Drawing a link between poverty and discrimination is common in Canadian policymaking. The federal government’s anti-racism strategy states that anti-black racism is a cause of high black poverty rates in Canada,1 and its anti-poverty strategy mentions racism as a reason why people from visible minority groups experience poverty. The federal anti-poverty strategy therefore proposes targeting funding towards minority groups: for example, community supports targeted at black Canadians and funding employment and skills training exclusively for Indigenous populations.2 Similarly, the Ontario government’s anti-racism plan also points to racism as a cause of black poverty,3 and its anti-poverty strategy also includes race-based funding, such as supports for “priority groups” including “racialized and Indigenous people.”4

But do race-based government anti-poverty programs and funding actually help those in poverty? Who benefits from such policies, and who do they fail to assist? This report presents the evidence on poverty in Canada, explores the efficacy of race-based policies, and examines the most effective way to lift Canadians out of poverty.

Looking at the data on those in poverty reveals how misguided race-based anti-poverty programs and funding are. To start, it is important to define “poverty” and in doing so to distinguish between absolute and relative poverty. When someone is living in absolute poverty, they lack the means to provide the basic necessities of life. As of 2019, fewer than three percent of people in Canada are poor in absolute terms.5 However, poverty reduction and anti-poverty strategies do not tend to target this group alone—they also focus on those considered poor relative to the rest of the population based on either income or the cost of living.

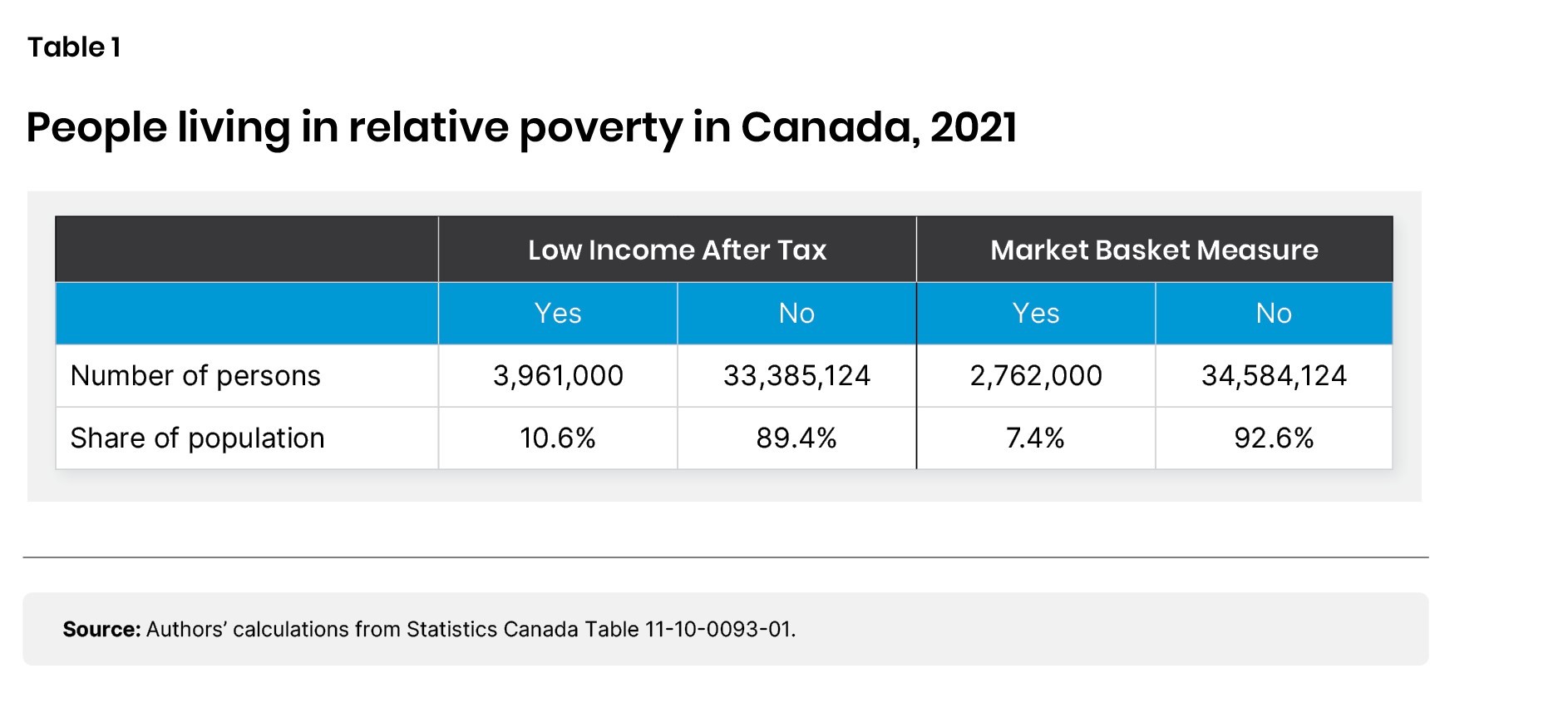

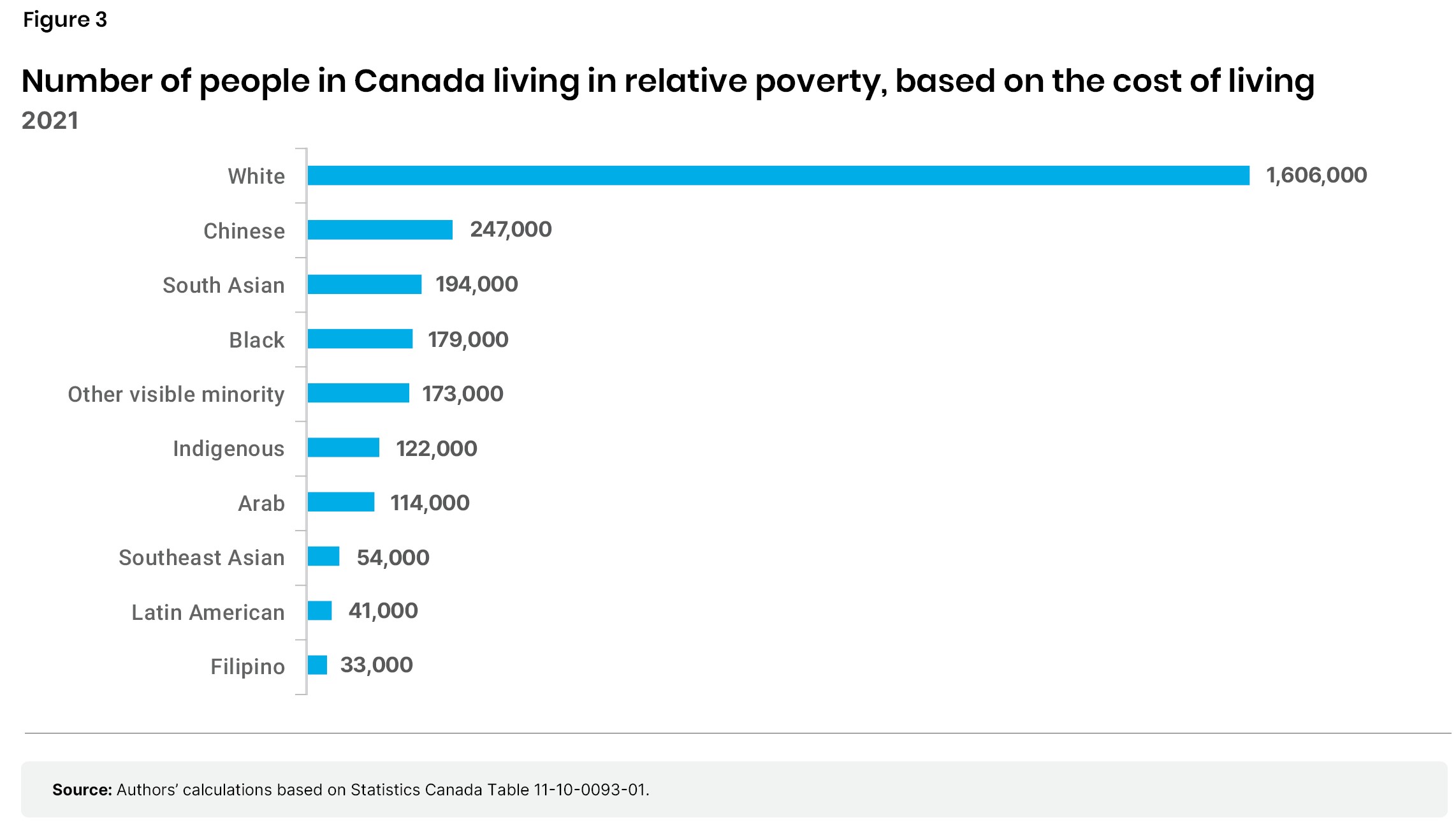

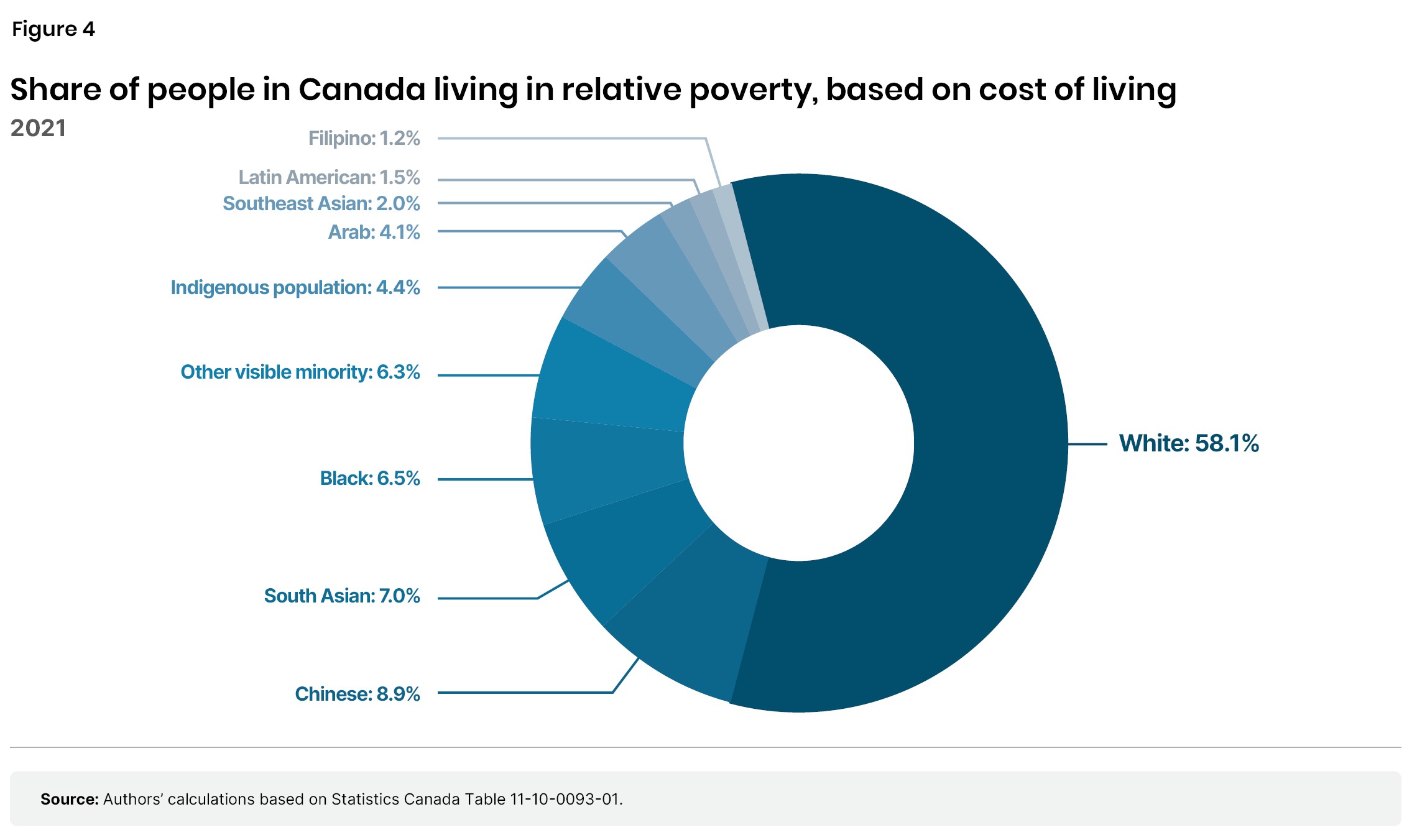

Statistics Canada uses two measures to gauge relative poverty in Canada. The “low income after tax” measure includes the group whose incomes are below 50 percent of the adjusted median household income—in other words, the home earns less than half of the average household’s income. About 10.6 percent of Canada’s total population (table 1) is in this group. Of the nearly 4 million people in Canada matching this definition of poverty, over 2.5 million (figure 1) or 64.4 percent (figure 2) are white—or, what Statistics Canada labels, “Not a visible minority nor Indigenous.” Statistics Canada also has an alternative “market basket measure” that estimates the poverty rate based on the cost of living.6 Under this approach, the number of people considered to be living in poverty drops considerably—to nearly 2.8 million, or 7.4 percent of the population. Of those, 1.6 million (figure 3) or just over 58 percent (figure 4) are white (“Not a visible minority nor Indigenous”). Quite simply, an anti-poverty policy that focuses on race excludes the majority of people who are living in poverty in Canada.

The problem is not limited to excluding the majority of the poor; it also ends up misdirecting resources to those who are not in poverty. Take, for example, the Ontario government’s “Racialized and Indigenous Supports for Entrepreneurs (RAISE) Grant Program,” that makes millions of dollars available “to help Indigenous, Black and other racialized entrepreneurs.”3 Using the low-income-after-tax measure, eligibility for this race-based funding would apply not only to 1.4 million low-income earners in Canada (the total low-income visible minority and Indigenous population) if they choose to be entrepreneurs but also to nearly 10.5 million minorities or Indigenous who are not low income, while excluding non-minority, non-Indigenous low-income earners. Put another way: this funding would be inaccessible to 64 percent of those who are low-income, and of those who do qualify for the funding based on race, only 11.9 percent are low-income. This is not a sensible way to design an anti-poverty program.

Race-based government programs do an inadequate job of targeting the poor, and thus aid only a small share of those most in need. For example, less than 15 percent of the Canadian population of African ancestry (i.e., black) are low-income; 11.5 percent of them are living in poverty according to the market basket measure (table 2). In other words, between 85.2 percent and 88.5 percent of black Canadians are not in poverty. Thus, as illustrated above, an anti-poverty program based on race but not financial need as its criterion will predominantly benefit those who are, in fact, not living in poverty.

In Canada, while some visible minority groups experience poverty in numbers disproportionate to the general population, it is also true that some visible minority groups are less likely to live in poverty. The groups least likely to be living in low income after tax in Canada are those with Filipino, South Asian, and Latin American ancestry (table 2). Those of Filipino descent are also, by far, the least likely to live in poverty as determined by the market basket measure.

Clearly, based on statistics alone, if the aim of race-based funding programs is to combat poverty, they miss their mark. However, more than data suggests that race-based programs will not combat poverty effectively. In 1970, noted economist George Stigler, who went on to win the Nobel Prize in 1982, published an article in the Journal of Law and Economics titled “Director’s Law of Public Income Redistribution.”7 As Stigler explained it, Director’s Law, named for University of Chicago professor Aaron Director, states that, “Public expenditures are made for the primary benefit of the middle classes, and financed with taxes which are borne in considerable part by the poor and rich.” According to Director’s Law, “Government has coercive power, which allows it to engage in acts (above all, the taking of resources) which could not be performed by voluntary agreement of the members of society. Any portion of society which can secure control of the state’s machinery will employ the machinery to improve its own position.”

The simple explanation of Director’s Law is that, in general, government spending will direct funding towards the large middle class, but it will be at the expense of those at the poor and the rich ends of the scale. The poor do not have the political power to fight the state to stop it doing so, and the very rich have the most per-capita resources for the state to take away. Consequently, unless government anti-poverty spending is tied to income (or another quantifiable measure of poverty), it will disproportionately benefit those who are not in poverty.

In a 1990 discussion of welfare programs that are ostensibly designed to reduce inequality, Thomas Sowell explained, “The crucial thing is, when you try to create this equality, you don’t create the equality, you create something else. I’ve been doing studies now for 20 years of programs designed to increase equality. They increase inequality. Because even when the programs are designed for disadvantaged groups, they help the affluent members of disadvantaged groups while the lower members of those groups fall further behind than ever before.”8

To use a modern Canadian example: the federal government requires its departments and agencies to have at least five percent of the total value of their contracts, if not currently then by 2025, held by “Indigenous businesses.”9 But as was uncovered in 2024 during the ArriveCan scandal, a single two-person firm received more than $200 million in federal contracts since 2015 by bidding on tenders set aside for Indigenous businesses and then subcontracting that work out to other businesses.10 “Federal procurement has become gamed by empty-shell companies—including ones specifically created to arbitrage affirmative action policies—who’ve stripped out significant margins for themselves and then passed off the work to others,” as The Hub’s Sean Speer put it.11

There are other unintended consequences of race-based procurement, also known as affirmative action. Affirmative action requires that more bureaucracy be involved in procurement-making decisions. Worse, the restrictive criteria of affirmative action all but ensures that government will overpay for goods and services, because the focus is no longer on getting the best value for taxpayers’ dollars (as amply demonstrated in the ArriveCan debacle). Taxpayers lose—including many who are poor.

Systemic racism is not the cause of poverty in Canada. This is apparent when contrasting the aforementioned findings with the federal government’s definition of systemic racism: “patterns of behaviour, policies or practices that are part of the social or administrative structures of an organization, and which create or perpetuate a position of relative disadvantage for racialized persons.”12 The data presented earlier show that some minority groups are only as likely, and some even less likely, to be in poverty than the white population. Moreover, this evidence is reinforced by recent research that finds:

If not systemic discrimination, what are the actual causes of poverty? There are many, in what may be an immeasurable confluence of factors. To borrow from economist Per Bylund, this is the wrong question, as poverty is humanity’s default, or starting, position. The better questions are how can we avoid or climb out of poverty? What leads to prosperity? The short answer, as it relates to poverty in Canada today, is a simple three-step recipe called the “success sequence”: finish high school, work full time, and marry before having children.14 In the United States, the most recent research finds 97 percent of Millennials who do this—in this order—are not in poverty by their thirties. In Canada, using 2015 data, economist Christopher Sarlo found that while 5.5 percent of households lack enough income for basic necessities, this is the experience of only 0.9 percent of two-parent families whose reference person is employed full-time and has graduated from high school.15 In other words, in Canada, 99 percent of adults who have followed the success sequence are not living in absolute poverty today. Clearly, poverty in Canada is not a matter of one’s racial background.

Many government anti-poverty and anti-racism programs and strategies draw a link between poverty and racism, which is misguided for at least three reasons. First, there is no causal relationship between race and poverty in Canada. Second, even if race-based funding is targeted towards groups that are more likely to be in low-income situations, the beneficiaries are likely to be the top members of those groups, while those in need are left behind. And third, the majority of Canadians living in poverty are neither visible minorities nor Indigenous, and thus cannot receive race-based resources. Such programs and funding exclude most Canadians in poverty, including those whose taxes pay for those programs.

If the goal of public policy is to reduce poverty, policymakers should seek to address the root issues by strengthening, or minimizing interference with, the “success sequence.” And clearly, anti-poverty government programs and funding should assist those in poverty, regardless of race.

In summary, poverty rates in Canada are low, not well accounted for by explanations of systemic racial discrimination, and race-based anti-poverty programs and funds tend to be ineffective, at best, for addressing the needs of those who are truly living in destitution.

Matthew Lau is a Senior Fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. A financial analyst by trade, his writing covers a wide range of subjects including fiscal policy, economic theory, government regulation, and Canadian politics. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree with a specialization in finance and economics from the University of Toronto, and is a CFA charterholder.

David Hunt is Research Director at the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. David has published over a dozen peer-reviewed studies, written dozens of public commentaries, given dozens of speeches, and has been widely interviewed by media over the past decade. His work has been presented at various levels of government, appeared in all Canada’s major media, and used as evidence in court. David holds a Master of Public Policy from Simon Fraser University and a Bachelor of Business Administration (with distinction) from the Melville School of Business at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, where he was the Dean’s Medal recipient.

Who we are

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new education and public policy think tank that aims to renew a civil, common-sense approach to public discourse and public policy in Canada.

Our vision

A Canada where the sacrifices and successes of past generations are cherished and built upon; where citizens value each other for their character and merit; and where open inquiry and free expression are prized as the best path to a flourishing future for all.

Our mission

We champion reason, democracy, and civilization so that all can participate in a free, flourishing Canada.

Our theory of change: Canada’s idea culture is critical

Ideas—what people believe—come first in any change for ill or good. We will challenge ideas and policies where in error and buttress ideas anchored in reality and excellence.

Donations

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity and all donations will receive a tax receipt. To maintain our independence, we do not seek nor will we accept government funding. Donations can be made at www.aristotlefoundation.org.

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy has internal policies to ensure research is empirical, scholarly, ethical, rigorous, honest, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge and the creation, application, and refinement of knowledge about public policy. Our staff, research fellows, and scholars develop their research in collaboration with the Aristotle Foundation’s staff and research director. Fact sheets, studies, and indices are all peer-reviewed. Subject to critical peer review, authors are responsible for their work and conclusions. The conclusions and views of scholars do not necessarily reflect those of the Board of Directors, donors, or staff.

Image credits: iStock

The logo and text are signs that each alone and in combination are being used as unregistered trademarks owned by the Aristotle Foundation. All rights reserved.

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity. Our charitable number is: 78832 1107 RR0001.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER