In March 2025, the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC), a provincial government agency, announced “Dreams Delayed: Addressing Systemic Anti-Black Racism and Discrimination in Ontario’s Public Education System,” its action plan outlining its strategy “to address systemic anti-Black racism and discrimination in Ontario’s publicly funded education system.”1 According to the action plan, “Laws, policies, and practices that perpetuate prejudices, beliefs, stereotypes, and discrimination against Black people have been embedded in Ontario’s education institutions,” and the black population continues to “endure systemic discrimination and injustice” in public education.2

Yet, missing from the OHRC report is actual evidence of this systemic anti-black racism in education—as in, evidence of rules or policies that discriminate against black students. The report presents examples of individual acts of racism against black students, which are undoubtedly bad, but which do not constitute systemic racism. The report also suggests through statistical inference that black students are unfairly disadvantaged, but these inferences are also not actual evidence of systemic anti-black racism and often rely on logical fallacies or incomplete statistics. Unsurprisingly, given the shakiness of the OHRC’s premise, its conclusions and recommendations to the provincial government, school boards, and teachers’ unions are dubious at best.

According to the OHRC:

“Systemic racial discrimination in Canada and Ontario is indisputable. Black and other racialized persons experience disproportionate poverty, over-representation in child welfare and in the prison population, and under-representation in key sectors of society such as politics, administration, economics, and media institutions.”

It is a fallacy that disparities in outcomes, such as poverty rates, imply discrimination. For example, in Canada, women have had significantly longer life expectancies than men for over a century. But if disparities imply discrimination, we would have to conclude that Canada systemically discriminates against men. We would also have to conclude that the Canadian economy systemically discriminates in favour of certain racial minority groups including those of Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and South Asian backgrounds based on data showing that Canadian-born men and women of these groups have higher average weekly earnings than their white counterparts.3

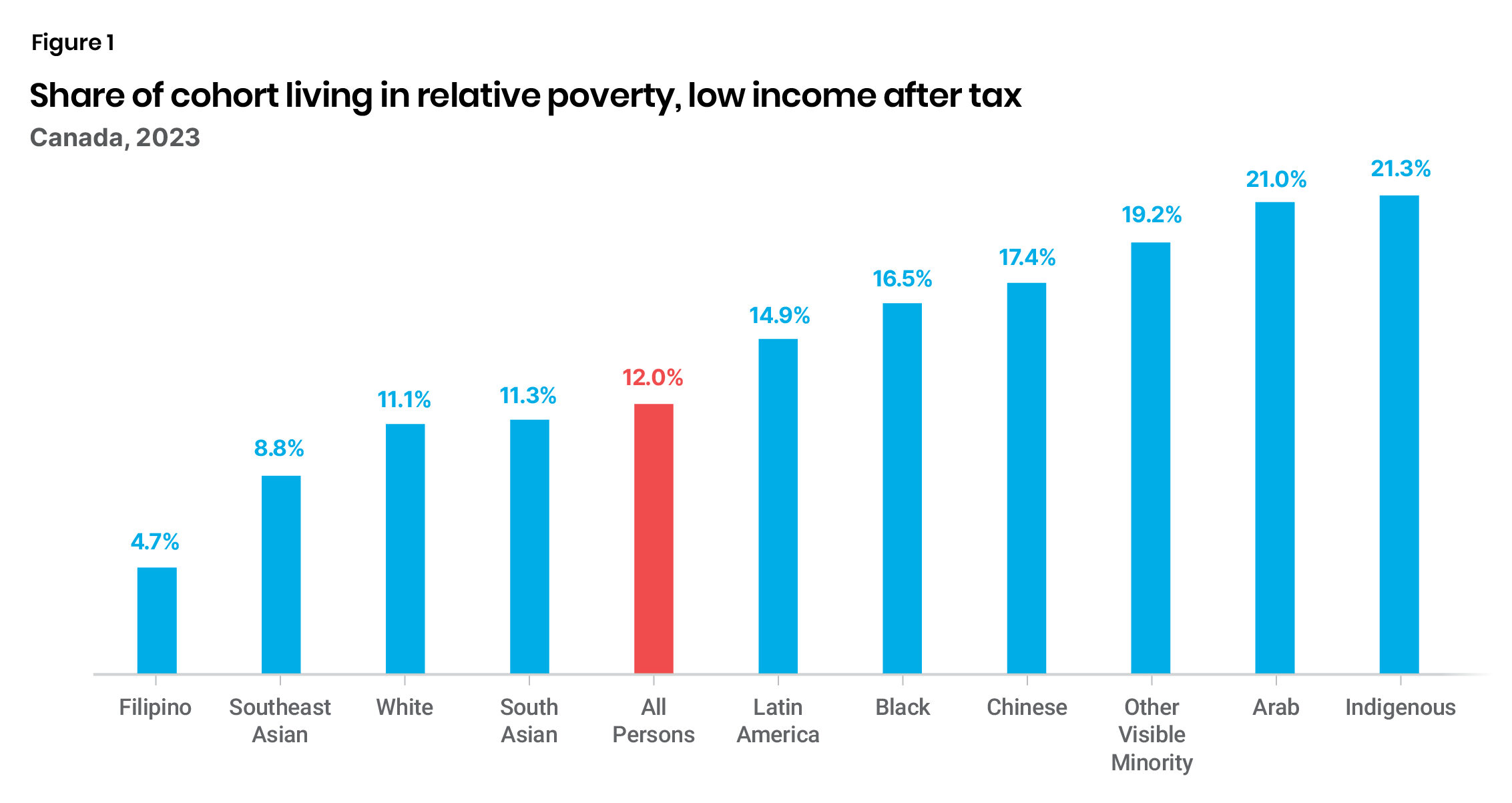

To address the OHRC’s example of poverty, while black people in Canada are more likely than average to live in relative poverty based on Statistics Canada’s low-income after-tax measure, so too are Canadians of Latin American, Chinese, Arab, and indigenous descent. Meanwhile, other minority groups— Filipino and Southeast Asian—actually have lower relative poverty rates than the white cohort (Figure 1).4

Sources: Statistics Canada Figure 11-10-0093-01

Therefore, no more can we conclude from poverty statistics that black Canadians face systemic discrimination, than we could conclude that Canadians of Latin American, Chinese, Arab, and Indigenous descent are also harmed by systemic discrimination while Canadians of Filipino and Southeast Asian descent systemically benefit from racial discrimination.

This same argument could be made about the OHRC’s claims of black overrepresentation or underrepresentation in certain areas. They are not evidence of systemic anti-black discrimination; disparities in outcomes, in and of themselves, do not reveal causal relationships.

The history of slavery is mentioned numerous times through the OHRC action plan, and it is implied that this historical injustice continues to drive anti-black outcomes and discrimination today. For example, the OHRC report states:

“[A]nti-Black racism in Ontario has specific historical roots in European colonialism and the trans-Atlantic slave trade, in which humans were treated as saleable goods in the triangular trade between Europe, Africa and the Americas. Anti-Black racism has been manifested in the legacy of the current social, economic, and political marginalization of African Canadians in society…”

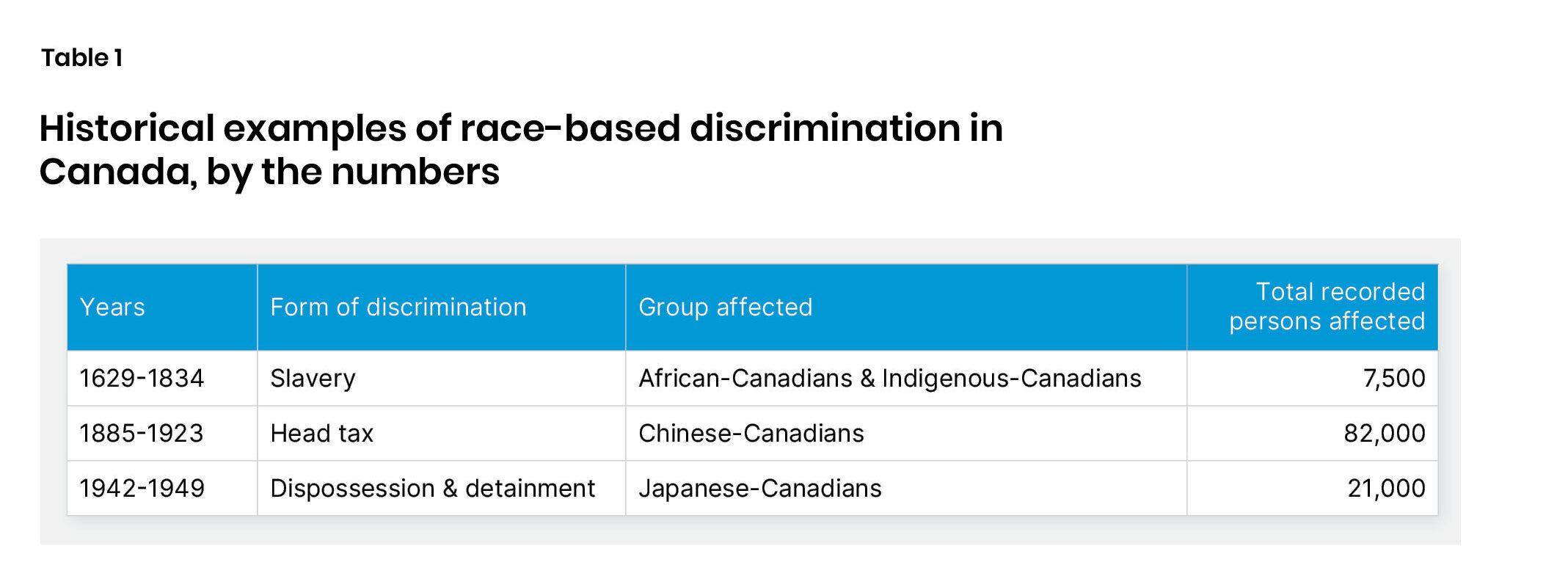

In truth, it is a significant stretch to tie historical slavery in Canada to outcomes today. Thankfully, laws began restricting slavery in Canada as early as 1793, with outright abolition realized in 1834. Canada’s total slave population—across two centuries—amounted to at most 7,500 people. The majority of these slaves were in New France, of which only 35 percent were black.5 Notably, Canada’s historical state-sanctioned, race-based injustices also included charging a head tax on approximately 82,000 Chinese between 1885 and 19236 and forcibly expelling approximately 21,000 Japanese-Canadians from their homes, confining them to internment camps, and dispossessing them of their property between 1942 and 1949 (Table 1).7

Sources: Sources: Gann (2025), Petrov (2021), and Robinson (2017)

Trying to link slavery that was abolished in 1834 to outcomes for black Canadians today is like arguing that Canadians of Chinese or Japanese backgrounds are systemically disadvantaged today because of the head tax of over a century ago or the internment of Japanese-Canadians around the Second World War. Yet it would be difficult to argue that Canadians of Chinese or Japanese backgrounds face systemic discrimination in Canada today, whether in the education system or elsewhere. As noted in the previous section, Canadian-born men and women of Chinese and Japanese backgrounds have higher average weekly earnings than their white counterparts – surely not the expected outcome in a society rigged to disadvantage them. Of course, that their earnings are higher is also not evidence that society is rigged in their favour: as mentioned previously, disparities in outcomes do not imply discrimination.

In the OHRC report’s introductory section on the black population in Canada, after mentioning slavery, disparities in outcomes, and segregated schools in the 19th century, the OHRC cites as evidence of ongoing anti-black oppression that—according to Statistics Canada—reported hate crimes targeting the black population increased 28 percent year-over-year in 2022.

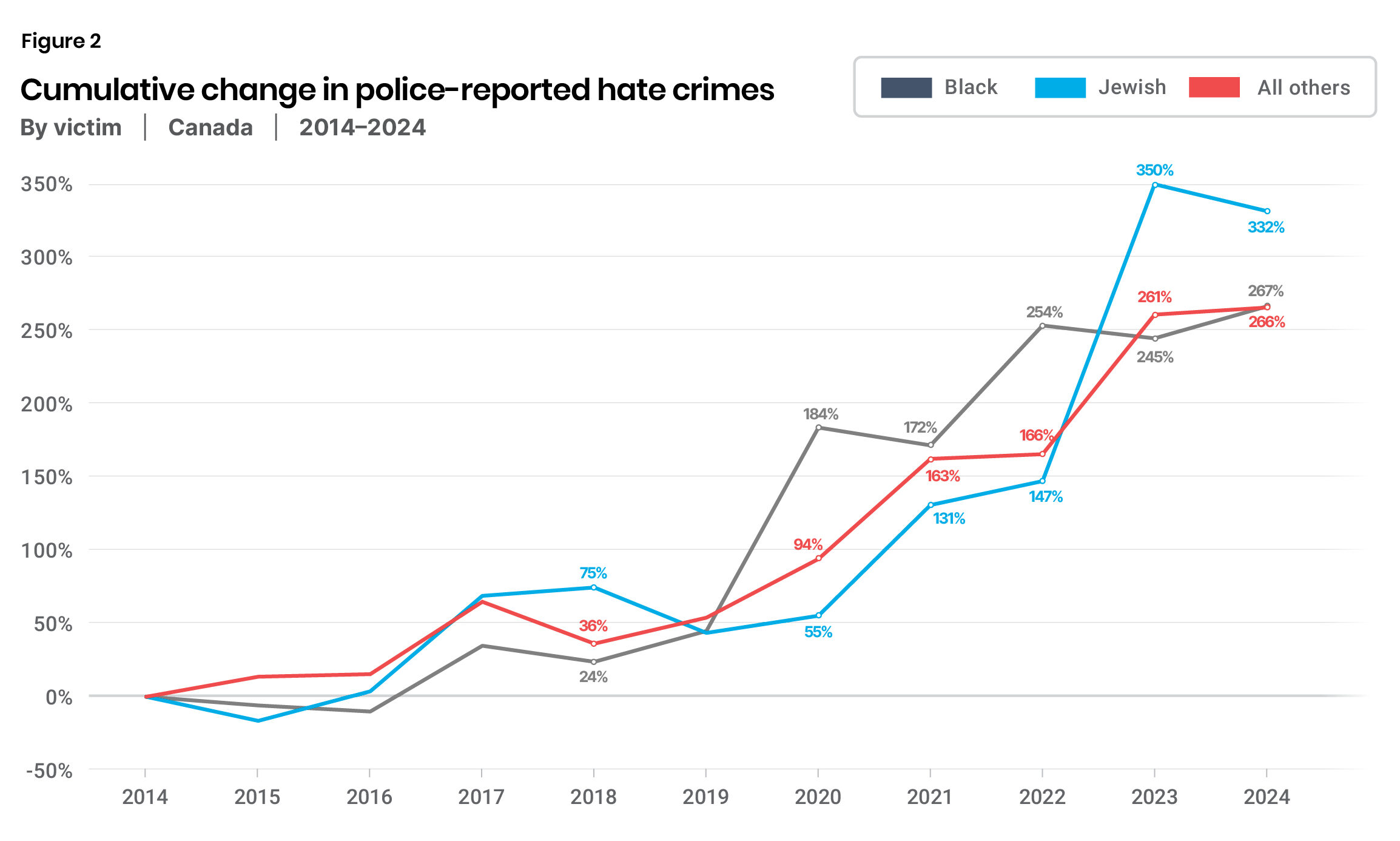

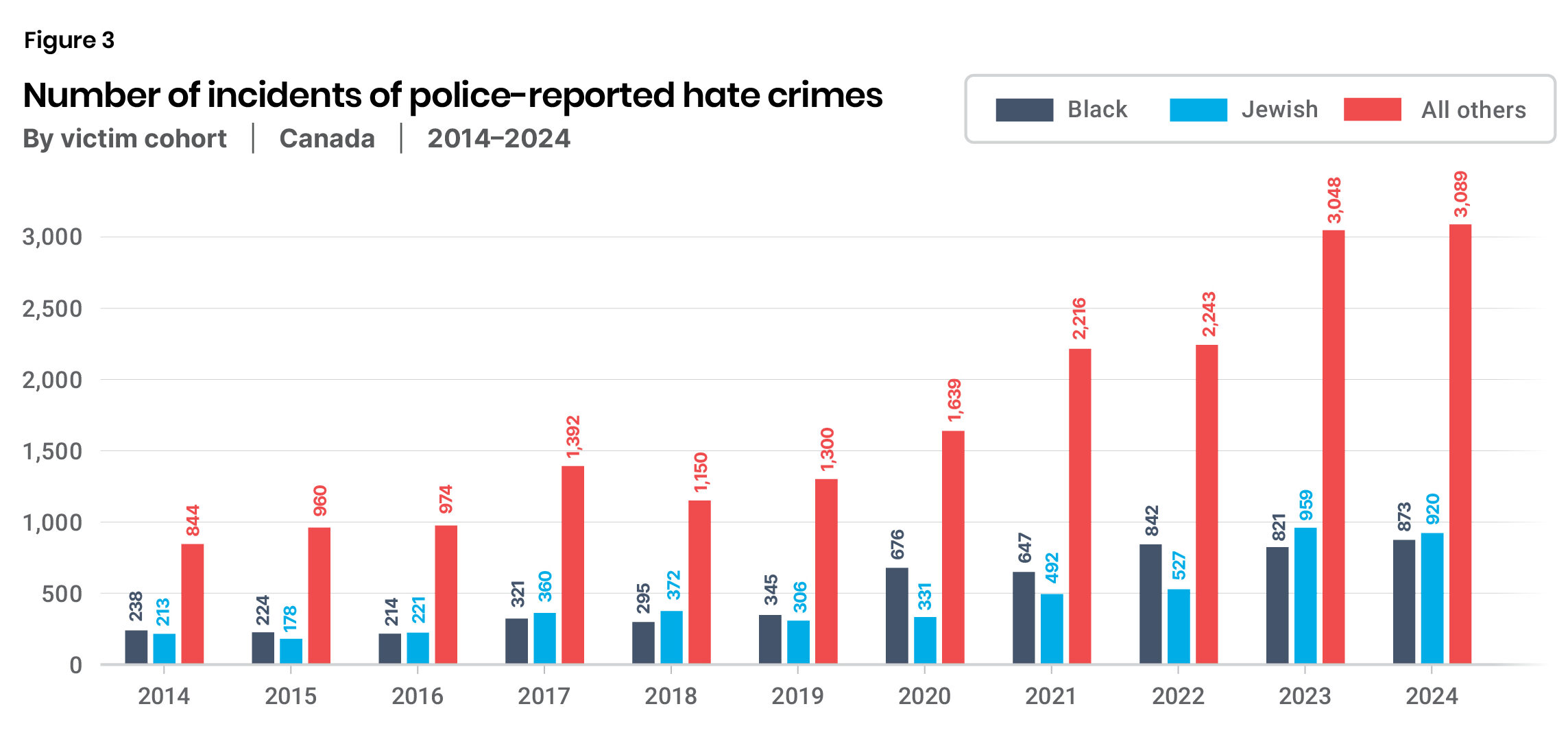

However, the OHRC failed to mention that police-reported hate crimes targeting the black population were actually down year-over-year the years immediately before (2021) and after (2023)—even as total police-reported hate crimes against Jews and all others were up in 2021 by 48.6 percent and 35.2 percent, respectively, and in 2023 by 82 percent and 36 percent, respectively. Other cohorts, like the Jewish population, have experienced a steeper rise in hate crimes against them, and the rise in hate crimes against the black population have been consistent with all other cohorts—267 percent and 266 percent, respectively, from 2014 to 2024 (Figure 2).8 Figure 3 shows the absolute number of incidents. (Of note, the Jewish population is about one-quarter the size of Canada’s black population.) In short, hate crimes have been rising across the spectrum, regardless of cohort; the data do not support claims of anti-black oppression in Canada.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on Statistics Canada (2025), Table: 35-10-0066-01 (formerly CANSIM 252-0092)

Sources: Author’s calculations based on Statistics Canada (2025), Table: 35-10-0066-01 (formerly CANSIM 252-0092)

A prominent theme in both the body and recommendations of the OHRC’s report is that the school curriculum must be reformed to be more inclusive of blacks. For example, it says the Ministry of Education must ensure “representation of Black intersectional identities in curriculum materials, textbooks, and supplementary resources” and “in collaboration with Black communities, parents, and community organisations, research and integrate diverse Black narratives, histories, and contributions in the K to 12 curricula as core subject disciplines.”

The OHRC also posits that “anti-Black racism in Ontario has specific historical roots in European colonialism and the trans-Atlantic slave trade,” and the continued marginalization of the black population has “led to systemic anti-Black racism being embedded in power structures which perpetuate advantages for people of European descent, such as curriculum focused exclusively on European history, or setting aside the scientific or literary contributions of those not of European descent.”

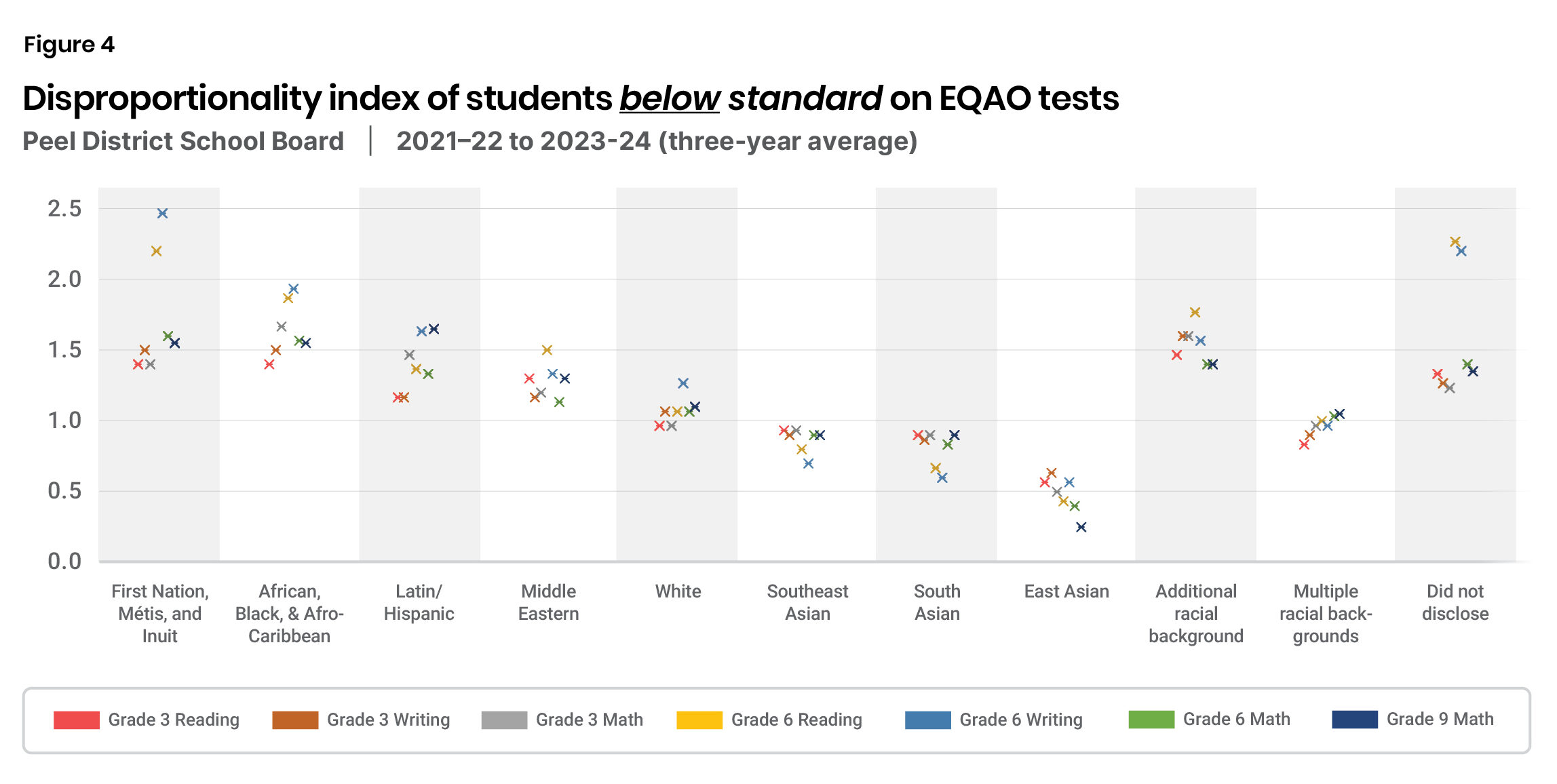

Yet in reality, there is no evidence that “people of European descent” have any unfair advantage in Ontario’s education system. For example, in 2024, the Peel District School Board reported that students from East Asian, South Asian, Southeast Asian, and “multiple racial” backgrounds were more likely than their white counterparts to reach provincial standards on average over the past three years in each of six standardized tests administered by the provincial agency, Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO): grade three reading, grade three writing, grade three mathematics, grade six writing, grade six mathematics, and grade nine mathematics (Figure 4; Appendix Table A1). Students from those same backgrounds were also less likely on average than their white counterparts to receive school suspensions.9

Sources: Note: Lower score = better performance; 1.0 = average

Source: Peel District School Board (2024)

Again, disparities do not imply discrimination, so it cannot be said that these minority groups who academically outperform white students on average receive special benefits from systemic discrimination. Where is the evidence that “people of European descent” are advantaged at everyone else’s expense?

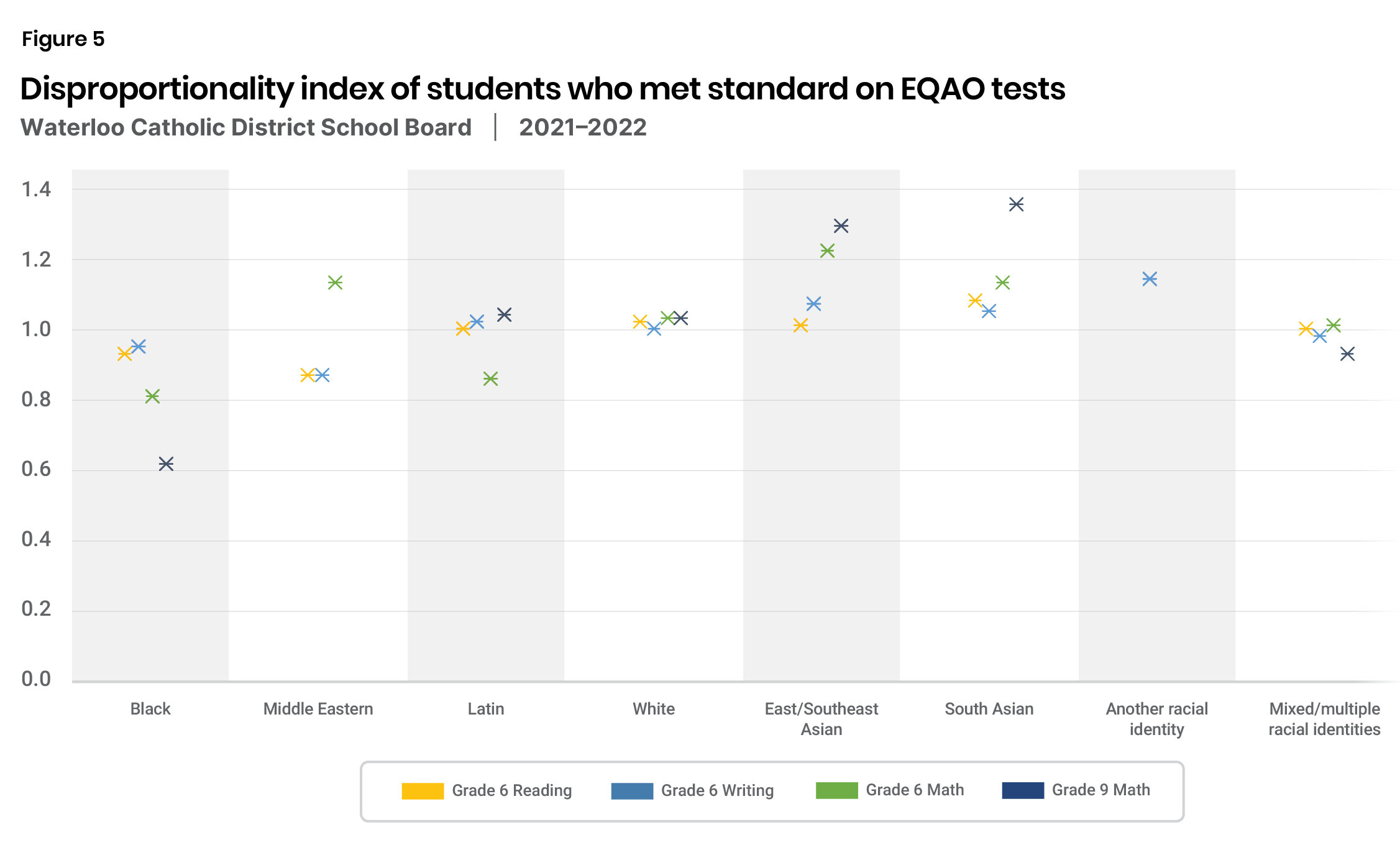

Other school boards have published similar results. In the Waterloo Catholic District School Board, students of South Asian, East or South-East Asian, and Latin backgrounds were more likely to achieve provincial standards in grade nine math than white students in recent EQAO tests. South Asian students also outperformed white students on average in grade six reading; South Asian, East or South-East Asian, and Latin students outperformed white students in grade six writing; and East or South-East Asian, South Asian, and Middle Eastern students outperformed white students in grade six mathematics (Figure 5; Appendix Table A2).10

Sources: Note: Higher score = better performance; 1.0 = average

Source: Mendonca & Roberts, et. al. (n.d.)

While not all school boards publish complete data, other publicly available data from past years, such as from the Toronto District School Board,11 Dufferin Peel Catholic School Board,12 and Halton Catholic District School Board13 all show students from various Asian backgrounds academically outperforming their white counterparts. Simply put, the OHRC’s claim that “people of European descent” are advantaged in Ontario’s education system is without convincing evidence. If the OHRC concludes that black students face systemic discrimination in Ontario’s education system because their academic performance is worse on average, it must also conclude that Asian students are unfairly and systemically advantaged in Ontario’s education system because their academic performance is better on average—a conclusion which makes no sense.

The OHRC cites two other reports, its “Compendium of Recommendations”14 and “What We Heard Report,”15 to support its assertion that there has long been, and continues to be, systemic discrimination against black students in Ontario’s education system. According to those reports, students have reported: hearing racial pejoratives from other students or from teachers, being threatened with racial violence from non-black students, being the victims of punitive discipline without thorough investigation, and witnessing other students using black face without reprimand. Other examples are given of students reporting being treated unfairly, sometimes as a result of their race.

Such incidents warrant condemnation, and efforts should be made to reduce them, but it is important to differentiate between systemic versus individual acts of racist discrimination. A student hurling racial insults at another student is an individual act of racism, not evidence of systemic discrimination. The OHRC defines “systemic discrimination” or “systemic barriers” as consisting “of attitudes, patterns of behaviour, policies or practices that are part of the social or administrative structures of an institution, sector or system.” The use of racial insults is unacceptable, but it is not part of the social or administrative structures of Ontario’s education system.

Indeed, the OHRC report gives no examples of systemic racial discrimination in the sense of the education system consisting of policies or structures that negatively discriminate against black students. None! In fact, where the OHRC gives examples of specific policies or structures that discriminate based on race, it is to give special help to black students. Two examples are the Centre of Excellence for Black Student Achievement at the Toronto District School Board, which prioritizes the needs and experiences of black students, and the Sankofa Centre of Excellence in the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board, which has similar goals.

The OHRC recommends 29 actions, many of them broken out into a long list of sub-actions to be undertaken variously by school boards, education faculties, teachers’ unions, the provincial government, and other organizations, on how to address anti-black racism in education. Summarizing this list of actions and sub-actions is beyond the scope of this analysis, but one clear and effective action to reduce racism in Ontario’s education system is notable in its absence from the OHRC list: increase school choice. If Ontario’s government-run education system is systemically racist as the OHRC claims, the obvious solution would be to give parents more choice and more access to alternatives to the government-run system. After all, if given access to other choices, parents would not send their children to schools where they will face systemic racial discrimination.

The OHRC has published an action plan for addressing systemic anti-black racism in education, but its action plan is flawed because it does not actually produce evidence of systemic anti-black racism. It presents examples of individual acts of racism against black students, which are undoubtedly bad, but this is not the same as actual policies or procedures that racially discriminate against black students or anyone else.

Moreover, the OHRC attempts to demonstrate through statistical inference and the historical injustice of slavery that black students face systemic discrimination in society and in education, but this is logically flawed. Disparities in outcomes do not imply discrimination, systemic or otherwise. Moreover, other minority groups faced historical state-sanctioned injustices in large numbers (the Chinese head tax and the internment of Japanese Canadians), but today the Canadian-born Chinese and Japanese, among those of other minority backgrounds, have higher average earnings than their white counterparts. Data from school boards across Ontario also show these groups academically outperforming white students on average, which is completely counter to the OHRC’s claim that students of European descent are unfairly advantaged at the expense of others in Ontario’s education system.

At bottom, the OHRC’s premise and conclusions are flawed.

Matthew Lau is a Senior Fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. A financial analyst by trade, his writing covers a wide range of subjects including fiscal policy, economic theory, government regulation, and Canadian politics. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree with a specialization in finance and economics from the University of Toronto, and is a CFA charterholder.

Who we are

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new education and public policy think tank that aims to renew a civil, common-sense approach to public discourse and public policy in Canada.

Our vision

A Canada where the sacrifices and successes of past generations are cherished and built upon; where citizens value each other for their character and merit; and where open inquiry and free expression are prized as the best path to a flourishing future for all.

Our mission

We champion reason, democracy, and civilization so that all can participate in a free, flourishing Canada.

Our theory of change: Canada’s idea culture is critical

Ideas—what people believe—come first in any change for ill or good. We will challenge ideas and policies where in error and buttress ideas anchored in reality and excellence.

Donations

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity, and all donations will receive a tax receipt. To maintain our independence, we do not seek nor will we accept government funding. Donations can be made at www.aristotlefoundation.org.

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy has internal policies to ensure research is empirical, scholarly, ethical, rigorous, honest, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge and the creation, application, and refinement of knowledge about public policy. Our staff, research fellows, and scholars develop their research in collaboration with the Aristotle Foundation’s staff and research director. Fact sheets, studies, and indices are all peer-reviewed. Subject to critical peer review, authors are responsible for their work and conclusions. The conclusions and views of scholars do not necessarily reflect those of the Board of Directors, donors, or staff.

Image credits: iStock

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER