidding them to cross the 49th parallel.

There is, however, one blot on Canada’s record in the struggle for emancipation. Slavery was a widespread practice on the West Coast, from California to Alaska. Indigenous tribes sailed up and down the coast in their great war canoes to take captives for enslavement and human sacrifice. Even white sailors were sometimes enslaved. To their discredit, the governments of Spain, the United States, Canada, Great Britain and Russia preferred to look the other way, allowing Indigenous slavery to flourish on the West Coast until the 1890s. (If you think I’m making this up, read “Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America,” by the anthropologist Leland Donald).

If Canada should apologize to anyone, it should be to those Indigenous slaves’ descendants, who even today often experience diminished social status in their communities. To be honest, I don’t advocate for trans-generational apologies from those who have done nothing wrong to those who have experienced no wrong.

In the real world of politics, the demand for an apology is usually a hand extended not in friendship but in extortion. Former prime minister Stephen Harper learned that lesson when he made his famous apology for Indian residential schools, only to touch off a cycle of multi-billion-dollar class action lawsuits with no end in sight. We can’t change the past, so let’s try to be just in our own time. That’s enough for a human being to aim at.

Tom Flanagan is a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy and professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary. Photo: John Simcoe and the Act Against Slavery WikiCommons.

Like our work? Think more Canadians should see the facts? Please consider making a donation to the Aristotle Foundation.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER