In the recent federal election, a plethora of commentary arose vis-à-vis the possibility of Western separation should the federal Liberal party re-enter Parliament with a fourth term. In early April, Preston Manning, founder of the Reform Party, wrote a partisan column asserting that the re-election of a Liberal government under its new leader, Prime Minister Mark Carney, would result in a threat to national unity given frustrations in Western Canada.

Manning did not endorse separation. He was clear that he thought it a real possibility, arguing that “bottom-up support for Western secession—another one of those populist movements that central Canada has never anticipated or understood—” had the potential to spread to BC and Manitoba from where it is “currently centered,” in Alberta and Saskatchewan.1 In response, among others, several columnists and politicians took the former Opposition leader to task.

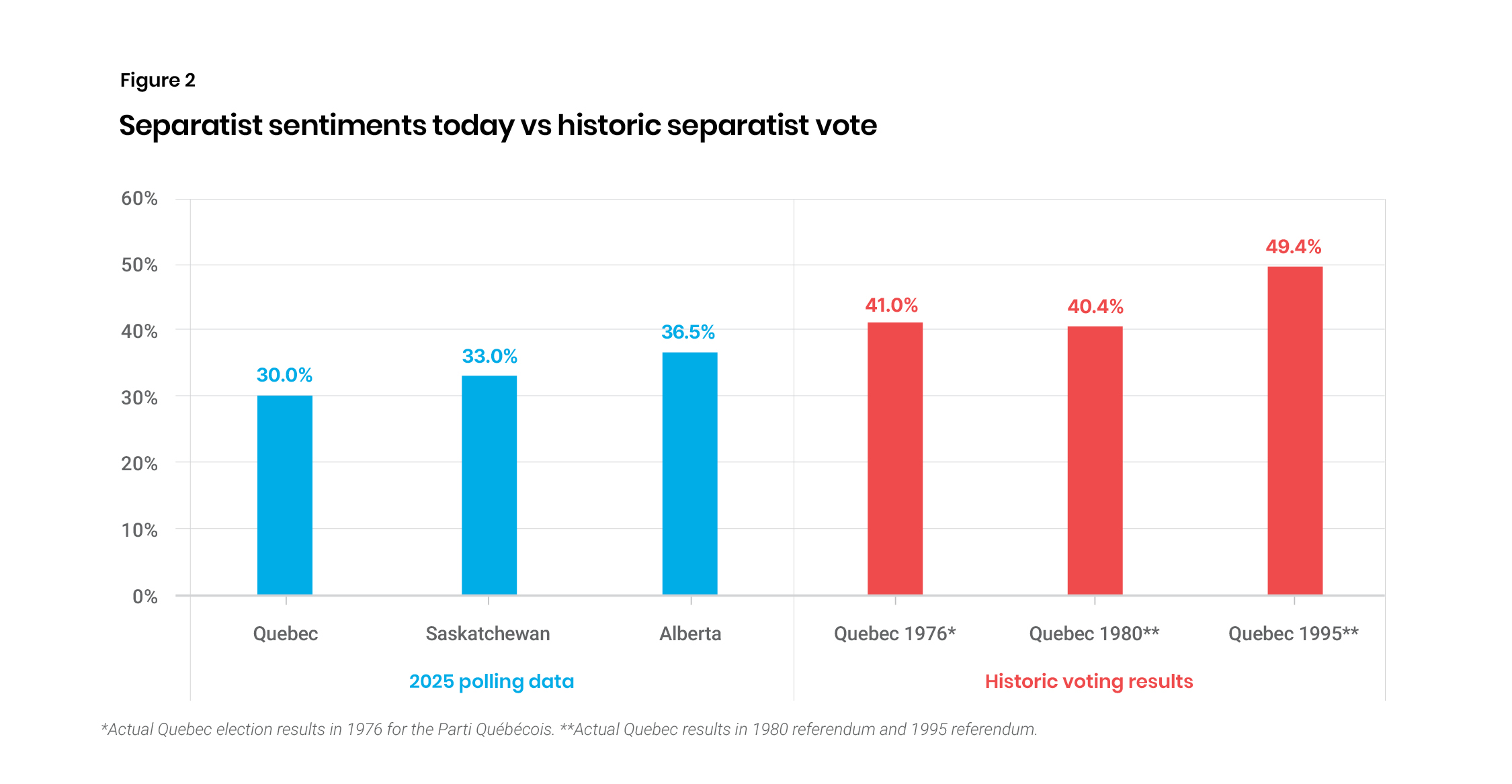

Western separatist sentiment should not be underestimated. In at least two provinces, support for separation exceeds current Quebec support for separation (though the range from low to high should be noted) and is nearing percentages achieved in the 1976 election of the Parti Québécois and support for separatism in the 1980 referendum.

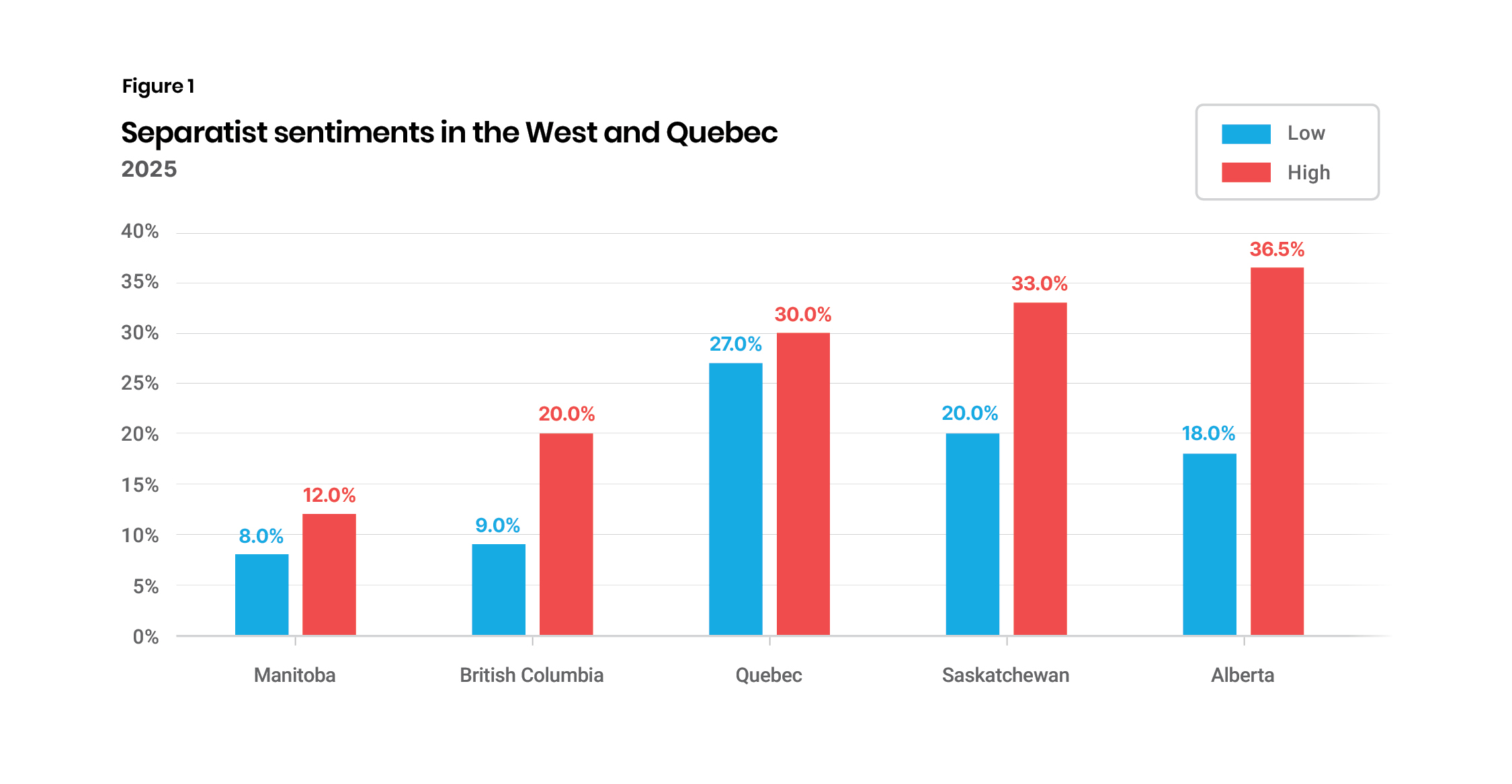

Mid-election polling data from the Angus Reid Institute found that between 25 percent and 30 percent of Albertans and between 20 percent and 33 percent of those in Saskatchewan favoured becoming an independent country (if the Liberal government was re-elected). In BC, support for separatism ranged from 9 percent to 17 percent, while in Manitoba, the range was 8 percent to 12 percent.8

Innovative Research found that between 18 percent (pre-election) and 34 percent of Albertans (post-election) would “probably” or “definitely” vote for separation. In BC, support ranged from 14 percent to 17 percent. On the Prairies (Manitoba and Saskatchewan combined) the figures were 18 percent pre-election and 13 percent post-election.9 Leger found that the range of Albertans favouring independence was between 29 percent (if Alberta alone was independent) and 34 percent (if in conjunction with other Western provinces).10 Mainstreet Research found that 36.5 percent of Albertans—the highest poll result—would “somewhat” or “strongly support” an independent Alberta on its own or with other Western provinces.11 In late May, Janet Brown found that 30 percent of Albertans somewhat or strongly favoured separation.12

Recent polls from the various polling firms place Quebec support for separation between 27 percent and 30 percent.13

Sources: Angus Reid Institute, Innovative Research Group, Leger, Mainstreet Research.

With Western support for separation as high as 33 percent (Saskatchewan) and 36.5 percent (Alberta), such responses mirror Quebec. Between a fifth (British Columbia) and a third or more (Saskatchewan and Alberta respectively) of respondents would consider separation. Such support might better be seen as a potential floor and not necessarily a ceiling.

A comparison of Western separatist sentiment with historic-Quebec votes for separation is also instructive (Figure 2). The 1976 election of the separatist Parti Quebecois in Quebec occurred with just over 41 percent of the vote.14 In the 1980 Quebec referendum on separation, “only” 40 percent voted for sovereignty association with Canada, a form of separation loosely defined.15 In 1995, the vote for separation was much closer with 49.4 percent voting for separation/sovereignty association.16

In discussions over Western separatist sentiment, grievances combined with charismatic figures—such as then Parti Quebecois leader René Levesque (later Quebec premier as of 1976) and Lucien Bouchard, founder of the Bloc Quebecois—played a significant role in fanning sparks of discontent into separatist flames. It is a mistake to assert that same dynamic is absent or could not exist in Western Canada.

Sources: Angus Reid Institute, Élections Québec, Innovative Research Group, Leger, Mainstreet Research.

Another element to ponder in analyzing whether Western separatist sentiment should be taken seriously is the impact that Quebec’s ongoing political and economic demands have on Canada and on public opinion in the West.

It is instructive to recall that British Columbians opposed a package of constitutional amendments, the Charlottetown Accord, in a 1992 referendum in greater proportion (68.3%) than did Albertans (60.2%)17 or Quebecois (56.7%).18 Part of the opposition in British Columbia and in other provinces was driven by proposals for special status for Quebec. As one academic noted in a post-mortem on the Charlottetown Accord referendum, “Citizens in provinces outside of Quebec resented being told that a deal had to be reached or Quebec would separate and the Canadian economy would be destabilized…. The public residing outside of Quebec also questioned the Yes side’s argument that the deal was necessary to redress Quebec’s grievances.”19

This particular issue, special status for Quebec, has not been headline news in recent years. However, it would be a mistake to assume that any existing or new policies seen as uniquely favourable to Quebec would not exacerbate separatist sentiment in Western Canada. An example is what appears to be a potential Quebec veto on cross-country pipelines offered up by Prime Minister Mark Carney. In February, the prime minister said he favours national projects including pipelines if a consensus exists.20 However, both the Quebec premier, Francois Legault,21 and the leader of the separatist Bloc Quebecois, Yves-François Blanchet, have stated they oppose more oil development, including oil pipelines.22 Given the April 28, 2025 election results—the governing Liberals are three seats short of a majority, and the Bloc Québécois hold 2223—it is conceivable that demands from a Quebec-centric party will increase, and with it, potential opposition to Quebec-centered demands in other parts of Canada (and not just from the West), as occurred in the 1980s and 1990s.

If the polling is accurate, separatist sentiment is highest in Canada’s wealthiest province, Alberta. Unlike Quebec voters who, in separatist referendums, must consider how to finance provincial government services absent federal transfers from the rest of Canada, Albertans might be more easily tempted to cast a vote for separation on the calculation that provincial wealth now and in the future would allow their province and their own finances to continue with little downside and potentially a fiscal upside. Some Canadians in other Western provinces may also make that calculation, even if their province has not been a net contributor to Confederation. Downplaying or dismissing Western Canadian sentiment at this juncture would be in error.

Mark Milke, PhD, is the founder and president of the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. Mark is a public policy analyst and author with six books, over 70 studies, and more than 1,000 columns published in the last 25 years. His policy work has been published by numerous think tanks in Canada and internationally. He is the editor of the Aristotle Foundation’s first book, The 1867 Project: Why Canada Should Be Cherished–Not Cancelled. In 2022, Mark was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Medal in recognition of his service to the province of Alberta.

Ven Venkatachalam, PhD, is the senior economist with the Aristotle Foundation and empirically anchors our work in data and statistics. He is an economic and social researcher with expertise in a number of areas including economic and fiscal policy, international relations, trade, energy, governance, education, immigration, tourism, and NGO matters. He has consulted for governments, NGOs, and private sector organizations across Asia, Europe, Canada, and the United States.

Who we are

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new education and public policy think tank that aims to renew a civil, common-sense approach to public discourse and public policy in Canada.

Our vision

A Canada where the sacrifices and successes of past generations are cherished and built upon; where citizens value each other for their character and merit; and where open inquiry and free expression are prized as the best path to a flourishing future for all.

Our mission

We champion reason, democracy, and civilization so that all can participate in a free, flourishing Canada.

Our theory of change: Canada’s idea culture is critical

Ideas—what people believe—come first in any change for ill or good. We will challenge ideas and policies where in error and buttress ideas anchored in reality and excellence.

Donations

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity, and all donations will receive a tax receipt. To maintain our independence, we do not seek nor will we accept government funding. Donations can be made at www.aristotlefoundation.org.

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy has internal policies to ensure research is empirical, scholarly, ethical, rigorous, honest, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge and the creation, application, and refinement of knowledge about public policy. Our staff, research fellows, and scholars develop their research in collaboration with the Aristotle Foundation’s staff and research director. Fact sheets, studies, and indices are all peer-reviewed. Subject to critical peer review, authors are responsible for their work and conclusions. The conclusions and views of scholars do not necessarily reflect those of the Board of Directors, donors, or staff.

Image credits: iStock

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER