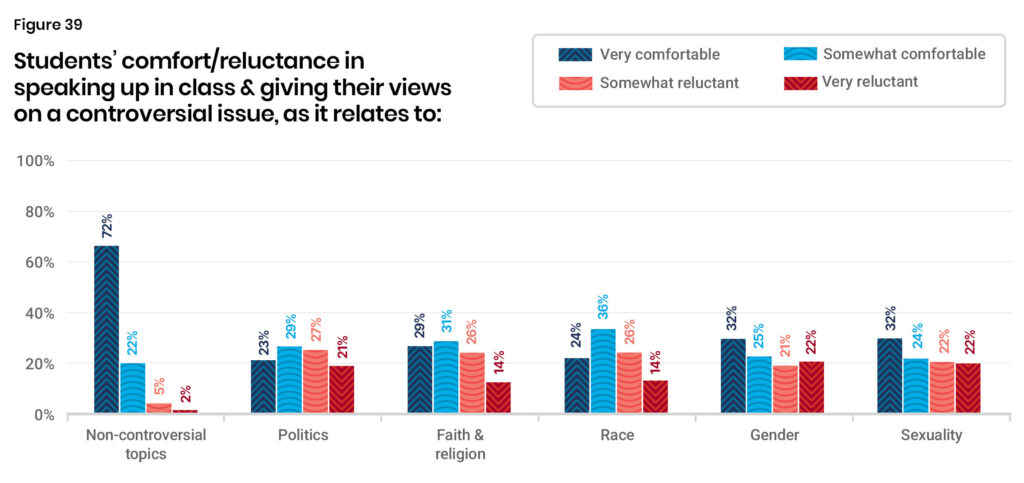

To what extent are students willing to express their views in a university classroom? On non-controversial issues, 93.4 percent of students are comfortable sharing their perspective. But what happens when a controversial issue is raised?

We completed a survey of 760 students from universities across Canada, asking participants to gauge their comfort or reluctance in speaking up and giving their views on five potentially controversial issues: politics, religion, race, gender, and sexual orientation.

Of the five controversial areas, students are most reluctant to share their views on a potentially controversial political issue—half are hesitant. This is linked to the fact that just shy of half of all university students in our study perceive that they experience bad or unfair treatment at least once a year because of their political views. Students hold a wide range of political views, but three political positions are particularly informative.

The disparity in perceived freedom to express one’s views among students holding differing views is not limited to political views but was also observed in other areas such as religion. Despite religious students outnumbering non-religious students two to one, it is the non-religious who are considerably more comfortable in a university classroom discussing controversial issues about faith and religion. The data reveals particular concerns around the experience of Catholic, Muslim, and Jewish students, with the latter reporting considerable mistreatment in their university experience. Jewish students participating in our study are four times more likely than the average student to be “very reluctant” to speak up and share their views on religion in class discussions. This fear of expressing their viewpoints correlates to a concerning outcome in the study, whereby 15 percent of Jewish students reported experiencing daily abuse on campus for being Jewish, and 84 percent reported experiencing antisemitism at university at least once a year. By contrast, 90 percent of agnostics, 86.6 percent of atheists, and 75.5 percent of students who elected not to disclose their religious affiliation reported never being treated badly or unfairly, as a university student, because of their religious views. In other words, an agnostic or atheist student from our study population is six times more likely than a Jewish student to report never being treated badly or unfairly for their views on religion. Not a single agnostic, atheist, or “prefer not to say” participant in our study reported daily mistreatment.

Unlike the topics of religion and politics where material variations on freedom of expression are obvious, the results on the topic of race are less clear. On one hand, nearly 48 percent of students experience racial discrimination at least occasionally. As such, racism clearly continues to be an issue on campus. Yet, less than 2 percent of students in our study reported experiencing ill treatment because of their race daily—and the rate rises merely 0.6 percentage points, when excluding white students. In other words, the data do not reveal clear relationships. After analysis, a plausible explanation is that, where racism occurs, it is possibly by and towards individuals of sub-cohorts within cohorts (e.g. Ulster versus Irish; Punjabi versus Pakistani; Palestinian versus Israeli, etc.). The data suggest that racial discrimination is infrequently reported as occurring within the classroom compared to other parts of campus. Finally, it is worth noting that the data reveal that those least likely to experience racism are also some of the least likely to feel free to talk about race (i.e., white students); the data suggest that their views on race are generally unwelcome.

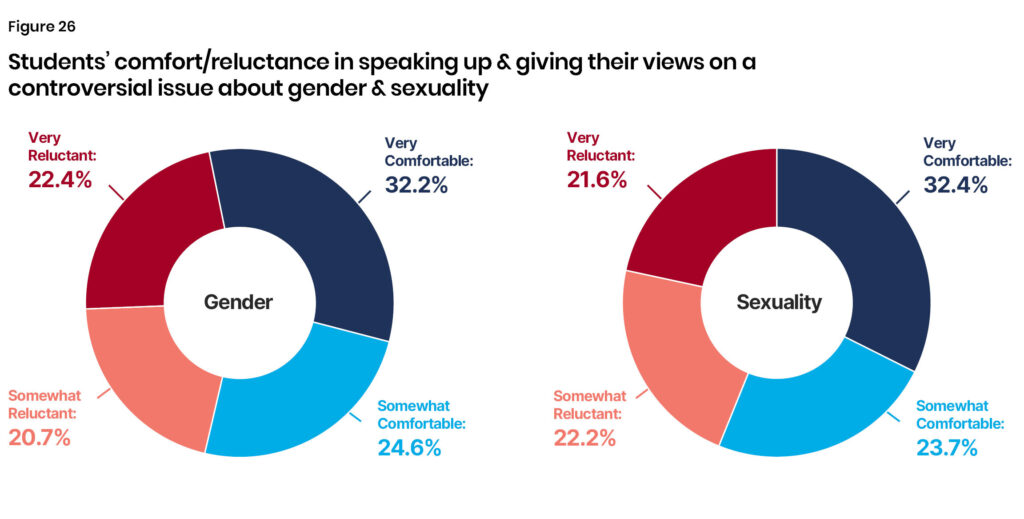

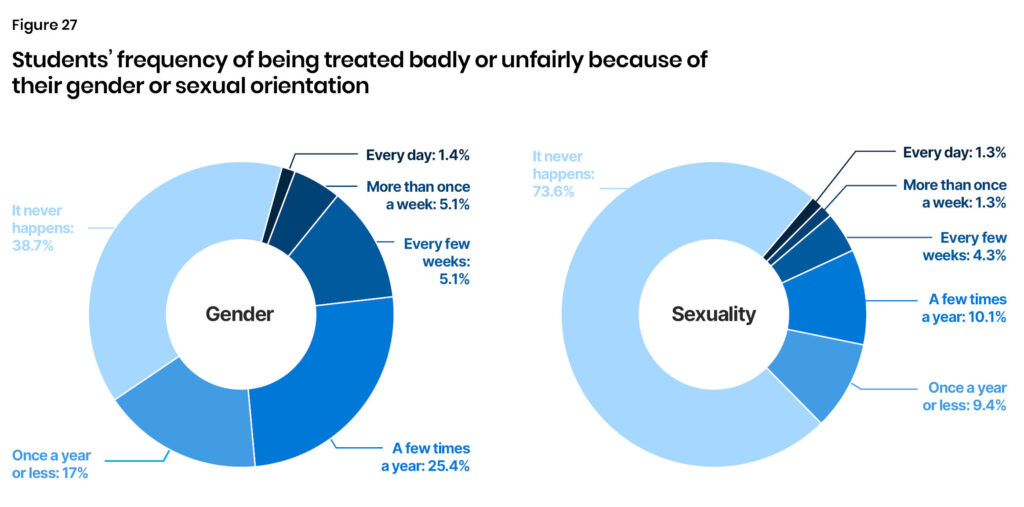

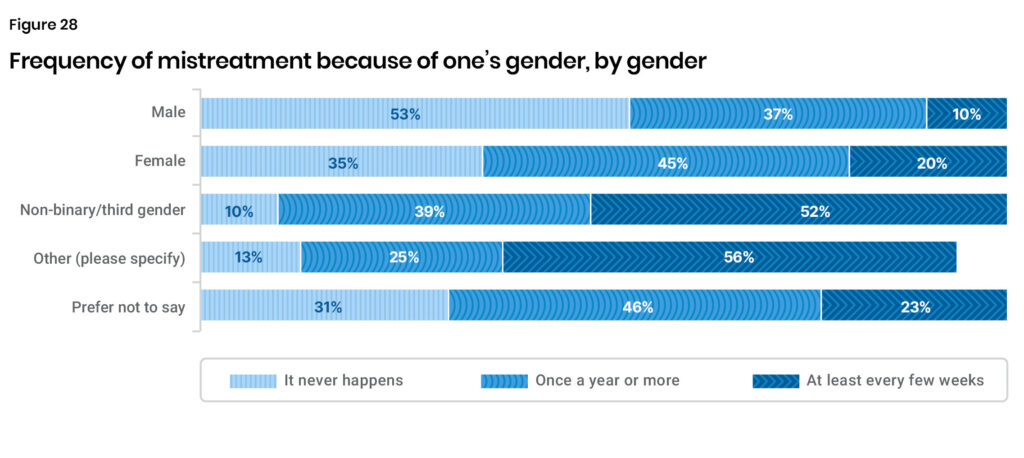

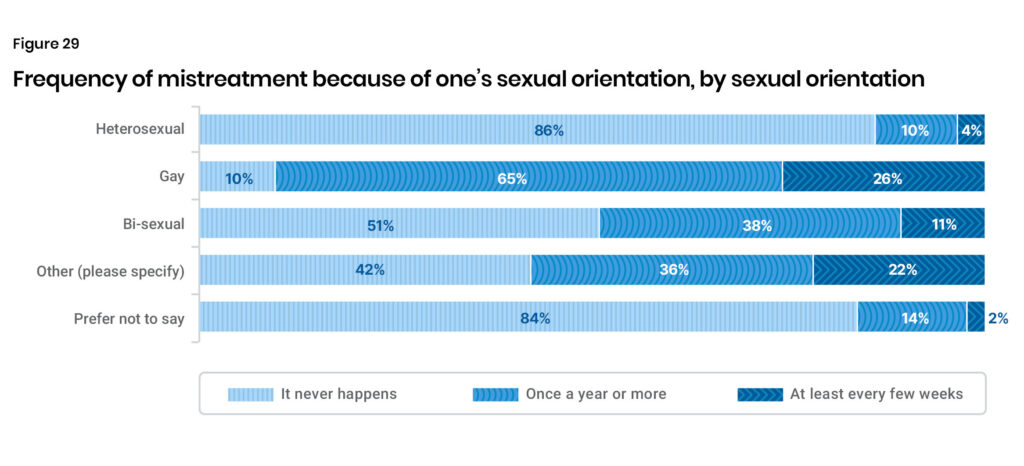

Gender and sexuality are the most polarizing topics. On one end, they have the largest share of respondents who expressed that they were “very comfortable” (32%) sharing their honest views on a controversial matter in class; yet, gender and sexuality also have the largest share who expressed that they were “very reluctant” (22%). Like race, the gender and sexuality findings are mixed. Those who rarely experience any mistreatment for their gender or sexual orientation—heterosexual males—are, by far, the least likely to feel at liberty to share their views on those issues. Whereas, despite experiencing more frequent mistreatment—90 percent of students who identify as gay, non-binary, or third gender reported experiencing poor or unfair treatment because of their gender at least once a year—gender-nonconforming and non-heterosexual students are the most comfortable sharing their views on controversial gender and sexuality issues in class.

In conclusion, the data from our study demonstrate that students who self-identify with the following five characteristics are the most comfortable sharing their views on controversial topics at Canadian universities: liberal, secular, racialized, homosexual, and gender-nonconforming. Students who do not identify with these characteristics express much higher levels of concern in sharing their views on controversial topics in the classroom for fear of being downgraded in their assessments, shamed by instructors as holding inappropriate beliefs, or facing other reprisals.

The data evidence that the state of affairs at Canadian universities is falling short of the ideal of freedom of expression on campus. Inescapable from our study is the recognition that classroom discussions on controversial topics on university campuses fail to reflect the actual cross-section of opinions of students in the classroom, as students who perceive their beliefs as inimical to their professors’ opinions remain silent out of fear of negative consequences of honest expression of their beliefs. If the open and free exchange of ideas leads to greater understanding between, and tolerance amongst, individuals with differing viewpoints and lived experiences, then the study data make it clear that significant work remains to be done on Canadian university campuses in creating safe spaces that encourage more open expression to reach this ideal.

Universities, by design, are places of inquiry, discovery, and debate. One’s preconceptions will be challenged, and alternative perspectives will be presented. By expressing our views on a difficult subject and listening to the rebuttals and responses, we more effectively determine whether our current positions need to be modified or buttressed. By observing the weakness of our positions exposed in open debate, we recognize the comparative strength of alternative viewpoints and, potentially, where our current opinions reflect a lack of understanding of other positions. This is the nature of research, teaching, and learning. As such, providing an environment in which free expression and open inquiry are observed in the classroom has long been seen as the ideal in higher education. How well, though, are we delivering on this ideal in Canada? To what extent is free expression actually nurtured on campus in general, and, more specifically, in the classroom?

Examining five potentially controversial topics—politics, religion, race, gender, and sexual orientation—we surveyed 760 university students across Canada to assess and understand how comfortable or reluctant they are sharing their perspectives on these topics.

This section introduces the purpose of our research; the second section presents our method; the third and longest section explores the survey results by topic; the fourth section analyzes the results; and the final section reflects on three key themes that emerge from the data.

Freedom of expression is one of the fundamental rights guaranteed to Canadians by Section 2(b) of The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. According to the Government of Canada, “the protection of freedom of expression is premised upon fundamental principles and values that promote the search for and attainment of truth, participation in social and political decision-making and the opportunity for individual self-fulfillment through expression.”i On university campuses, the right to freedom of expression most often manifests itself in the context of students’ rights to engage in public protest on controversial social and political issues. Campus protests have gained particular attention over the past two years with pro-Palestinian students protesting Israeli actions in Gaza.

While freedom of expression in relation to public protests on campus is undoubtedly an important issue, public protests are rare events in the lives of most students. Our focus in conducting the study was on ascertaining the quality of freedom of expression enjoyed on a daily basis, namely the degree to which university students on Canadian campuses feel free to engage in open and honest dialogue in the classroom on controversial issues without fear of reprisal. Universities universally aspire to encourage open and honest debate as a critical tool on the path to enlightenment, tolerance, and mutual understanding. This includes opinions that are both popular and unpopular at any particular time. If only popular opinions are welcome in the classroom, our classrooms quickly become echo-chambers, and the opportunity for meaningful debate and dialogue is lost. A false perception of consensus is secured at the cost of honest inquiry, and the students holding the unpopular opinions simply disengage from the conversation without truly assessing the underpinnings of their beliefs. By expressing one’s unpopular beliefs in the classroom and then having those beliefs challenged respectfully with countervailing points of view, we learn where our current belief structures require modification. Without dissenting views expressed, the opportunity for moderation and evolution of our opinions is lost.

Universities have sought for years to create “safe spaces” in which marginalized students feel secure and supported, free from discrimination and harm. These are undoubtedly important initiatives. However, universities do little to promote or monitor the quality of free expression that exists inside of the classroom setting for what they classify as “non-marginalized students.” This belies a presumption that classrooms organically support open inquiry and the exchange of ideas, and that non-marginalized students enjoy sufficient freedom to express their own opinions. Is this presumption valid? Anecdotal stories have circulated widely for years claiming that university students are frequently unwilling to share personal opinions in the classroom on controversial matters that they believe will be unpopular. This is especially likely when a student’s particular opinion contradicts the opinion of a professor, for fear of being ridiculed, shunned, and even downgraded in assessments. Our study specifically set out to determine the degree to which these anecdotes reflect the experience of students on Canadian university campuses today. Moreover, our study was designed to establish which particular demographic groups on Canadian university campuses feel more or less free to express their opinions in class discussions.

There are a vast number of scholarly sources written on the state of free speech on Canadian campuses. Included in these efforts was an annual report from the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms, which published the Campus Freedom Index annually from 2011 to 2021. However, these analyses have largely been focused on the experience and policies of universities in terms of protecting freedom of speech writ large, specifically in the context of protecting (or failing to protect) the public presentation of controversial opinions of visiting guest speakers on campus, student protests on campus, and the spoken opinions and writings of faculty. The Campus Freedom Index was specifically based on analysis of documents and anecdotal evaluation of specific instances whereby the university stepped in to either protect or restrict free speech.

While the protection of freedom of expression in the public forum at universities is important, our primary interest in initiating, designing, and executing the study was the daily lived experience of students on Canadian university campuses. We will leave to these other sources the analysis of policies and procedures that exist in central administrative offices on campus; we seek to understand what is actually happening in the individual classrooms. Policies and procedures are simply words written on paper if they fail to create an environment that fosters the free and open exchange of ideas in the classroom setting. No analysis of written records can provide illumination on the daily experiences of students; only the students themselves can report as to their willingness to express opinions on controversial topics.

A survey was created based upon (and with permission from) the Heterodox Academy’s Campus Expression survey. Recruitment was conducted with a rolling sample procedure. Thirty-four universities (see Appendix A) from across Canada were enrolled in the study, 1,174 students started the survey, and 760 respondents completed the survey in its entirety. Respondents were not required to complete every question; thus, the number of respondents (n) varies by question—typically ranging from 757 to 843. For more details on the methodology, including limitations, please see Appendix B.

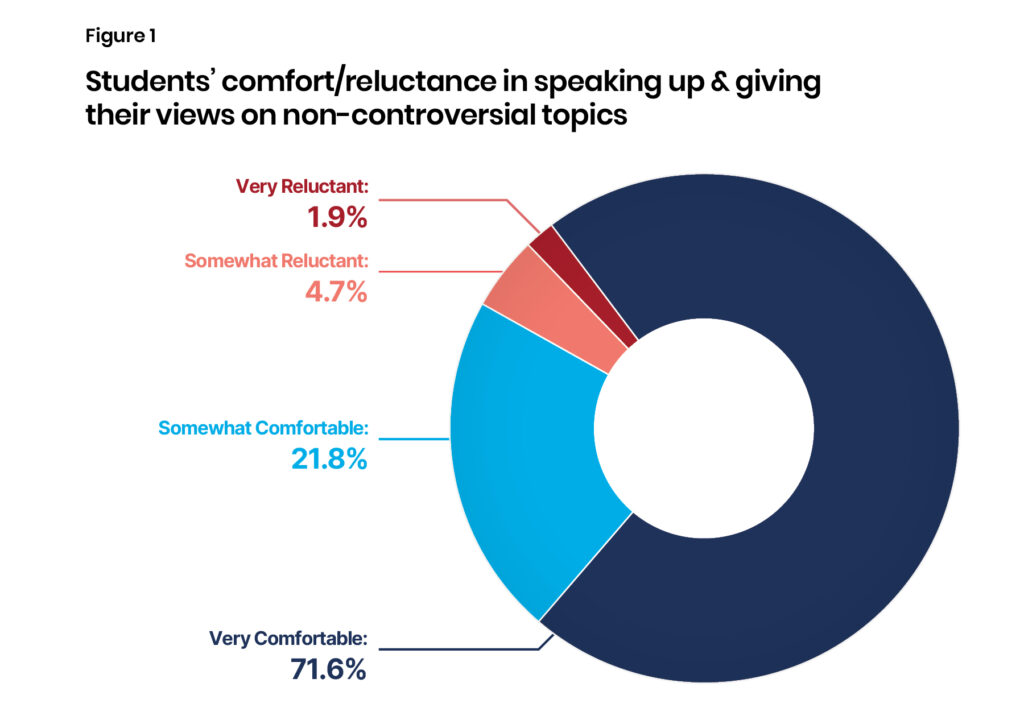

To assess the state of free speech on campus and allow for meaningful comparisons, we start with a baseline: Are Canadian university students comfortable speaking up in class on non-controversial issues? Figure 1 shows that 93.4 percent of university students are comfortable giving their views. (See Figure C1 in Appendix C for a detailed breakdown.)

As such, we observe that university students are generally willing to speak up in class when the subject matter of the discussion is non-controversial. Only a small minority of students are inherently nervous about expressing their thoughts to their classmates and instructors in the form of an open classroom discussion.

But what about when the topic of discussion engages issues that the students perceive as controversial? This section examines university students’ willingness to share their views on five potentially controversial topics—in order: politics, religion, race, gender, and sexual orientation.

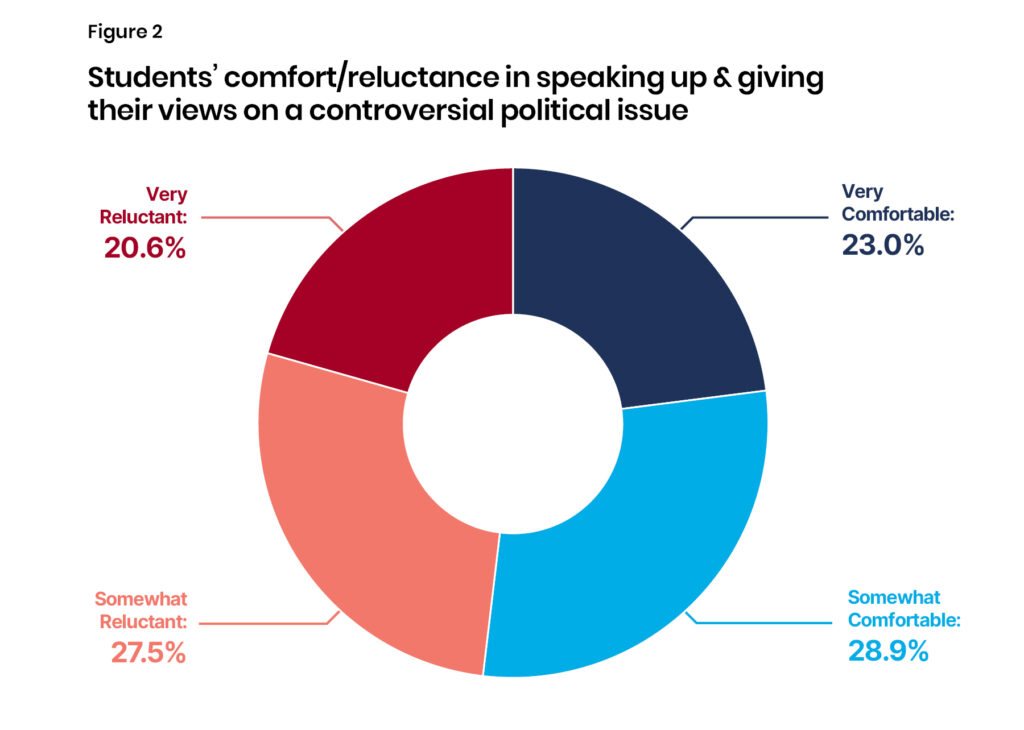

When covering a controversial political issue in the classroom, comfort levels drop precipitously. University students are about three times less likely to be “very comfortable” and 10 times more likely to be “very reluctant” in sharing their views on a controversial political issue, compared to non-controversial issues. As Figure 2 shows, the typical Canadian university classroom is roughly quartered on controversial political issues between those reporting to be very comfortable (22.3%), somewhat comfortable (28.9%), somewhat reluctant (28.4%), and very reluctant (20.4%) to speak up and give one’s views. Approximately half of students are comfortable and half are reluctant to share their perspectives on controversial political issues, making politics the most contentious of the five controversial topics (in terms of willingness to share one’s views).

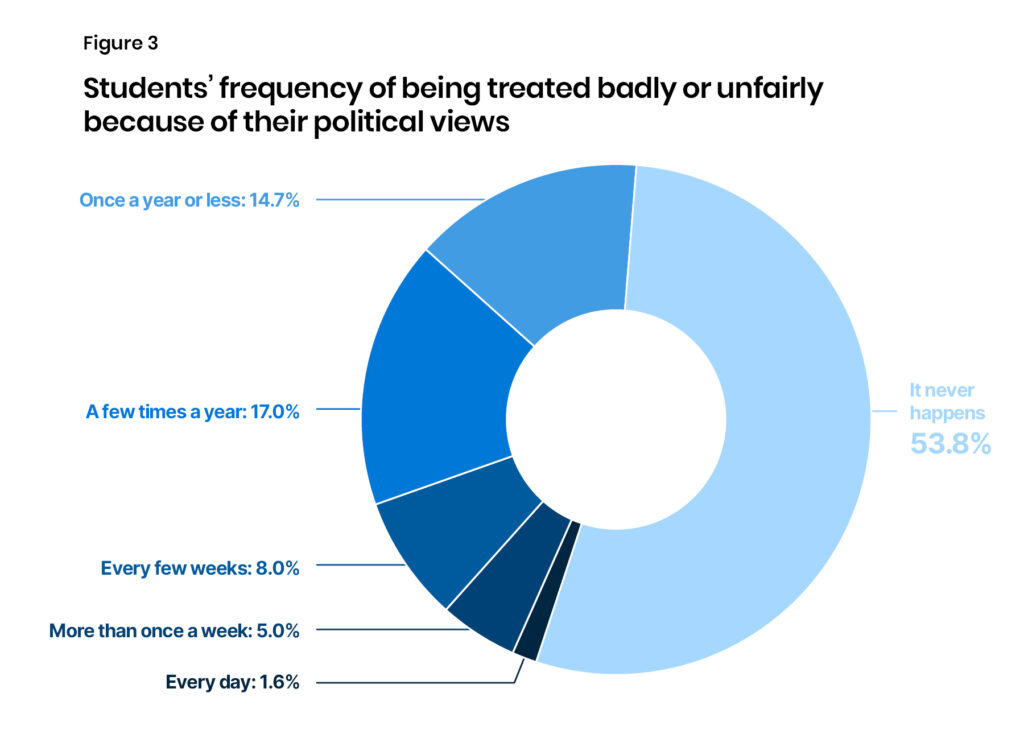

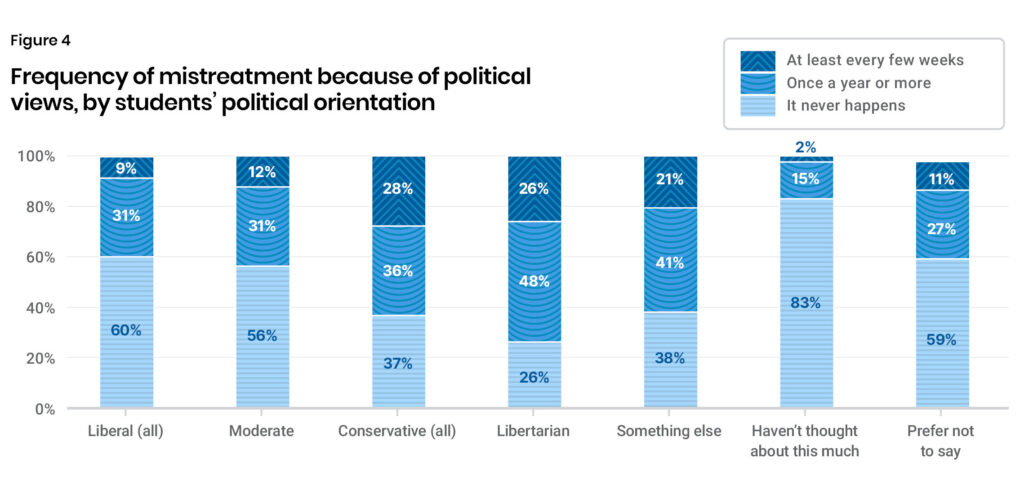

Is this reluctance to share one’s political views correlated with mistreatment for those views? It appears so. Only half (51.2%) of university students feel comfortable sharing their views on controversial political issues, and 53.8 percent report never being treated badly or unfairly because of their political views (Figure 3): almost a perfect match. Figure 4 breaks this down by self-reported affiliation, revealing an imbalance in the direction of mistreatment. Using regression analysis, we find a significant positive correlation between student alignment with left-leaning political views and willingness to express viewpoints on political issues (r = 0.2, p < 0.001). Furthermore, students who reported having right-leaning political views were significantly more likely to report feeling poorly treated (r = -0.27, p = < 0.001). In contrast, there were no significant correlations among these variables regarding non-controversial topics. Although the variance is small, the findings suggest that students who lean politically rightward are significantly more likely to be reluctant in expressing their viewpoints in class and to report feeling treated poorly.

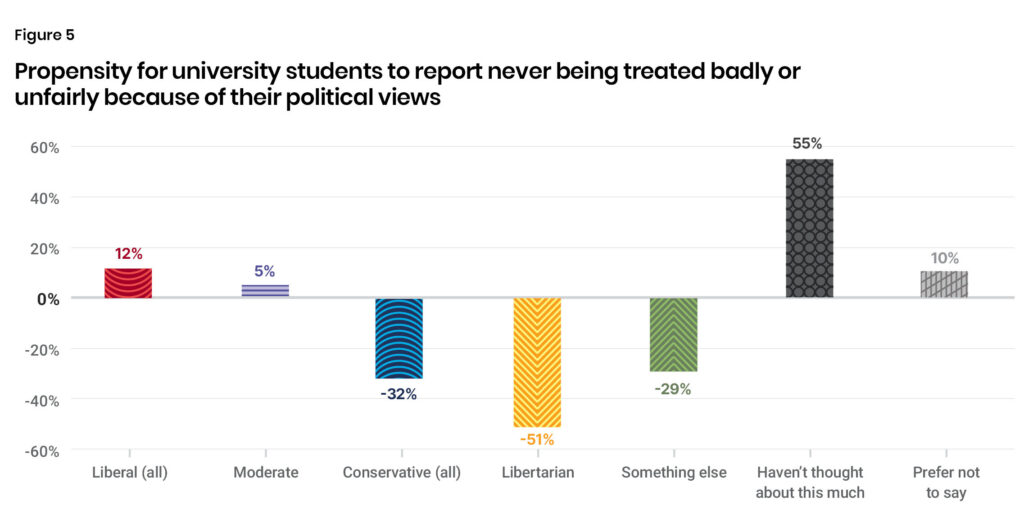

The frequency of reported mistreatment is worth unpacking further. Those who “haven’t thought about [politics] much” are 55 percent more likely than the average student to report never being treated poorly or unfairly for their political views (Figure 5). Liberal-leaning students are 12 percent more likely than average to report no mistreatment. Conservative-leaning students are one-third less likely and libertarian students are 51 percent less likely than the average student to report never being mistreated for their political views. Fully 85 percent and 74 percent of students who self-identify as “very conservative” or “libertarian,” respectively, report being treated badly or unfairly, because of their political views, at least once a year. Excluding “slightly conservative,” nearly one-third (31.7%) of “conservative” and almost half (48%) of “very conservative” students perceive being mistreated for their political views as frequently as every few weeks. Mistreatment for their political views is perceived as a weekly occurrence for nearly one out of every three (29.6%) “very conservative” students.

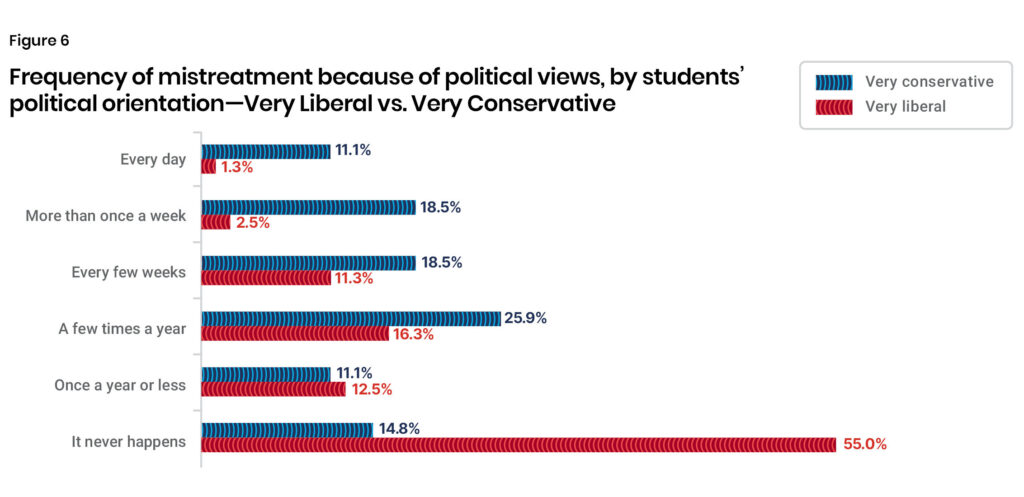

Isolating only the politically “very liberal” and “very conservative” reveals a highly skewed imbalance of how university students perceive being treated on campus (Figure 6). Very liberal students are nearly four times more likely to report never being mistreated for their political views. Daily, very conservative students are 11 times more likely to report experiencing mistreatment, and, on a weekly basis, very conservative students are 7.4 times more likely to report being treated badly or unfairly for their political views more than once a week.

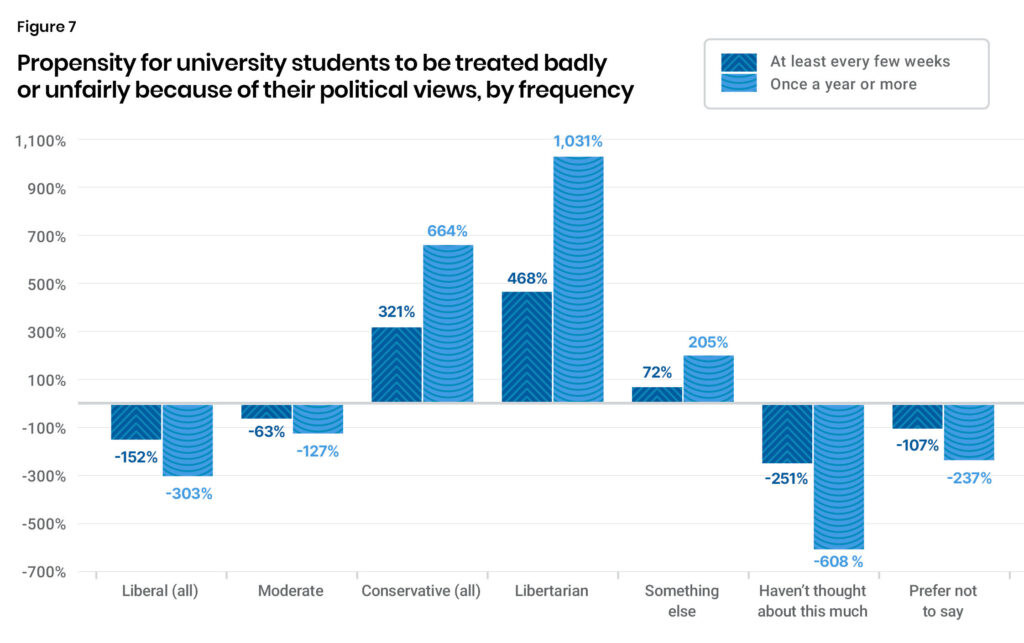

As frequently as every few weeks libertarian and conservative-leaning students are, respectively, 5.7 times and over four times more likely to perceive being treated badly or unfairly because of their political views. Compared to the average student, libertarian students are 11 times, and conservatives 7.6 times, more likely to be treated badly or unfairly because of their political views, once or more per year (Figure 7).

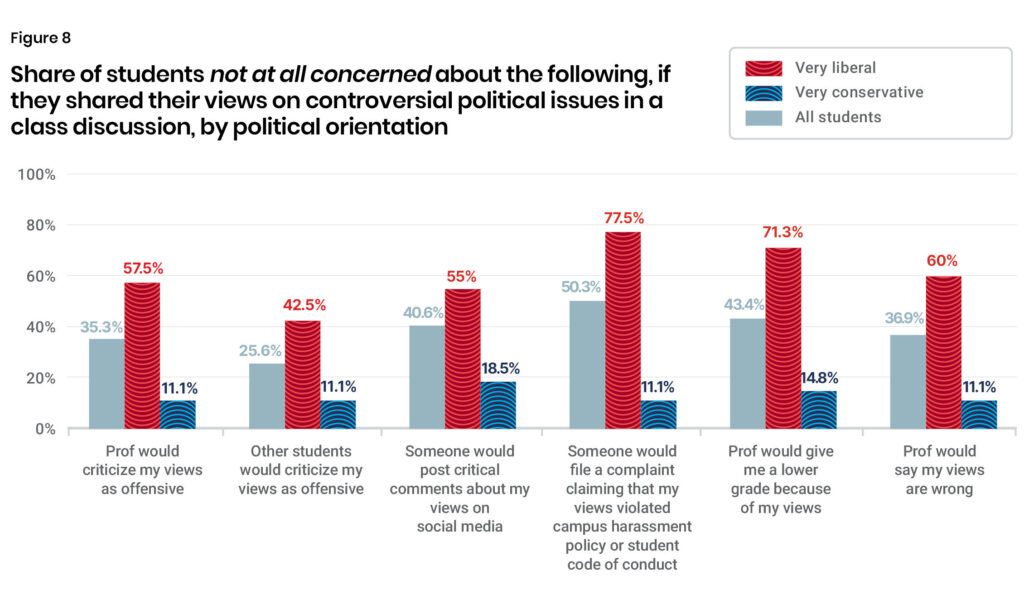

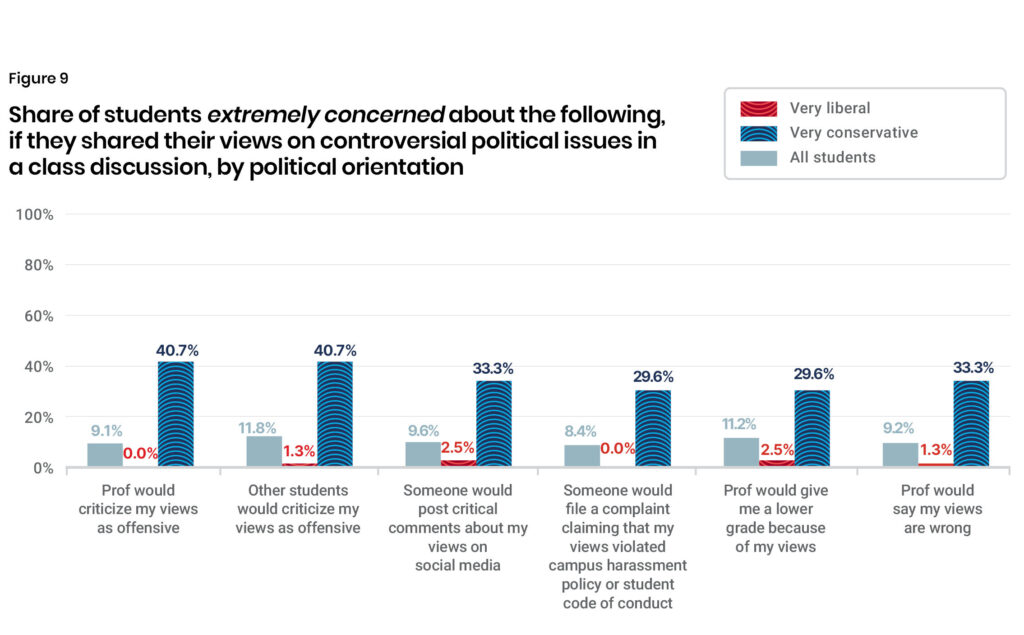

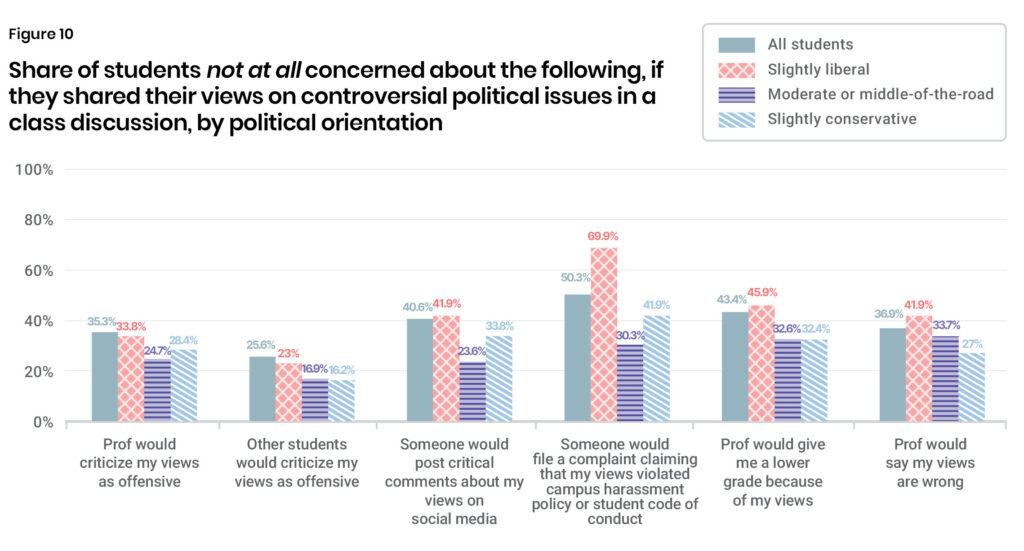

This perceived mistreatment comes from multiple sources. Nearly 90 percent of “very conservative” students are concerned that both professors and students would criticize their political views as offensive (Figure 8), with over 40 percent reporting feeling “extremely” concerned (Figure 9). By contrast, zero percent of “very liberal” students report extreme concern about professors criticizing their politics, and merely 1.3 percent are extremely concerned about other students’ criticisms. If they shared their political views, 29.6 percent of very conservative students report extreme concern that a professor would lower their grade, and someone would file a complaint claiming their views violate campus harassment policy or student codes of conduct. No students identifying as very liberal reported extreme fear of receiving the same complaints, and just 2.5 percent of such students expressed being extremely concerned a professor would lower their grades over political views. More than three in four students identifying as being very liberal expressed being not at all concerned that sharing their political views would result in a formal complaint, compared to 11 percent of students who identify as very conservative. Fully 85 percent of students who identify as very conservative fear a lower grade for expressing their political views.

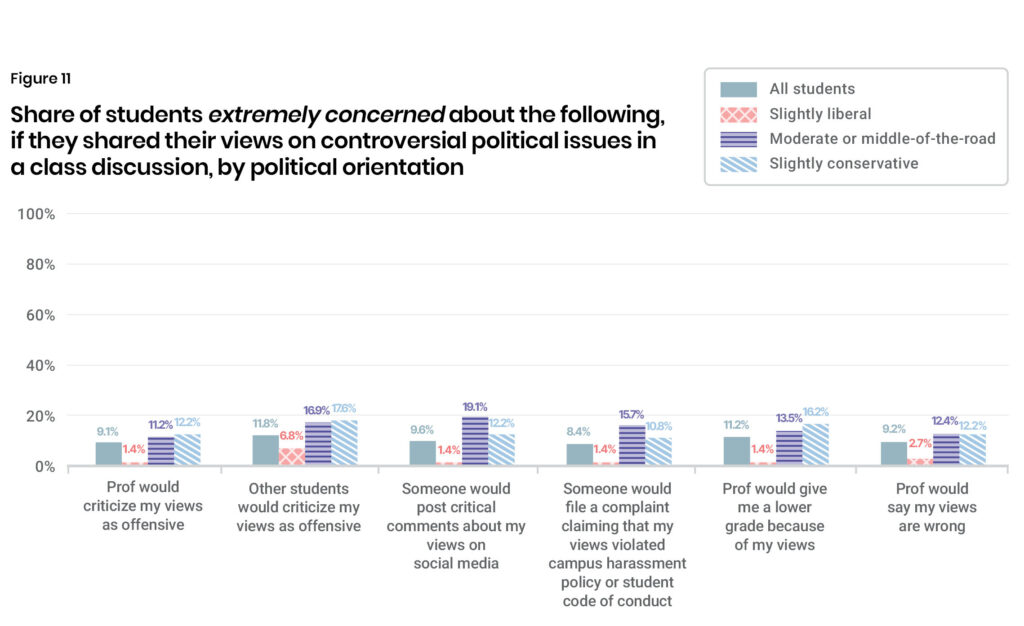

Additionally, conservatives and libertarians are not alone in this regard, as moderates similarly do not feel free to share their political views. Just 17 percent of political moderates are not at all concerned that students would find their political views offensive. More than two-thirds of them are at least somewhat concerned that both someone would file a formal complaint and that professors would lower their grades if their moderate views were expressed (Figure 10). Nearly one-in-five moderates is extremely concerned that other students would post critical social media content about their political views, if expressed in class; less than 2 percent of slightly liberal students share those concerns (Figure 11). Both moderate and slightly conservative students are more likely than the average student to be extremely concerned—in every category—to experience consequences for sharing their political views. Conversely, slightly liberal students are many times less likely to be extremely concerned about any pushback for sharing their views.

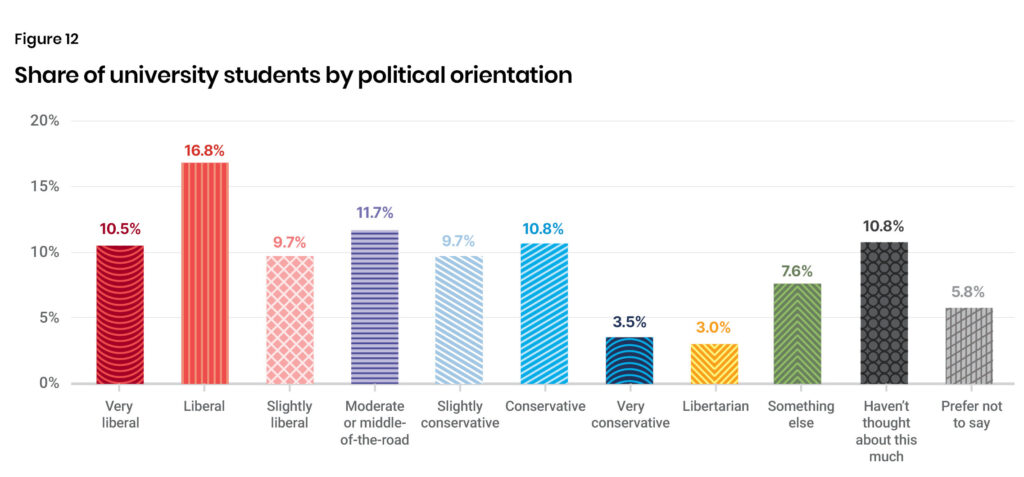

And these disparities are understated, since the largest percentage of students lean liberal (37%, when also including “very” and “slightly”). Figure 12 shows the political orientation of university students in our sample, and it is generally what one would expect. University students are over 50 percent more likely to be liberal than conservative and three times more likely to be liberal than moderate. In other words, the “average” university student is much more likely to hold liberal viewpoints, and thus the reticence of students espousing non-liberal views to express their viewpoints is even more pronounced.

It appears reasonable to conclude that politically liberal views are welcomed and supported at Canadian universities, given such a large gap between liberals’ comfort and not only conservatives but also libertarian and even moderates’ reluctance in sharing their honest political opinions. Students who identify politically as “something else,” like liberals, are also less likely to be concerned about any consequences for sharing their political perspective (see figures C2 and C3 in Appendix C). Their political positions are unknown, but presumably “something else” includes Marxist, social democrat, and/or green ideologies.

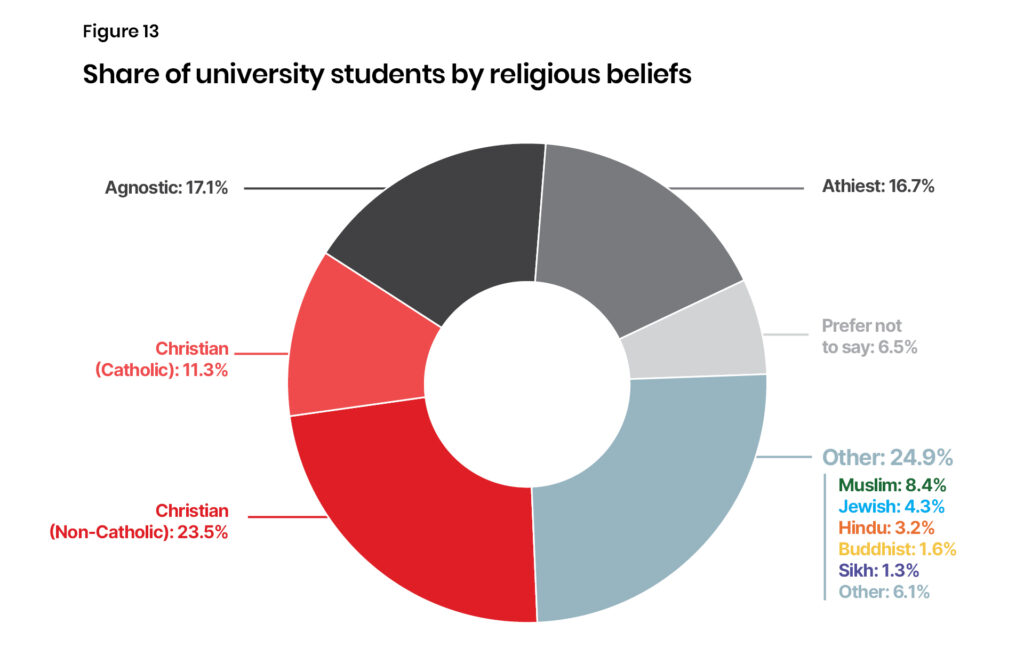

Two out of every three university students are religious—consistent with the general Canadian populationii—after excluding the 6.5 percent who wish to not disclose their faith position. Of the 93.5 percent of students who disclose their religious beliefs, 37 percent are Christian, 36 percent either agnostic or atheist, and the remaining 26.6 percent practice or identify with another faith tradition. The share of secular and non-religious students is nearly identical to the general population of Canada. The Christian population, however, is significantly underrepresented on campus (34.8% of university students versus 53.3% of Canada’s population), while the Muslim (8.4% vs. 4.9%) and especially Jewish (4.3% vs. 0.9%) populations are overrepresented. Figure 13 presents the full religious spectrum on campus.

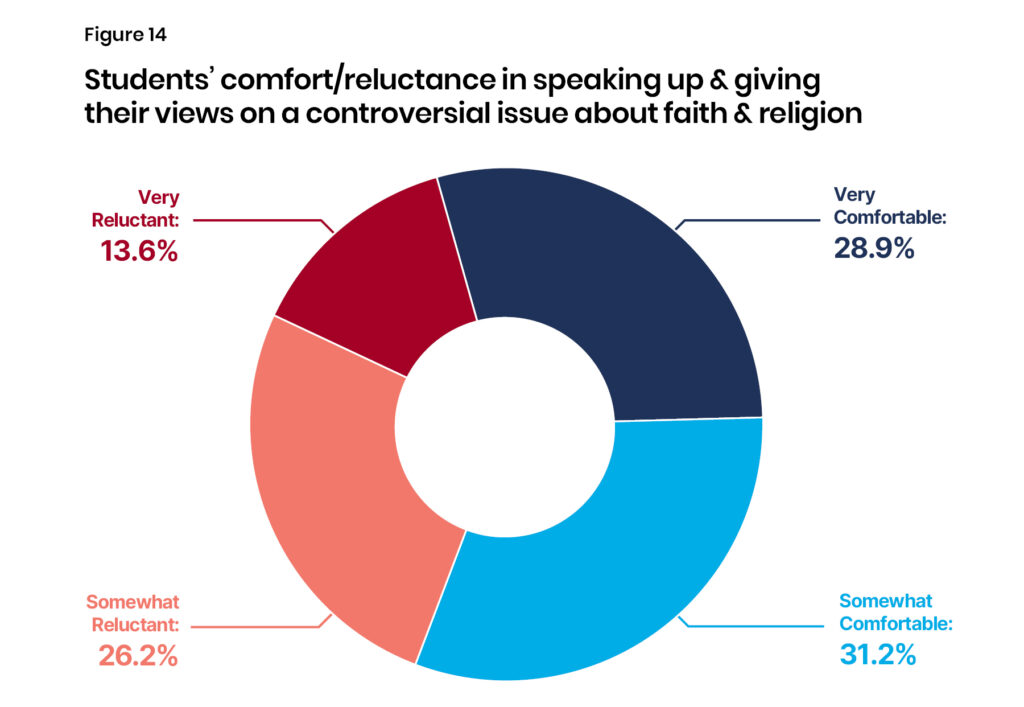

Of the five controversial topics, religion (and race) is—by a slight margin—the topic on which students are most likely to be comfortable sharing their views. Yet, when compared to speaking up on non-controversial issues, university students are less than half as likely to be “very comfortable” and seven times more likely to be “very reluctant” in sharing their views on a controversial issue about faith and religion. Exactly 40 percent are reluctant to give their honest opinion on faith and religion (Figure 14).

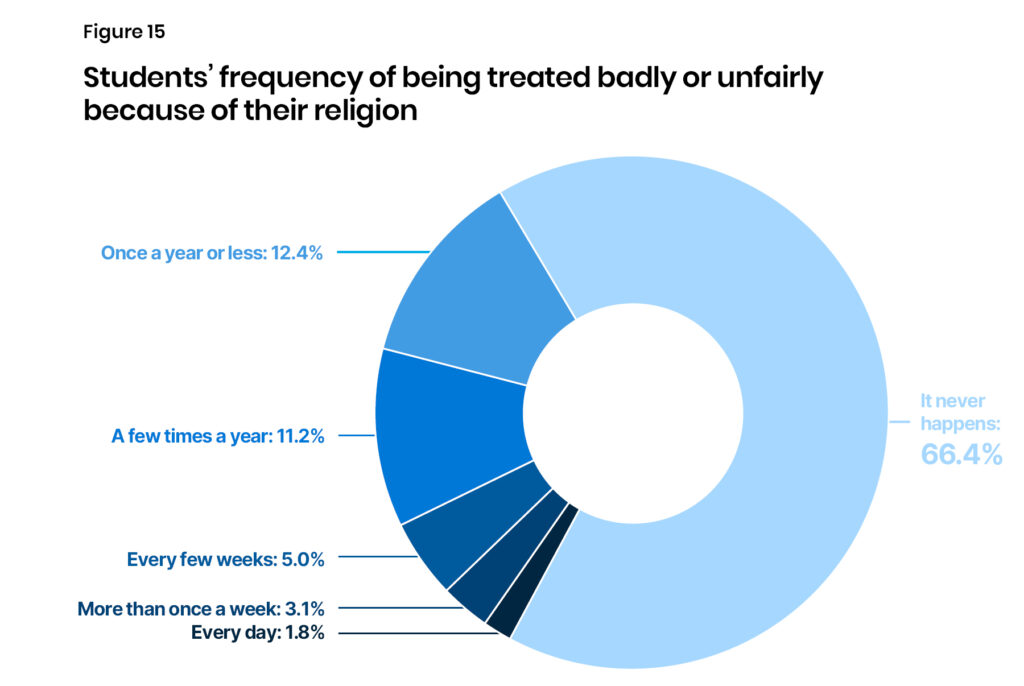

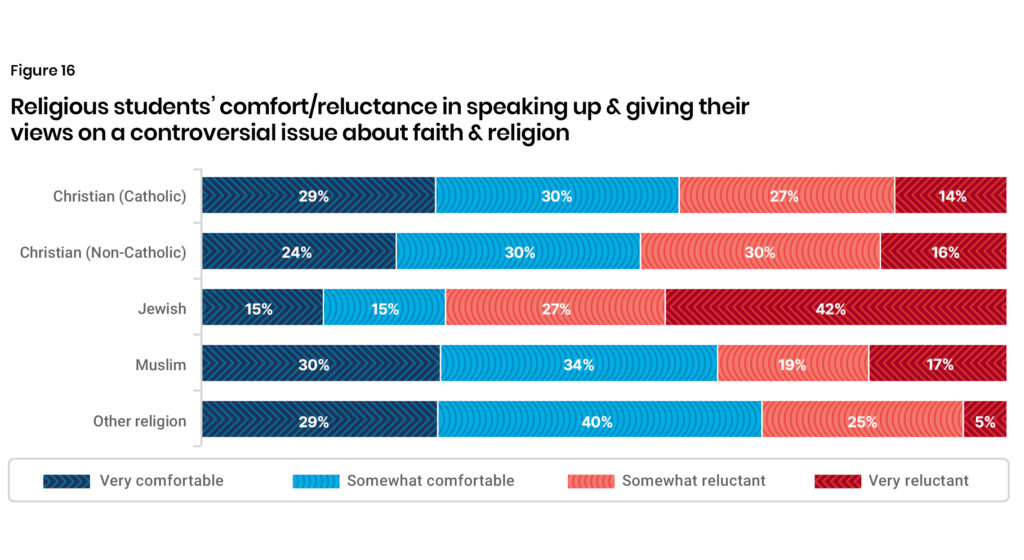

Two-thirds of students report never being mistreated because of their religion (Figure 15). Figure 16 shows that most religious students are comfortable speaking up and giving their views on faith and religion.

There is one exception, however. On controversial issues about faith and religion, Jewish students are four times more likely to be “very reluctant” to speak up and share their views in class discussions. Jewish students are half as likely to feel “very comfortable” and “somewhat comfortable” giving their perspective.

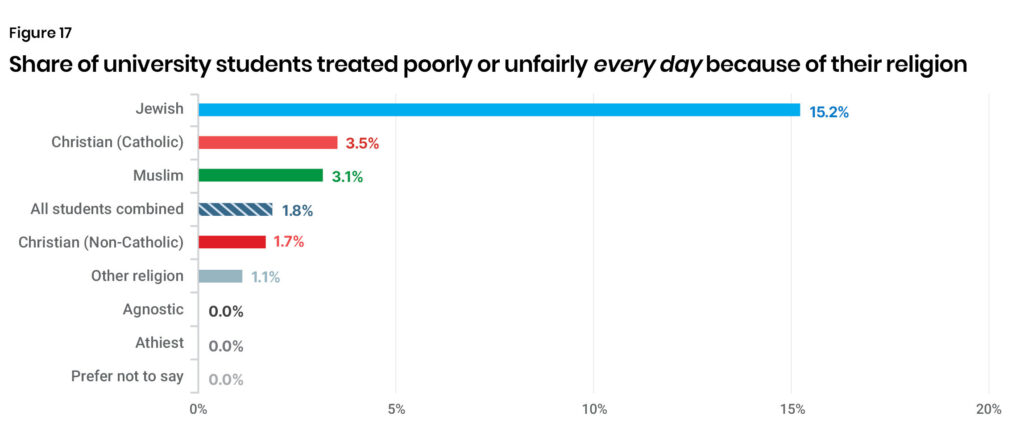

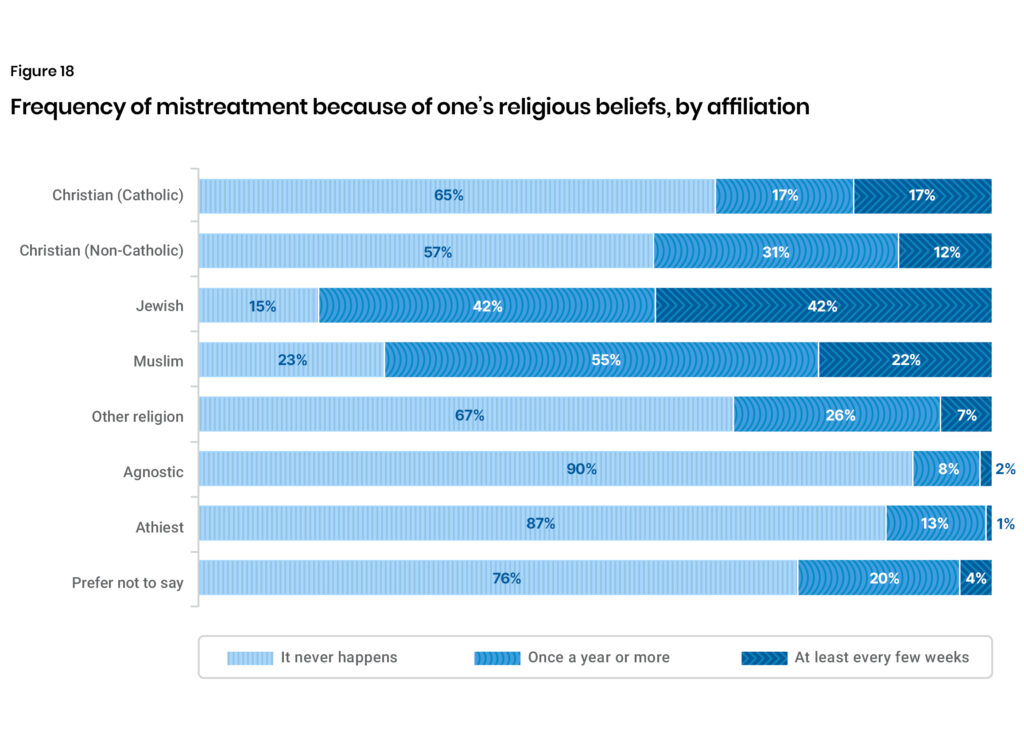

The unwillingness of Jewish students to speak up in class is almost certainly due to the fact that 15 percent of them experience daily abuse on campus for being Jewish (Figure 17). At least once a year, 84 percent of Jewish students experience antisemitism at university; only 15 percent never experience it (Figure 18).

By contrast, 90 percent of agnostics, 86.6 percent of atheists, and 75.5 percent of “Prefer not to say” report never being treated badly or unfairly, as university students, because of their religion. Not a single participant who identified as agnostic, atheist, or “Prefer not to say” reported daily mistreatment.

Furthermore, Jewish students are 42 times more likely than atheists and 21 times more likely than agnostics to be mistreated for their religious views at least every few weeks.

The experience of Catholic and Muslim students is also concerning based upon the data. While their comfort or reluctance in speaking up and sharing their views on controversial religious issues in class diverts little from the average, Catholics are the second most likely to experience daily mistreatment—twice as likely as both the average student and fellow Christian students. Muslim students are three times less likely to report that they never experience religious mistreatment. Muslim university students are twice as likely to be treated badly or unfairly because of their religion both “at least every few weeks” and “once a year or more.”

However, compared to students in general, the average Muslim student is more comfortable speaking out and giving an honest view on all topics—controversial or not—save two: gender and sexuality. By contrast, of the five controversial topics, there is none in which Jewish students feel more comfortable than their peers in sharing their views.

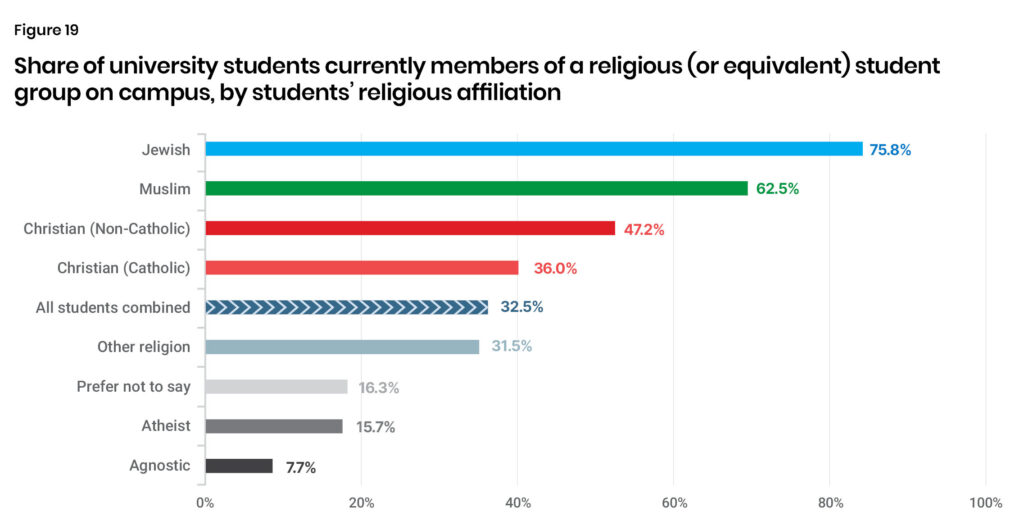

In light of these concerns, it is interesting but not surprising to see Jewish and Muslim students with a higher tendency for solidarity and greater engagement in their own religious community on campus (Figure 19).

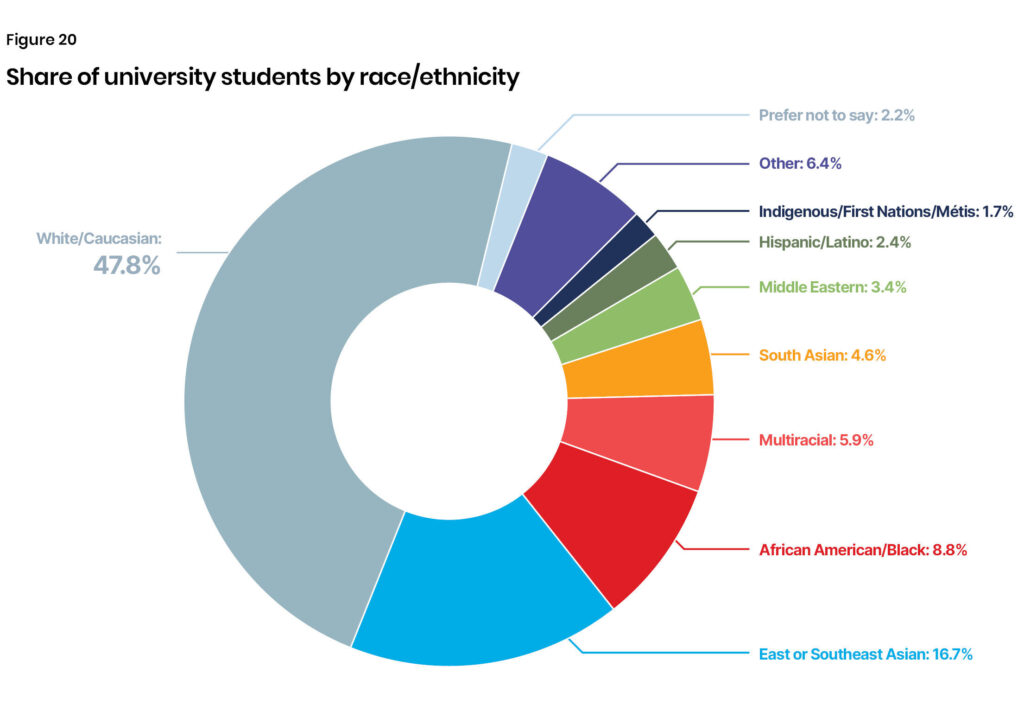

Visible minorities are overrepresented in our sample, making up a combined 52 percent of respondents—18 percentage points higher than their share of enrolled postsecondary students in Canada. This allows for more meaningful comparisons, especially at a more granular level. Still, despite falling below the majority, at 48 percent, the white cohort remains the largest by a considerable margin—nearly three times that of the next largest cohort. East/southeast Asians (including Chinese, Filipino, etc.) is the second largest cohort, at 16.7 percent, followed by black or African-American, at 8.8 percent (Figure 20). Both are within two percentage points and are consistent with the cohort size rankings of Statistics Canada’s population data of all undergraduate students in Canada.iii

Students are more comfortable talking about race (and religion) than politics, gender, and sexuality. When it comes to controversial racial issues, university students are two-thirds less likely to be “very comfortable” and seven times more likely to be “very reluctant” in sharing their views, compared to non-controversial issues. The reluctance to speak honestly about race is identical to the reluctance to speak honestly about religion—14 percent “very reluctant” and 26 percent “somewhat reluctant,” for a combined share of 40 percent of students hesitant to share their views on race (Figure 21).

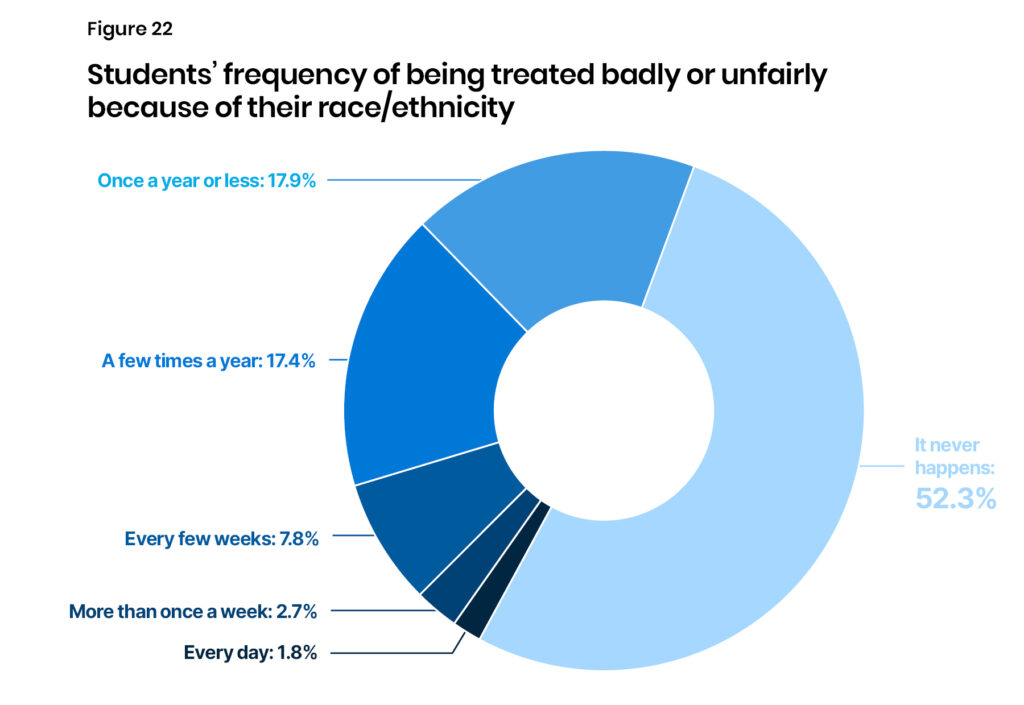

The frequency of reported mistreatment for one’s race is similar—albeit, slightly less frequent—to that of political discrimination. Nearly 48 percent of students experience racial discrimination at least occasionally. However, the data does not support broader concerns with racism on campus. Daily, less than 2 percent of students experience ill treatment on a daily basis because of their race (Figure 22).

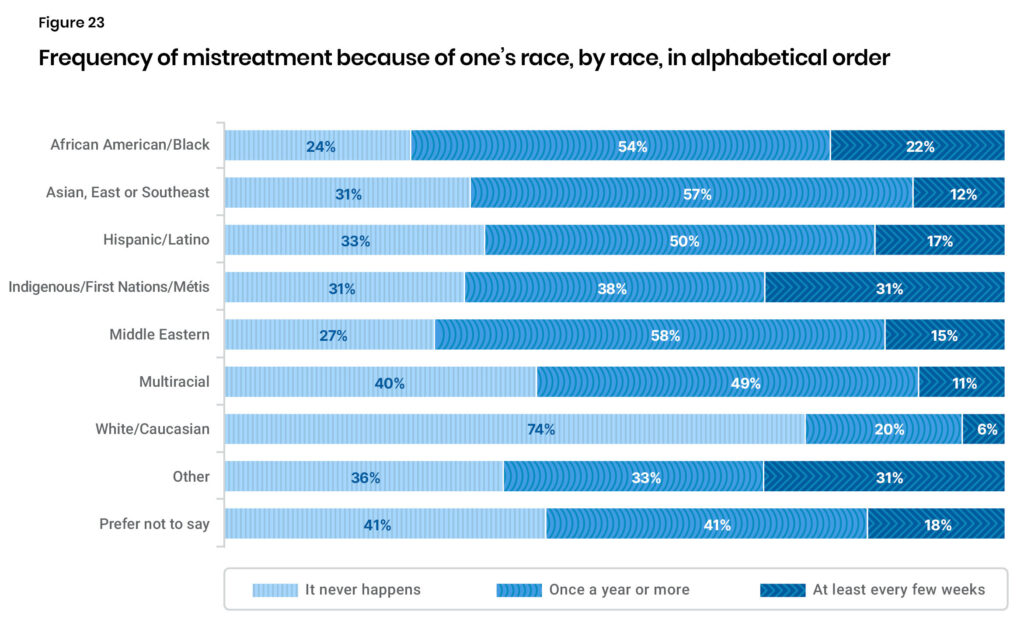

The methodology for this study was limited to subjective reports of ill-treatment, but, where reported racism does occur, it is experienced primarily by visible minorities. There is a near-perfect “fifty-fifty” split between, first, the share of white and non-white students, and second, those who reported some form of racism. When cross-tabulating the results, white students are by far the least likely to report any mistreatment due to race, with three in four white students never experiencing racism. Indigenous and South Asian students are the most likely to report being mistreated at least every few weeks, while black and Middle Eastern students are the least likely to report never being mistreated for their race (Figure 23).

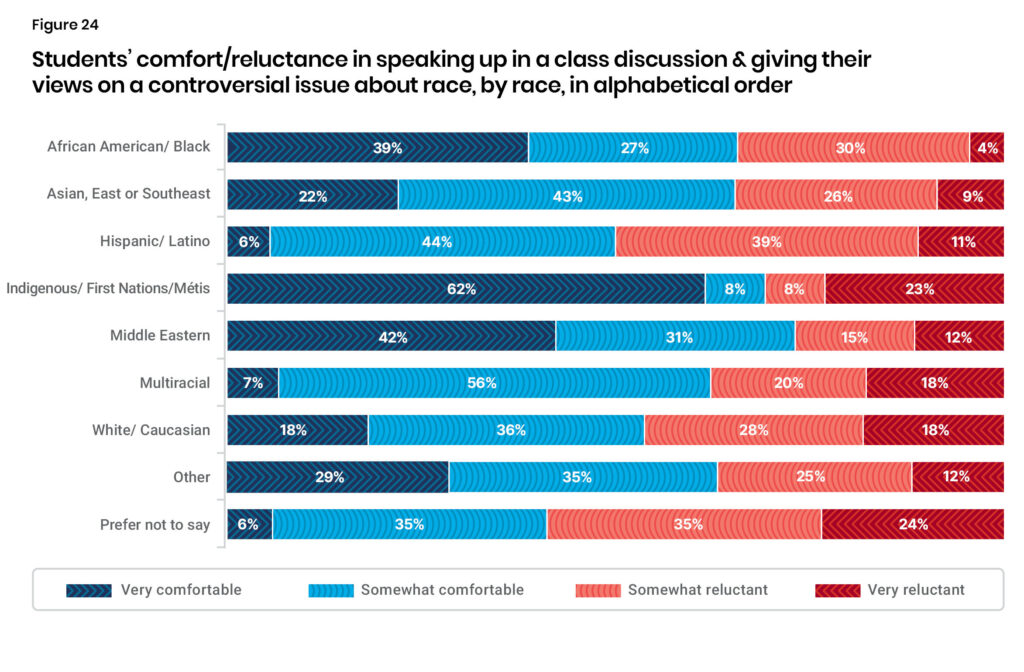

In contrast, the data indicates that reported discrimination is unlikely to happen in the classroom. Indigenous students are by far the most likely—61.5 percent—to report feeling “very comfortable” speaking up in a class discussion and giving their views on a controversial issue about race (Figure 24). African American or black students are one of the most comfortable and the least likely to be “very reluctant” to share their views on race, at 4.5 percent—half that of the second-least hesitant, East or Southeast Asians (8.7%). Combining “very comfortable” and “somewhat comfortable” responses, non-white students feel greater liberty on this issue, with Middle Eastern students, in particular, the most likely to feel comfortable discussing race and ethnicity in class (73%).

Openness to expressing one’s views on race reveal paradoxical findings. By far the least likely to be “very comfortable” sharing their views are Hispanic/Latino and multiracial students, and by far the most likely to feel “very comfortable” are indigenous and Middle Eastern students. And black students are the least likely to feel “very reluctant” to give their perspective on race. Overall, the data is not one-directional in that there is a scatter of outcomes, the meaning of which goes beyond the scope of this study. Specifically, this study did not explore the source of the perceived racism and whether these situations involved formal complaints. It is possible—even plausible—that, where racism occurs, it is experienced by and towards sub-cohorts within cohorts (e.g. Ulster versus Irish; Punjabi versus Pakistani, Palestinian versus Israeli, etc.).

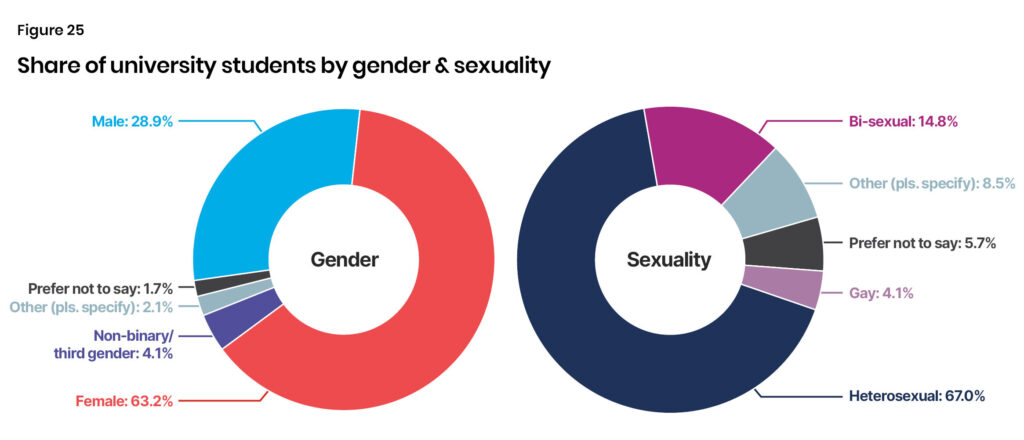

Gender and sexuality are the final two potentially controversial topics on which we gauge free speech on campus, and their similarities and differences are best highlighted by presenting them together. About 3 percent of Canada’s population aged 15 and older identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual; this figure doubles to 6.4 percent among the 15 to 24-year-old cohort. Even fewer identify as transgender or non-binary persons—less than 1 percent of Canadian postsecondary studentsiv—so oversampling was needed for analysis. Figure 25 shows that two-thirds of respondents identify as heterosexual and one-third as gay, bisexual, or other. Over 6 percent identify as non-binary or third gender or other, 63 percent female, and 29 percent male—the latter are slightly underrepresented from the Statistics Canada average.

Gender and sexuality are the most polarizing topics. They have the largest share of students reporting they are “very comfortable” (32%) freely expressing their views on controversial issues on these matters, as well as the largest share feeling “very reluctant” (22%) (Figure 26). Compared to non-controversial issues, university students are less than half as likely to be “very comfortable” and 11 times more likely to be “very reluctant” in sharing their views.

Gender is the only one of the five topics to which a majority (61.3%) of university students attribute mistreatment at least once a year. Conversely, the overwhelming majority (73.5%) are never mistreated because of their sexual orientation (Figure 27).

At least periodically, gender nonconforming and gay students reported mistreatment in some form. Moreover, 9 in 10 students who identify as non-binary or third gender experience poor or unfair treatment because of their gender at least once a year; half experience mistreatment at least every few weeks (Figure 28). It is similar for “other” gender, too. Likewise, 9 in 10 gay students also experience mistreatment at least once a year; for 1 in 4, it is every few weeks (Figure 29). However, as with race, less than 2 percent of students experience daily mistreatment for either their gender or sexual orientation Additionally, 3 percent of non-binary or third gender, 12.5 percent of “other” gender, 6.5 percent of gay, and 0 percent of bi-sexual students are treated badly or unfairly for their gender or sexual orientation every day. For the overwhelming majority, mistreatment is infrequent.

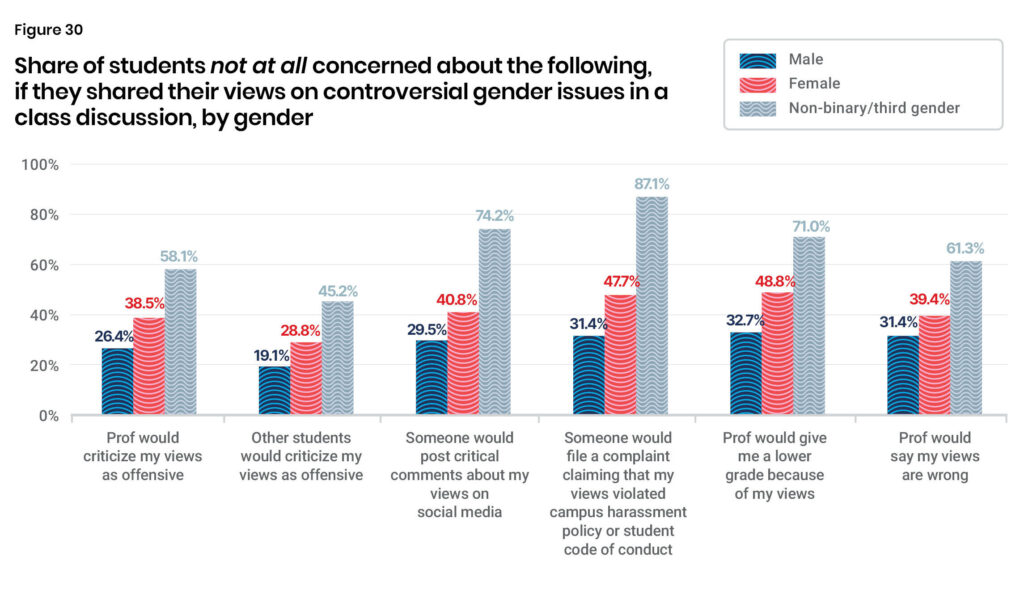

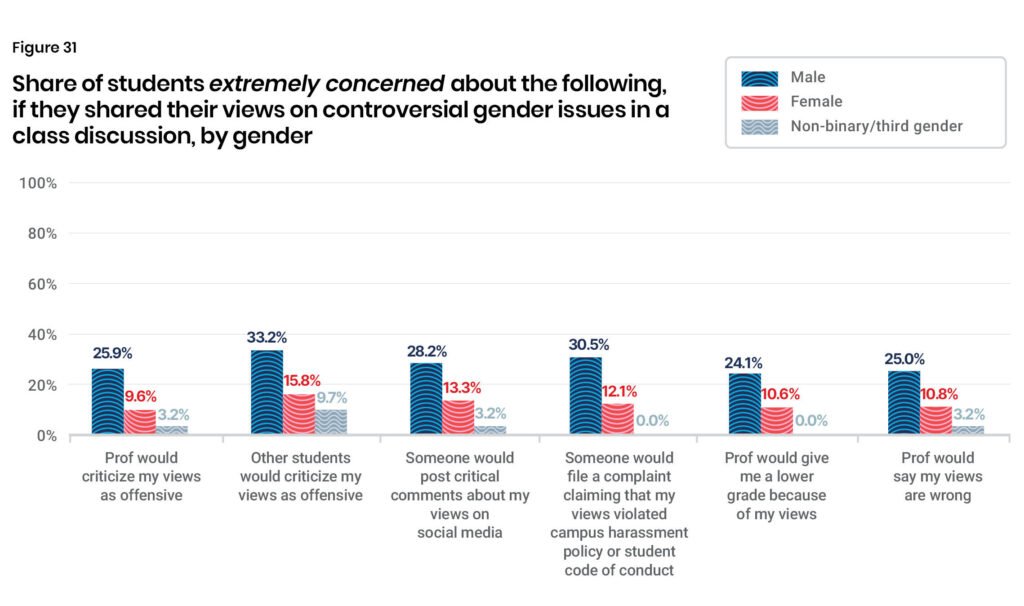

Moreover, the source and severity are unclear. Only 55 percent of non-binary or third gender students are at all concerned that other students would criticize their views as offensive, about 40 percent have any concerns about disagreement from professors, and only 1 in 4 are at all concerned about critical comments on social media. Conversely, two-thirds of male students are concerned about the consequences of sharing their views (Figure 30). Nearly one in three male students are extremely concerned about a formal complaint and one in four of a lower grade, if they gave their honest opinion; neither is the case for even one non-binary respondent (Figure 31).

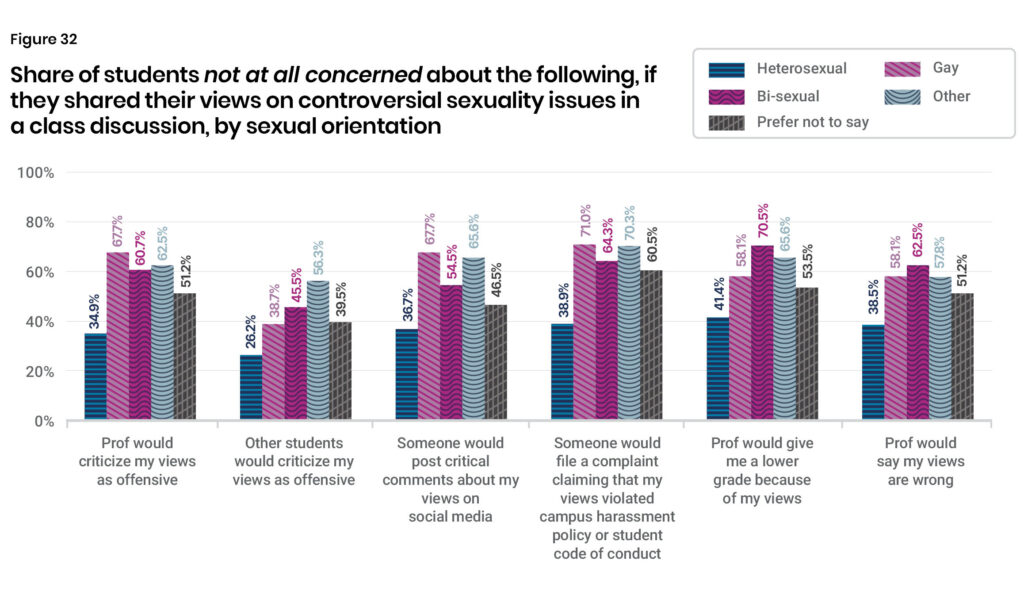

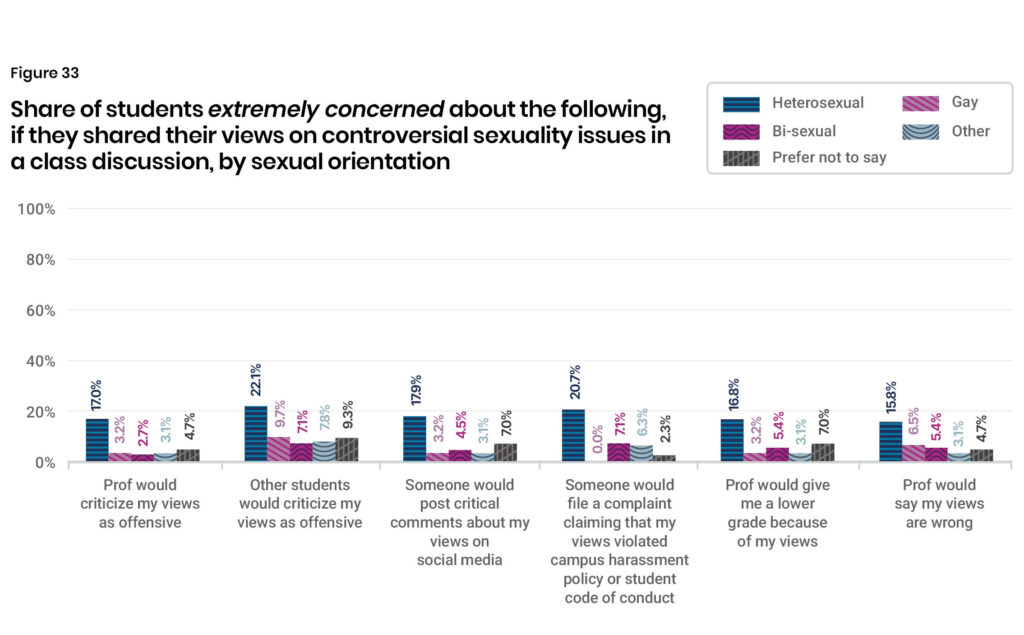

Likewise, around two-thirds of heterosexual students report concerns about being honest about their views on sexuality, while the overwhelming majority of gay, bi-sexual, and other students do not (Figure 32). Additionally, one in five heterosexual students are extremely concerned about a formal complaint and one in six of a lower grade or critical comments on social media, if they shared what they believed about sexuality in class. This is not the experience of gay, bi-sexual, and other students; less than 10 percent share any of these extreme concerns (Figure 33).

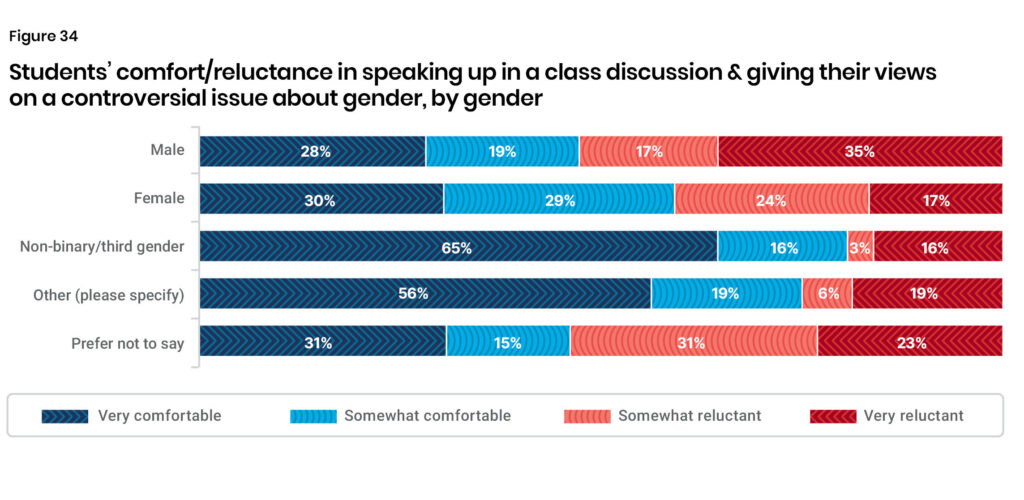

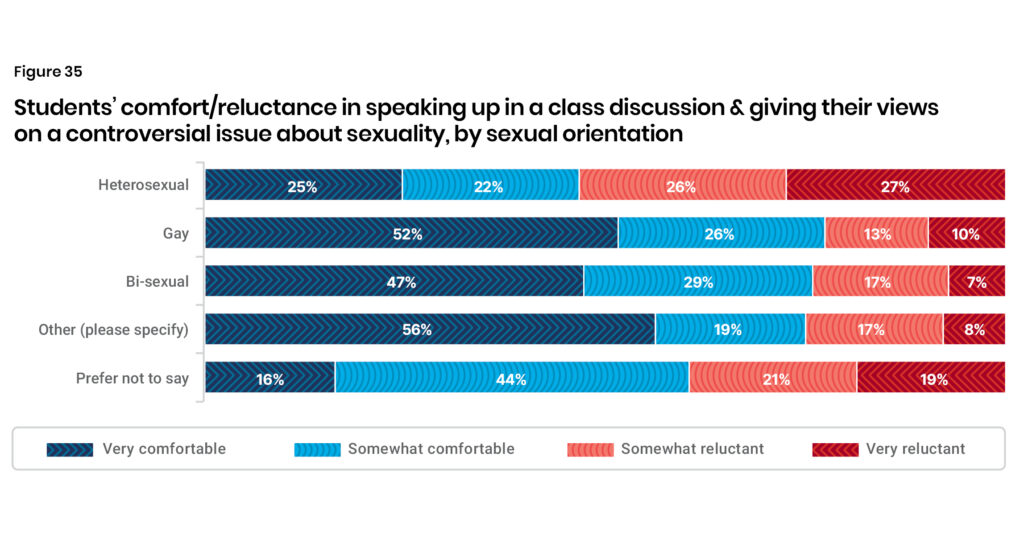

Gender nonconforming and gay students are much more likely to be comfortable sharing their views in class. Two-thirds of non-binary students are very comfortable and over 80 percent are comfortable sharing their views in class on a controversial issue about gender (Figure 34). Similarly, about half of gay and bi-sexual students are very comfortable and three-quarters are comfortable speaking up and giving their opinion in a discussion on a controversial issue on sexuality (Figure 35).

In summary, like race, the gender and sexuality findings are mixed. Those who rarely experience any mistreatment for their gender or sexual orientation—heterosexual males—are, by far, the least likely to feel at liberty to share their views on those issues. Whereas, despite experiencing reported periodic mistreatment, all others feel free to openly discuss controversial gender and sexuality issues without fear of reprisal.

Thus far, the findings have been isolated to one of the five controversial issues. New insights emerge when the findings are cross-tabulated by issue.

After dozens of contingency table analyses, we observed that almost all of the data can be better understood by categorizing the respondents and their responses into six distinct personas—each considerably distinct from “average.”

With a small amount of overlap, over 80 percent of the sample can be roughly divided into four parts: east/southeast Asians, non-white Abrahamic religious, white secularists, and straight white religious students. Three have a unique persona that accurately represents the majority of students that fall within the respective categorization. For non-white Abrahamic, it requires further segmentation, from which three distinct personas emerge, giving a total of six personas for analysis.

For convenience, each persona has been given a nickname: in order of analysis, Zhang, Ebony, Aabidah, Ari, Libby, and Peyton. Distinctions in politics, religion, race, gender, sexuality—and cross-tabulations between—as well as the comfort level of each persona, unveil richer insights into freedom of expression on campus.

Zhang

“Zhang” represents any randomly selected one of the 127 east or southeast Asian students in the sample. Politically moderate, compared to the average student, Zhang is much more likely to identify as “middle-of-the-road” or “slightly” either liberal or conservative; still, there is a 37 percent chance Zhang leans liberal, with only a 22 percent chance of leaning conservative. Twenty-five percent less likely to be atheist, Zhang is more than three times more likely to be Hindu and four times more likely to be Buddhist. Neither more nor less likely—from the average—to be male or female, Zhang is much less likely to be anything other than male or female and only slightly more likely to be heterosexual. When it comes to potentially controversial class discussions, Zhang is more comfortable than the average student openly discussing controversial views on politics, religion, and race, but Zhang is less likely than the average student to feel comfortable sharing an honest opinion on gender and sexuality.

Ebony

Female black respondents outnumber male black respondents three to one, so, for analysis, the “Ebony” persona is assumed to be female. She represents any randomly selected one of the 67 black or African-American students in the sample. Politically, Ebony is less likely than other students to be liberal, even less likely to be conservative, and even less likely to be “something else,” as Ebony is more than twice as likely to both have not given much thought to politics and “prefer[s] not to say.” (Excluding the 9.6 percent undecided and 22.6 percent who prefer not to say, nearly half of black students lean liberal, and the remaining half is evenly divided between moderate and conservative.) Ebony is twice as likely to be religious, and—if we exclude “prefer not to say”—there is an 80 percent chance she is a Christian. The data suggests that there is zero chance that she is neither male nor female, and Ebony is much more likely to be heterosexual. On politics, religion, and race, Ebony is more comfortable sharing her views than the average student, but she is less comfortable discussing what she believes regarding gender and sexuality.

Aabidah

The 64 Muslim students in the sample are represented by “Aabidah.” Politically, excluding those who have not thought much about politics or prefer not to say, there is a 40 percent chance she leans liberal versus 30 percent conservative and nearly 20 percent moderate. In other words, compared to other students, she is less likely to be liberal and neither less nor more likely to be conservative. There is zero chance that she is libertarian, and Aabidah is 23 percent more likely to be “something else” politically—perhaps green, Marxist, or Shariah. Aabidah is 93.5 percent less likely to be white, 49.6 percent more likely to be east/southeast Asian, 5.5 times (448%) more likely to be Middle Eastern, and 3.7 times (267.6%) more likely to self-select an “other” race. There is a 1.6 percent chance she identifies with a gender other than male or female, and Aabidah is much more likely to be heterosexual. She has above average comfort sharing her views on everything but gender and sexuality.

Ari

While half the size (n = 33) of the next-smallest persona, given inordinate mistreatment on postsecondary campuses, it is critical to include a persona, “Ari,” that reveals the typical Jewish student experience. (Of note, all data was collected by April 30, 2023, and thus precedes October 7, 2023 and the considerably more intense hostilities that followed.) Ari’s comfort level speaking out and giving an honest opinion is below average on every controversial topic. Politics is especially front of mind: Ari is almost half as likely to “have [not] thought about” politics and to “prefer not to say.” This is particularly interesting as, on most other topics, Ari is much more likely to “prefer not to say.” There is about a 50 percent chance Ari leans liberal, which is considerably above average. Ari is as likely as the average student to be white, about 50 percent more likely to identify as multiracial, 77 percent more likely to be Middle Eastern, and three times more likely to identify as an “other” race. On gender and sexuality, Ari is much more likely to be nonconforming and is 23 percent less likely to be heterosexual. On politics and religion, Ari is half as likely to be comfortable sharing her views, compared to the average student.

Libby

“Libby” represents the 23.6 percent (n = 179) of university students who identify as either agnostic or an atheist, and either white or Hispanic/Latino.1 Excluding “haven’t thought about [politics]” and “prefer not to say,” the chances that Libby is a liberal or conservative are 58 percent and 11.5 percent, respectively. In other words, compared to the average student, Libby is 45 percent more likely to be liberal and 56 percent less likely to be conservative. There is a 6 percent chance Libby is libertarian: double the average. Libby is much more likely to be gender nonconforming and anything other than heterosexual. Given the earlier findings, it is unsurprising that Libby is more comfortable discussing all five controversial issues in class—most especially, sexuality (35.4% more than the average student).

After controlling for politics, if we only include politically liberal students, the size of this persona drops by about one hundred students—to 75 or 78 respondents, depending on the crosstab. Any randomly selected student in this subcategory—i.e. a white or Latino, secular, liberal—is 42.4 percent less likely to be male, 2.5 times (151.4%) more likely to be non-binary/third-gender, and 82.7 percent more likely to be an “other” gender; this student is also 63 percent more likely to be gay, 89 percent more likely to be bi-sexual, and almost three times (168%) more likely to be an “other” sexual orientation. Most notably, this student is the most comfortable discussing every controversial topic—usually, by a considerable margin—most especially sexuality (57.6% above average) and gender (49.2% above average). (On controversial religious matters, there is a three-way tie between Ebony, Aabidah, and this subsample of Libby; they are all slightly over 7 percent more likely to be comfortable expressing their views. Albeit, this subsample of Libby is the most likely of all groups to be “very comfortable” giving honest, controversial views on religion [43.6%].)

Peyton

“Peyton” represents the 22 percent of university students (n = 169) who are white, religious, and heterosexual. Peyton is 22.6 percent more likely to be male, more than twice as likely to be politically conservative, 44 percent less likely to be politically liberal, and 3.5 times (246%) more likely to prefer not to reveal their gender. There is a 0.6 percent chance Peyton is a gender nonconformist. On every measure of openness to discussing controversial issues in class, Peyton is below average.

Persona summary

In summary, only one of the six personas—less than one-quarter of students—feels free to honestly discuss what they believe about any controversial issue; the majority of students heavily self-censor on at least two issues. Zhang, Ebony, and Aabidah are quite comfortable openly discussing their views on any controversial subject in a university classroom, except gender and sexuality. On these two issues, they are uncomfortable (presumably because their views are likely outside the prevailing zeitgeist). Ari and Peyton are uncomfortable discussing anything controversial. This does not mean they remain silent. There is some evidence in the data and plenty from other sources indicating that they do speak up—which, given the environment, requires courage. Universities are neither a safe space nor a forum open to debate and free inquiry for Ari and Peyton. Only Libby is comfortable speaking her mind on any controversial topic.

In light of the persona analysis, two items warrant a deeper dive: race and religion. As established earlier, two-thirds of university students are religious, and over half are of non-European ethnicity. Of university students that are both religious and non-white, a mere 23 percent report never experiencing mistreatment for either their faith or race.

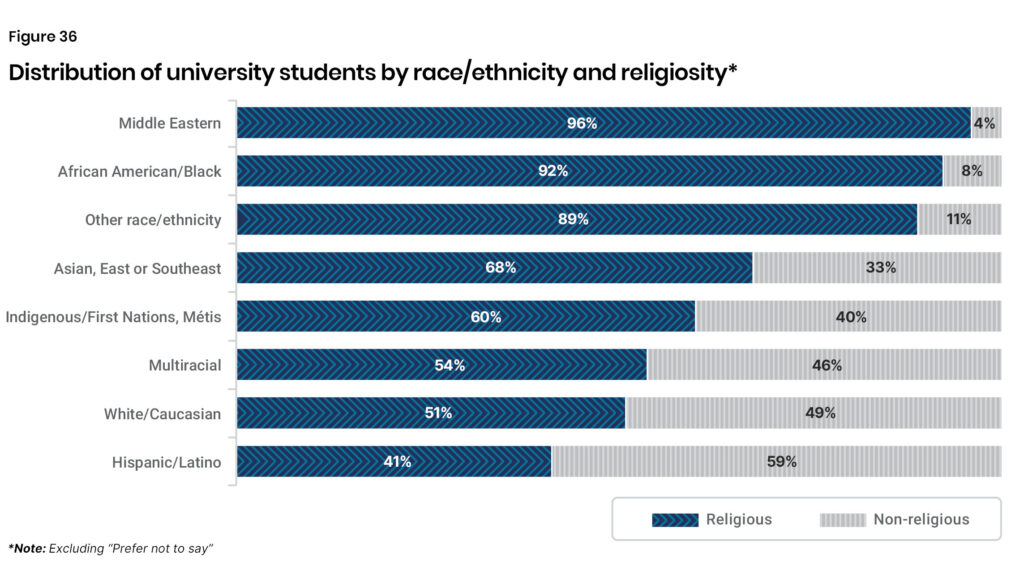

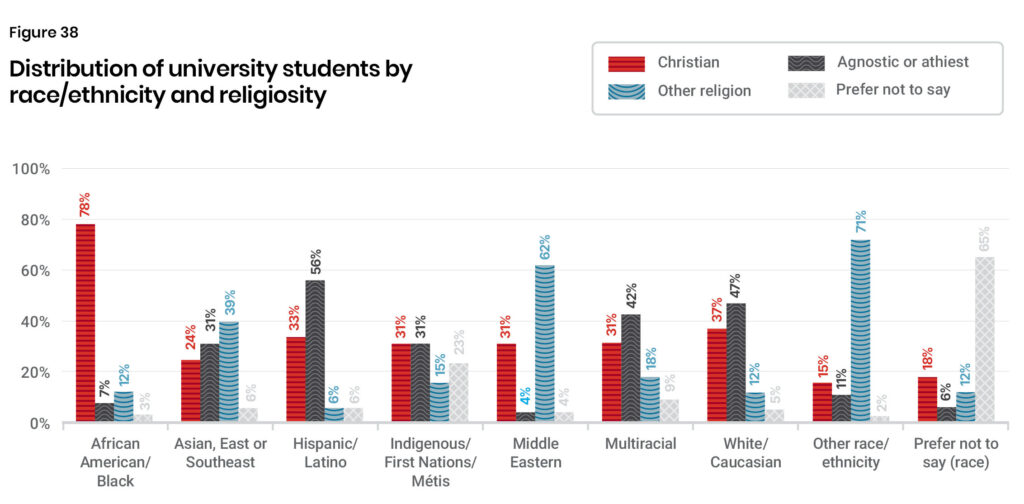

Figure 36 overlaps race and faith, showing the share of religious students within each ethnic cohort. With the exception of Hispanic/Latino, all ethnic cohorts are predominantly religious—even white students, albeit, only slightly. Some cohorts, like Middle Eastern, black, and other, are almost entirely students of faith.

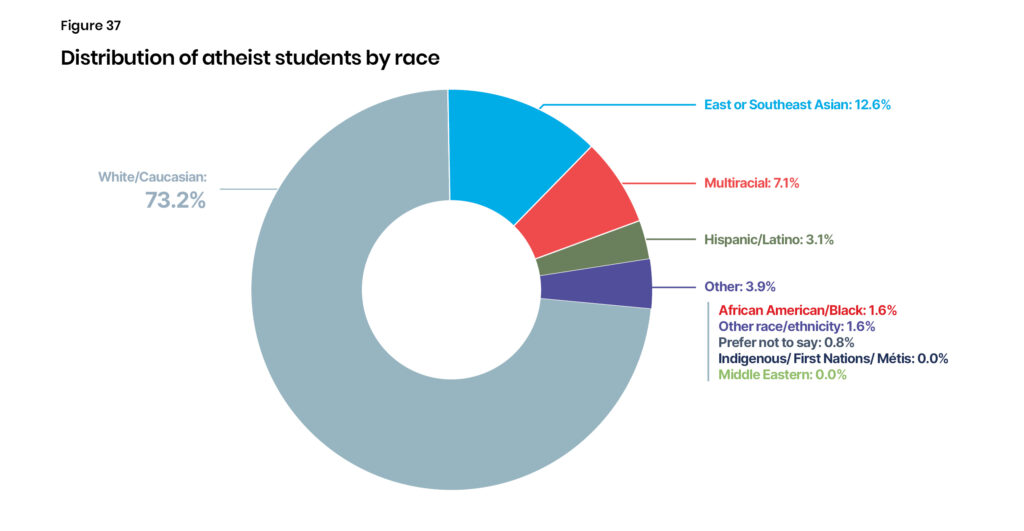

Conversely, atheist students are overwhelmingly white—three in four (Figure 37). When taken together and averaged out, an atheist student is 53.5 percent more likely to be white. No indigenous or Middle Eastern students, and a mere 1.6 percent of black students, in our sample are atheists.

In other words, the freedom of expression that atheists experience on campus—compared to religious students—is a mostly “white privilege,” to borrow the expression.

Figure 38 gives a more fulsome breakdown of religion by ethnic cohort. Bucketing agnostic and atheist together, the secular share rises considerably in most cohorts. And yet the fact remains: the overwhelming majority of visible minorities are religious, and atheists are three-quarters white.

Note:

- Of the 50 students who fall under the East or Southeast Asian and “Other religion” segment, they self-identify as follows: 16 Muslim (32%), 13 Hindu (26%), 13 “Other religion” (26%), and 8 Buddhist (16%).

- Of the 16 students who are in the Middle Eastern and “Other religion” segment, 12 are Muslim (75%), 2 Jewish (12.5%), and 2 Buddhist (12.5%).

- Of the 60 students who fall under the “Other religion” and “Other race/ethnicity” segment, they self-identify as follows: 26 Muslim (43.3%), 11 Jewish (18.3%), 10 Hindu (16.7%), 10 Sikh (16.7%), and 3 Other (5%).

- Of all 84 students under “Other race/ethnicity,” 35 identify as South Asian (41.7%).

Three themes emerge that warrant further unpacking—beyond the raw data and quantitative analysis.

The majority fear honest discourse

The data reveal that the students most comfortable sharing their views at Canadian universities identify as follows: liberal, secular, racialized, homosexual, gender-nonconforming. Merely 0.4 percent—less than half of 1 percent—of students match all five. Moreover, each particularity in isolation excludes the majority of students. Of all students: 37 percent identify as politically liberal. One-third are either agnostic or atheist. Non-whites are a minority. Less than one-third of students identify as not heterosexual, and 6 percent are gender nonconforming.

To summarize, on each controversial issue, the majority of students are uncomfortable—often very reluctant—thinking through their views out loud. Fully 99.6 percent of university students fall outside at least one of these particularities, and nearly one out of every five students does not fit inside any of them. When and where a student does not fit into one of these labels, it is all but guaranteed that they do not feel comfortable expressing themselves. This is dangerous.

In an atmosphere where disagreeable speech is considered violence, no one is safe. Ironically, the findings seem to indicate that the “safe space” culture on university campuses has created an environment where everyone fears misspeaking, for dread of being “cancelled.” And without freedom to speak and debate, the parallel danger is that universities are increasingly devoid of free thought. Research and intellectual progress will suffer—and be stymied if not thwarted.

Inadvertently, universities are silencing learning. Although a confluence of factors contributes to academic outcomes, surely self-censorship leads to decline. How can one learn, if they are discouraged from working through and processing information? How can a subject be mastered if respectful debate and robust discussion of competing viewpoints is frowned upon? How will knowledge increase, if exposure to new ideas and creative thinking and challenging the status quo are suppressed?

New discrimination does not solve old discrimination

University should be challenging, but students should not fear being treated badly or unfairly for expressing their viewpoints in a respectful manner. Efforts to minimize bias and the severity and prevalence of discrimination, however, need to be grounded in reality. Prejudice and bullying can never be entirely rooted out, as no amount of policing can extinguish bigotry outright. Perfection is not only an unreal expectation but a false standard that results in painful unintended consequences. And, therefore, it is a mistake to overcompensate in the form of discriminating against one set of students in the name of defending another cohort. Such tribalism is antithetical to a community of learning and research.

The challenges go much deeper than self-censorship and a lack of free speech but also include “soft” discrimination and threats to the fundamental rights (e.g. freedom of association) of those outside the circle of acceptable views. One example of many is the recent political controversy at UBC Okanagan.

The student union rejected a student application to found a Conservative Party Club, because of “concerns…regarding the political stance of the party your club would represent.” Their statement effectively captures the climate on campus: Because of “[our] commitment to inclusivity and respectful discourse,” capital-c Conservative partisanship will not be tolerated, as it “could make students…feel excluded or unwelcome.”v This is a timely example of what our data confirms: politically conservative and libertarian views are not welcome on campus.

The UBC Okanagan student union elaborated further concern for “Black and LGBTQ+ communities.” The pairing of these two communities together is ironic. Black students do not feel free to express their views on gender and sexuality, as, on these two issues, they do not conform to the zeitgeist. The probability of a randomly selected black student identifying as a member of the LGBTQ+ community is close to zero.

Thankfully, the university stepped in. The student union—despite claiming the decision was final and not open to appeal—reversed their decision, and now the Okanagan Conservative Club exists. The partisanship should be irrelevant. But, sadly, this episode is unsurprising, as it accurately reflects the political climate on Canadian campuses.

This is but one of many examples where a set of students—for no fault of their own—are mistreated, in the name of concern for another set of students. Rather than attempt to treat all alike, only the in-favour groups are treated well, while those out of favour—often the majority—are marginalized.

The bandwagon effect likely overstates the “preferred five”

Given such hostilities, it is likely that the five particularities that garner preferential treatment are overstated. Individuals can only handle so much adversity. So, if a student is mistreated for being a female and for being a Jew and for her sexual orientation, it makes sense that she would tend to align with the “in” political group—if only as a defence mechanism. Conversely, an agnostic, straight male is extremely unlikely to face outright mistreatment for any of those particularities, so he is considerably more willing to express a political position outside the mainstream. Hence, the over-representation of his demographic amongst libertarians.

Bottom line: If the prevailing winds change, each of the “preferred five” will experience an outsized decline, as a disproportionate share hold that particularity out of expediency (i.e. they are not “true believers”).

Therefore, policy makers should not fear the inevitable backlash that will emerge from introducing policies that promote open inquiry, merit, and genuine debate in university classrooms.

In conclusion, free expression on campus is far from robust. On non-controversial issues, 93.4 percent of university students are comfortable speaking up and giving their views in a university classroom. This comfort level drops precipitously, however, on controversial issues (Figure 39). While it appears—at first glance—that the majority of students are at least somewhat comfortable sharing their views on all issues, it can be appreciated, upon analysis, that this comfort does not come from a place of openness to new perspectives and furthering knowledge, but the opposite.

Whether or not a student feels free to speak up in a class discussion is largely based on whether they identify with one of five favoured groups or ideologies: politically liberal, religiously non-religious, ethnically racialized, and neither heterosexual nor gender-conforming. Where a student aligns with these preferentially-treated identities or ideologies, they are almost certainly “very comfortable” sharing their views; where they are not aligned, it is much less likely that they are comfortable being honest.

Only 0.4 percent of students identify as all five preferential particularities, and thus, it is a mistake to assume that the majority of students are comfortable thinking out loud. The reality is that for the 99.6 percent of university students who do not identify with at least one of them—and the nearly one in five students who identify with none of the preferred five—there is a high probability that they are reluctant to openly discuss their views on at least one issue, for fear of bad or unfair treatment.

Please see PDF for appendices.

The authors would like to publicly express their deep gratitude for the generous participation of all the students who completed the survey, making this study possible.

Please see PDF for references.

David Hunt, MPP, BBA, is the research director at the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. His work has been presented at numerous conferences and to various levels of government, cited in major media, and used as evidence in court. Hunt holds a Master of Public Policy from Simon Fraser University and a Bachelor of Business Administration (with distinction) from Kwantlen Polytechnic University, where he was the Dean’s Medal recipient.

Martin Mrazik, PhD, R.Psych., MEd, BSc, is a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, a registered clinical neuropsychologist, and professor in the educational psychology department of the University of Alberta Faculty of Education.

Misheel Batkhuu is a research intern at the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. Batkhuu is majoring in data science and finance at the University of Toronto in pursuit of a Bachelor of Business Administration (Honours).

About the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy

Who we are

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new education and public policy think tank that aims to renew a civil, common-sense approach to public discourse and public policy in Canada.

Our vision

A Canada where the sacrifices and successes of past generations are cherished and built upon; where citizens value each other for their character and merit; and where open inquiry and free expression are prized as the best path to a flourishing future for all.

Our mission

We champion reason, democracy, and civilization so that all can participate in a free, flourishing Canada.

Our theory of change: Canada’s idea culture is critical

Ideas—what people believe—come first in any change for ill or good. We will challenge ideas and policies where they are in error, and buttress ideas anchored in reality and excellence.

Donations

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity and all donations will receive a tax receipt. To maintain our independence, we do not seek nor will we accept government funding. Donations can be made at www.aristotlefoundation.org.

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy has internal policies to ensure research is empirical, scholarly, ethical, rigorous, honest, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge and the creation, application, and refinement of knowledge about public policy. Our staff, research fellows, and scholars develop their research in collaboration with the Aristotle Foundation’s staff and research director. Fact sheets, studies, and indices are all peer-reviewed. Subject to critical peer review, authors are responsible for their work and conclusions. The conclusions and views of scholars do not necessarily reflect those of the Board of Directors, donors, or staff.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER