This study summarizes the key facts on slavery in Canada, from the colonial period to slavery’s eradication in British Columbia over four centuries later.

In early Canada, indigenous slave-trading networks were robust:

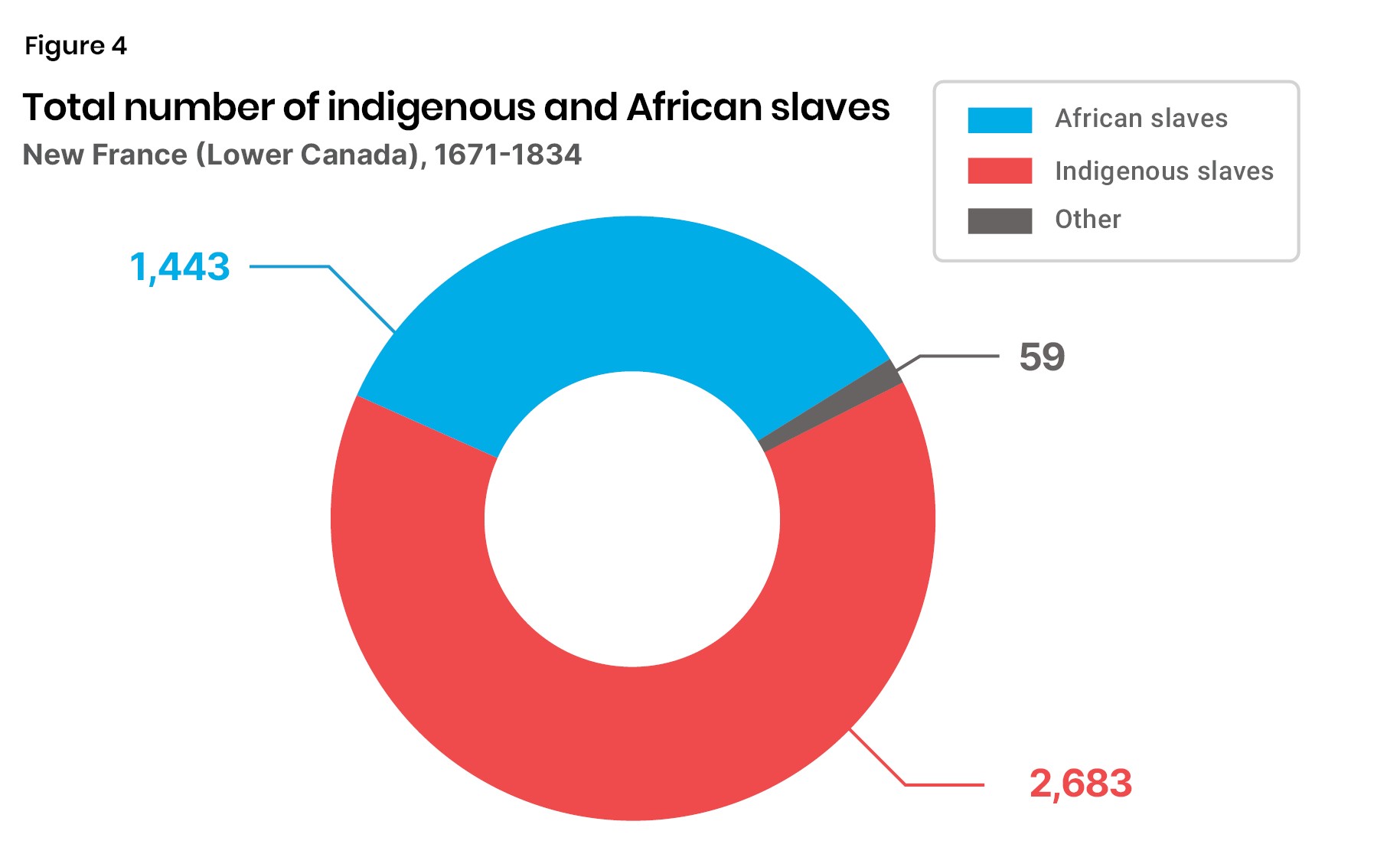

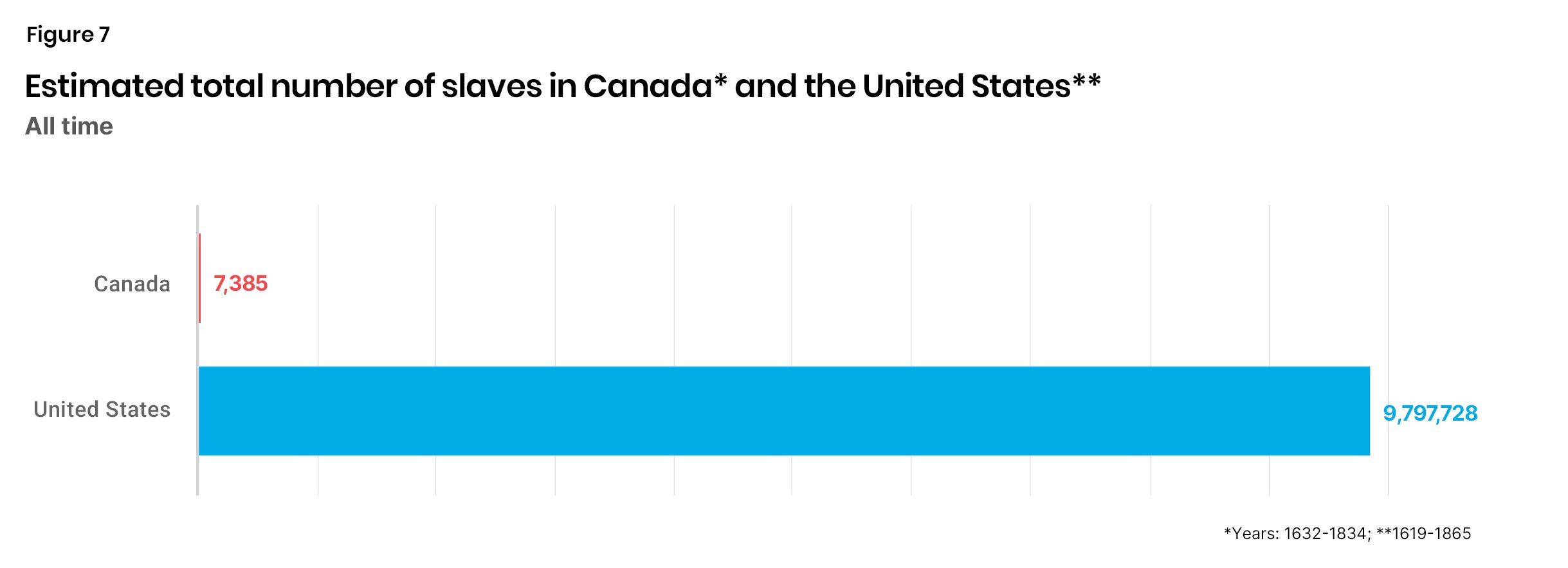

Thus, it makes sense that about 64 percent of all the slaves held by Europeans in New France from the mid-17th century to 1834 (when slavery was fully abolished in the British Empire) were indigenous; 34.5 percent were African. Using the upper estimates of historians, the grand total of all slaves held in Canada across that period numbered 7,000 to 7,500. For comparison, more than thirteen hundred times that many souls—nearly 10,000,000—were enslaved from 1619-1865 in the United States.

Despite opposition from slave-owning legislators, Upper Canada passed the first legislation in the British Empire to end slavery—15 years before Britain outlawed the slave trade, 41 years before Britain abolished slavery in the West Indies, and 72 years before the States settled the issue on the battlefield. Thus, if by “Canada” we mean the country confederated in 1867, the fact is that slavery has never been legal here; all legal Canadian slavery was pre-Confederation.

Moreover, Canada welcomed over 30,000 African-Americans who escaped slavery and found freedom at the northern terminus of the Underground Railroad.

Yet, indigenous slavery was not fully stamped out in British Columbia until near the turn of the 20th century. And human trafficking remains a grave evil facing Canadian society today.

On balance, Canada’s history and record on slavery deserve to be cherished and celebrated.

For the past several decades, schools, universities, media, and even governments have taken upon themselves the moral duty of shocking Canadians with the “news” that early European settlers—in what are now Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes—owned and traded slaves. Of course, there is nothing shocking or newsworthy about this fact: slavery, sadly, has been a norm throughout much of the world for much of history.

Slavery was practised in Canada. But the facts shape a different perspective than the “white guilt” narrative espoused today. The record offers more than a few surprises.

Given inevitable pushback, it is critical to first draw attention to what is beyond the scope of this short paper. This study will not examine the estimated 27.6 million victims of human trafficking alive today,1 of whom there are many in Canada. (The RCMP estimates between 700,000 to four million people, annually, are trafficked around the world.2) Nor is this a study of the neglected history of pre-modern anti-slavery movements, such as the Essene and Therapeutae sects in ancient Israel, which prohibited slavery, and early Christian leaders like Queen Bathilde, a former slave who worked to abolish slavery in her 7th century Frankish kingdom.

This study offers a short summary of the key facts on slavery in Canada, from the arrival of Europeans to slavery’s eradication in British Columbia over four centuries later. It begins with a pre-Canadian understanding of the issue, then explores the wretched practice across Canada—from the east coast to west coast, from indigenous trade networks deep in North America’s heartland to transatlantic trade networks, and quite a bit in-between.

One of the earliest poems on record, the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, makes reference to slavery:

He is king, he does whatever he wants,

takes the son from his father and crushes him,

takes the girl from her mother and uses her.

These ancient verses offer a vivid image of the cruelty of slavery, a practice that was universal—adopted by great empires and nomadic peoples alike. One of the most infamous examples is the transatlantic slave trade out of Africa.

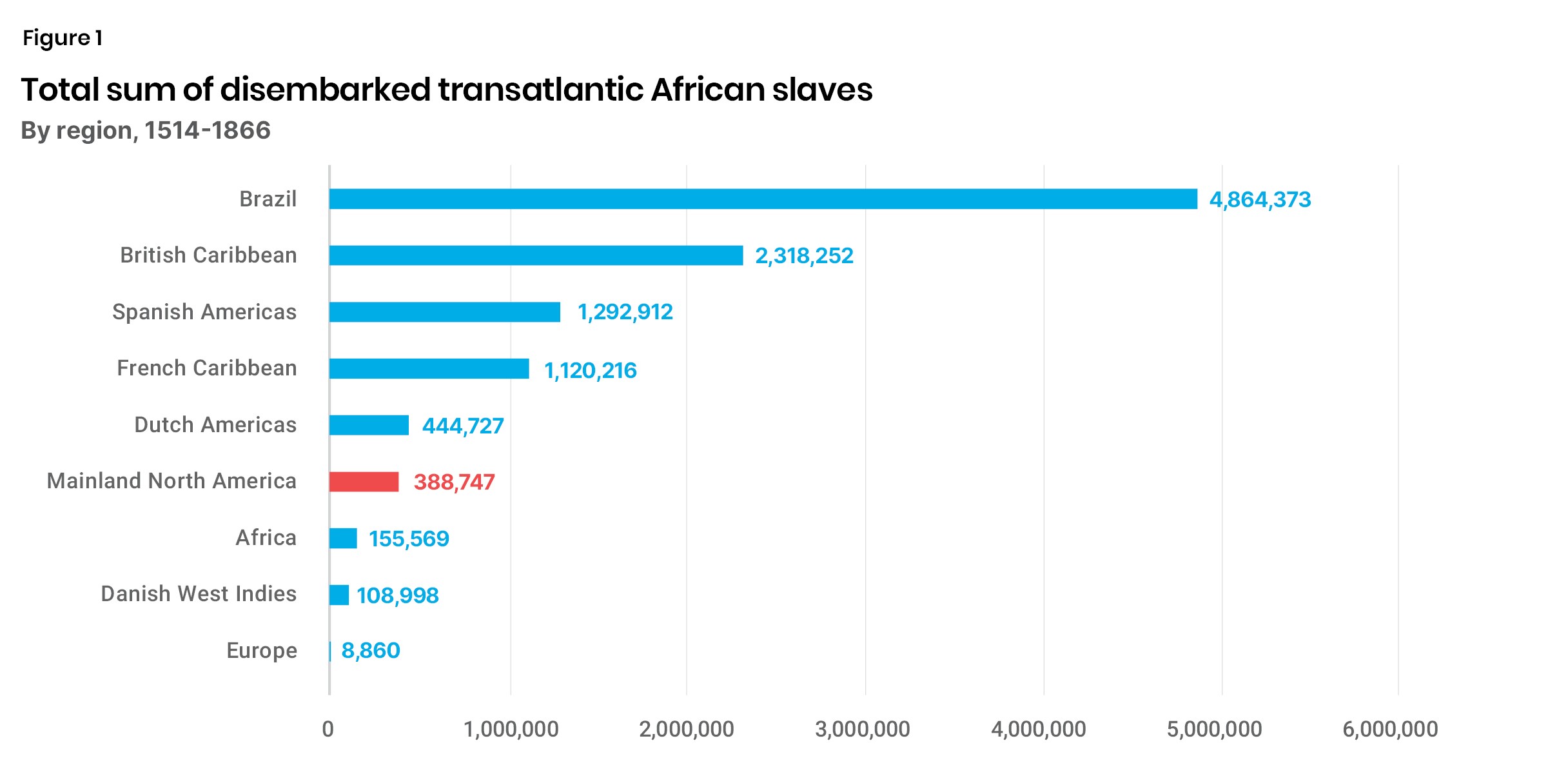

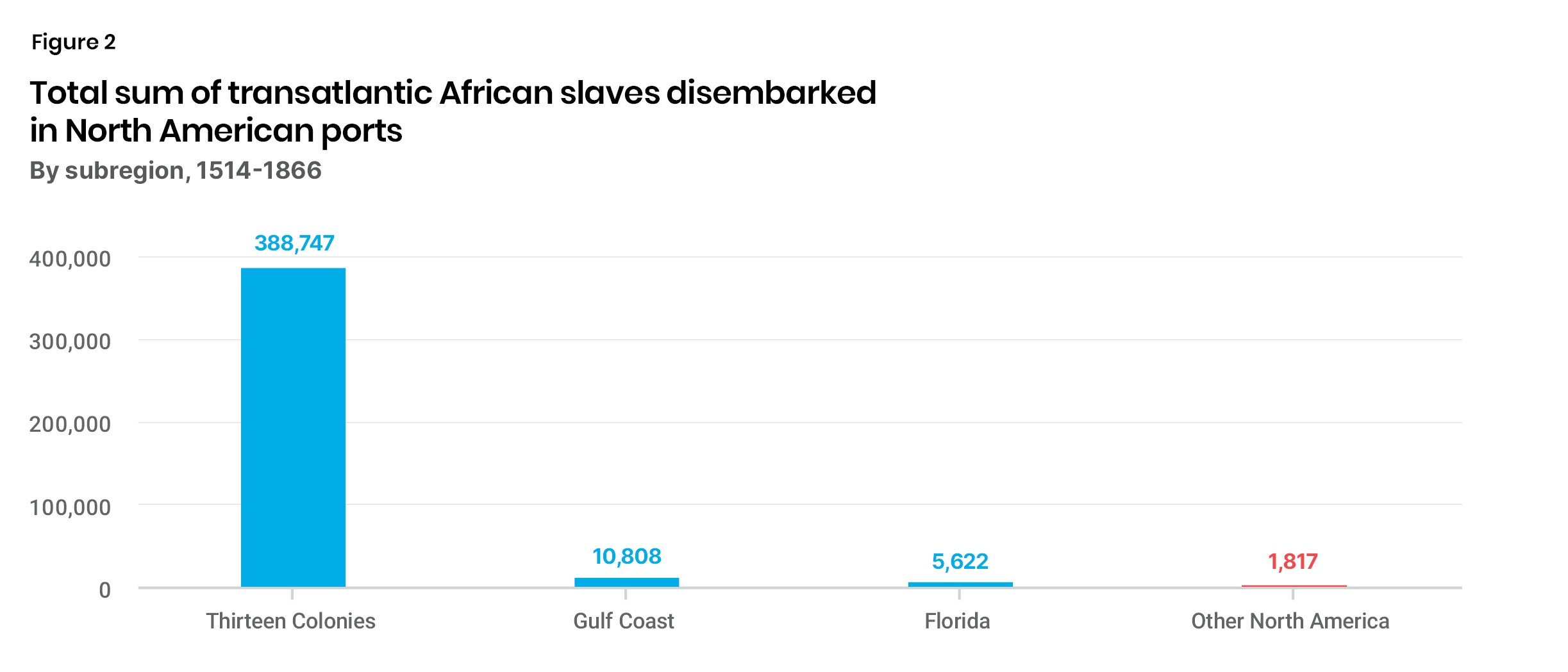

From the first transatlantic shipment to the year before Confederation, 1514 to 1866, respectively, data exists for more than 36,000 transatlantic African slave voyages. Based on these records, an estimated 388,747 African slaves disembarked on the North America mainland (Figure 1). No Canadian ports or regions are identified, but 1,817 of these slaves disembarked in “Other North America” (Figure 2).3

Source: Slave Voyages, 1501-18664

Source: Slave Voyages, 1501-18665

The number of these souls and/or their enslaved descendants that made their way to what is now Canada is explored below. But a lesser-known history—that of indigenous slavery—is explored first.

In pre-Columbian North America there were at least 39 distinct indigenous slave societies.6 One early account of slavery in present-day Canada comes from John Gyles, whose family had settled near today’s Pemaquid Falls, New Brunswick. In August of 1689, while some settlers were bringing in the harvest, they were attacked by thirty to forty Maliseet natives. Young John, together with several members of his family, was captured. His 1735 Memoirs of Odd Adventures, Strange Deliverances, etc., in the Captivity of John Gyles, tells the story of his father’s death, his brother’s escape, and the brutal treatment he witnessed: “A captive among the Indians is exposed to all manner of abuses and to the extremest torture, unless their master, or some of their master’s relations, lays down a ransom; such as a bag of corn,” he writes. Gyles describes torture by an old native woman, who “will take up a shovel of hot embers and throw them into a captive’s bosom. If he cry out, the Indians will laugh and shout, and say, ‘What a brave action our old grandmother has done.’ Sometimes they torture them with whips, &c.”7

Gyles’s account of the treatment of captives was not atypical. Captives could be killed immediately, tortured by clan members and then killed, adopted into the tribe (often to replace a clan member who had been killed in a previous war), or enslaved, but neither adopted nor assimilated—so left in a state of limbo.8 As in Gyles’s case, an older woman would determine the victim’s fate.9

Among the Iroquois of New France, and in today’s Ontario, frequent warfare and epidemics reduced the population in the 17th century. Mourning raids to acquire captives relieved grief, avenged the deaths of relatives, and replenished the population.

The presence of Europeans in the Northeast exacerbated population loss in two ways: through epidemics, and by increasing the amount of warfare to meet the demands of the fur trade.10 As numbers in a given tribe plummeted, raiding for captives surged, and some peoples were wiped out. Captives who were not tortured or killed might instead be adopted into a family to replace dead relatives. These adoptees would then supply the labour for agriculture, for domestic chores, and for paddling canoes.11

Historians are best informed about the conflict between the Iroquois and the Huron, but the pattern of raiding for captives leading to extinction is typical. By the 1660s, the Iroquois-Huron wars ended with “the virtual destruction of the Huron and their disappearance as an independent people.”12 By the late 17th century, up to two-thirds of the population of some Iroquois communities consisted of adoptees—that is, captives. This resulted in an interpenetration of cultures.13

Not all the captives were indigenous; Europeans figured among them, and some adapted so well that they refused to leave. Among those who were freed, some even wrote “captivity narratives,” like John Gyles’s, opening a window into the ways of life of indigenous peoples in Canada.

Scholars debate whether adoptees should be considered slaves or not, since many assimilated into their new communities. If we accept the definition of slavery advanced by scholar Orlando Patterson, that slavery is defined not by ownership but by “natal alienation” from one’s birth community, then these were enslaved people.14

That it was not Europeans who introduced slavery to Canada should come as no surprise. Scholars of world slavery have long demonstrated that, since ancient times, warfare and slavery have worked in tandem—and warfare was universal. For male captives, the only reprieve from death was enslavement; for women, it was domestic, agricultural, or sexual servitude.

The system of native alliances engaged in trading slaves to the colonists of New France from 1660 to 1760 was “the most far-reaching” in North America.15 It extended deep into the American Midwest: from the Missouri River basin to the St. Lawrence River Valley, and from the Upper Mississippi Valley to the western Great Lakes (Figure 3). The Iroquois traded captives from the Chesapeake to Lake Michigan, and in 1669 a Sulpician missionary reported that he had met a Nipissing chief who “had a slave the Ottawas had presented to him . . . from a very remote nation in the southwest.”16

Source: Publisher’s renderings based on Rushforth (2003) and Bessiere (n.d.).17

This sprawling network of trade routes, largely run by indigenous traders, resembles the network of indigenous trade routes that delivered African captives to European slave traders waiting on the Slave Coast of West Africa from the mid-17th century until Britain shut it down. Change “African” to “indigenous” and “New World” to “New France,” and the acute observation of eminent African-American slavery scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. applies as well to the indigenous-French slave trade as to the transatlantic trade: “The sad truth is that without complex business partnerships between African elites and European traders and commercial agents, the slave trade to the New World would have been impossible, at least on the scale it occurred.”18 Both sides bear responsibility.

The indigenous peoples traded with French traders, but they had divergent perspectives on the purpose of trading captives. Just as the natives often offered captives as gifts to opposing tribes to cement truces or affirm alliances, they viewed the offers of captives to their French trading partners as “powerful symbols of their emerging partnership.” This is something that took some time for the French, who initially balked at or misunderstood these captive exchanges, to understand. However, as an increasing number of captive exchanges occurred, especially after the “Great Peace of 1701,” more families in New France began to purchase them.19 By 1725, in Montreal’s commercial district, “fully half of all colonists who owned a home . . . also owned an Indian slave.” Proportionately, though, the number of slaves “never constituted more than 5 percent of the colony’s population.” These slaves did domestic work, farmed, loaded, and unloaded at the docks, and worked in mills and as “semi-skilled hands in urban trades.”20 There were some black slaves, but the number was small.

What fuelled the market for slaves in the colony was a labour shortage, leading intendant Jacques Raudon to proclaim in 1709 “that all the Panis [indigenous slaves] and Negroes who have been bought, and who shall be purchased hereafter, shall belong in full proprietorship to those who have purchased them as their slaves,” thus formally legalizing slavery in the colony.21

Quebec historian Marcel Trudel came up with a figure in 1960 for the number of slaves in New France (later, Lower Canada): Aggregating all the slaves, black and panis, from the mid-17th century to 1834, when slavery was abolished in the British Empire, it totalled 4,185, with 65 percent indigenous and 35 percent African (Figure 4).22 With no need for plantation-style gang labour, slavery tended to be domestic.23

Source: Trudel

Indigenous slavery was no more benign on Canada’s west coast. Among the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest, slavery was particularly brutal, as bondage was lifelong and hereditary; masters held complete control over even life and death.24

For example, in March of 1803, the English ship the Boston anchored in an inlet of Nootka Sound in British Columbia. On the morning of March 13, according to an account by the twenty-year-old ship’s armourer, John R. Jewitt, “several of the natives came on board in a canoe from the village of Nootka with their king, called Maquinna, who appeared much pleased on seeing us and, with great seeming cordiality, welcomed Captain Salter and his officers to his country.”25 Ten days later, however, Maquinna’s men massacred all the crew except Jewitt and the sailmaker, who were preserved for their artisanal skills. They escaped two years later.

Contrary to a popular image of native cultures as egalitarian, the structure of the west coast native communities was highly stratified, with three classes: title holders, commoners, and slaves (ranging between 5 and 25 percent of a village); only the title holders could own slaves, so slaveholding signalled high status. Most war captives were enslaved, and the owner retained the power of life and death over his booty.26 At a potlatch or the ceremony for completion of a home, slaves were killed with a special club, called a “slave killer.”27 They were also sacrificed at funeral feasts as an indication of the wealth of the heir, and to provide labour to the spirit of the dead in the afterlife.28 Tribes of the Plateau region (between the Rockies and the Coastal Range) similarly attacked each other in quest of captives, later assimilating females into their communities, where their children were not considered to be slaves.29

In the first third of the 19th century, the slave trade network centred on the Pacific Coast and the Columbia River, with only minimal involvement of Europeans. There was also an inland demand for slaves by native people, supplied by coastal native middlemen, in exchange for furs; it has been suggested that significant population loss from smallpox upped the demand for slave labour. As historian Leland Donald explains, “A cycle of raids for slaves, trade of slaves for furs, and trade for furs to Euroamericans became part of the rivalry between important titleholders.”30

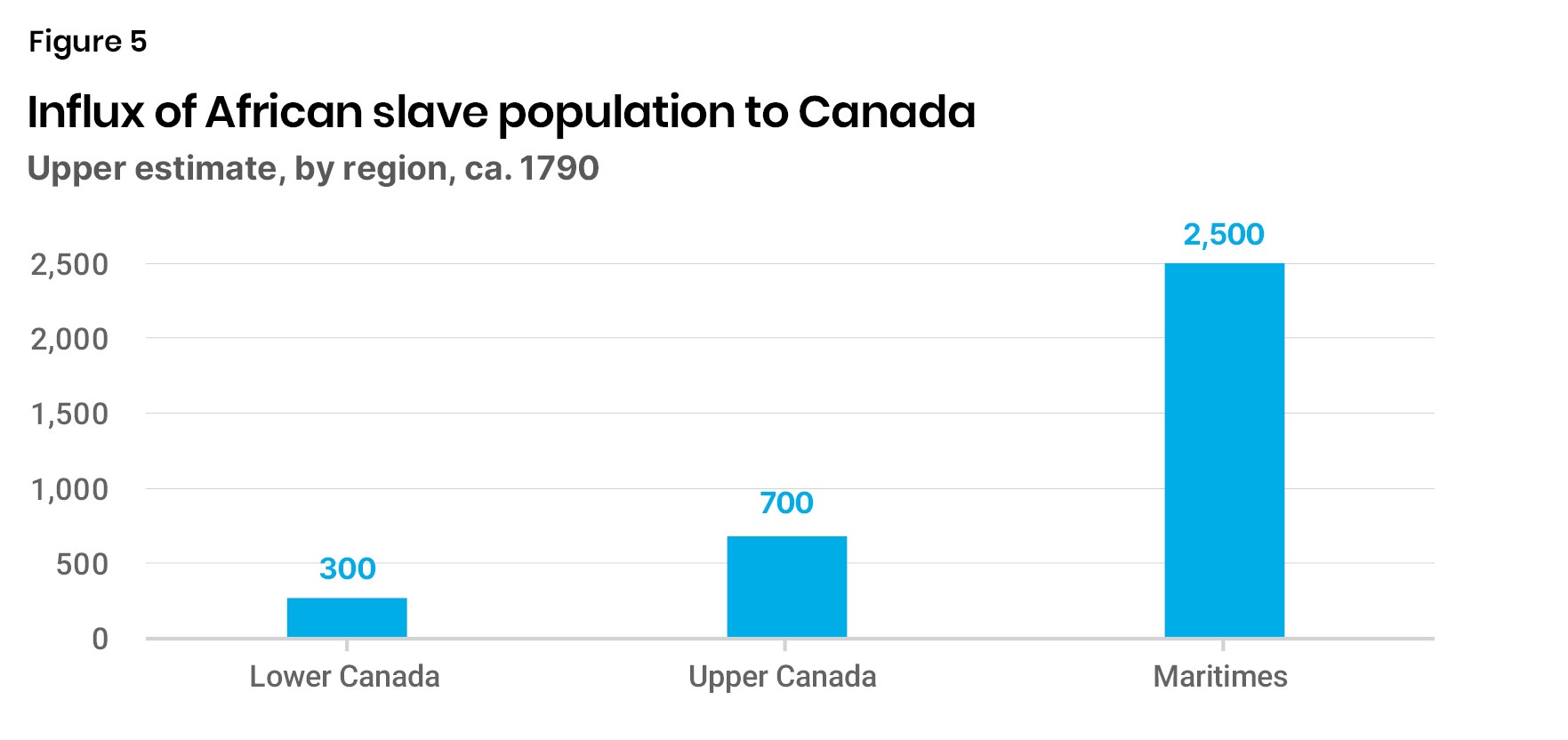

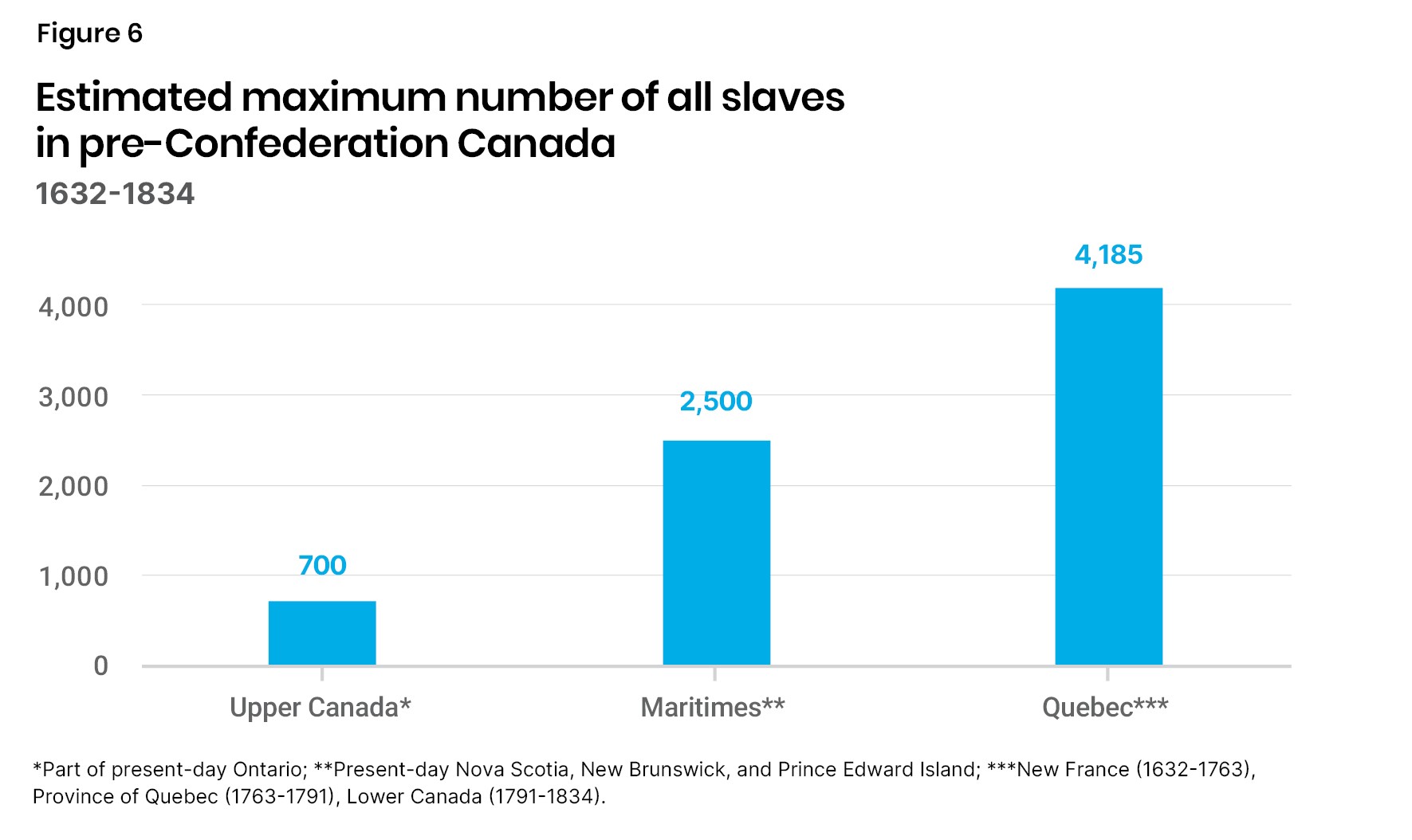

In the wake of the American War of Independence (1775-1783), the slave population of British North America grew. To encourage Loyalist immigration, Britain’s Parliament passed the Imperial Statute of 1790, permitting settlers to bring in “negros [sic], household furniture, utensils of husbandry, or cloathing [sic],” which could not be sold for one year after arrival. The influx totalled at most 3,500—approximately 1,200-2,500 to the Maritimes, 300 to Lower Canada (Quebec), and 500-700 to Upper Canada (Ontario) (Figure 5).31 As with New France, agriculture in Upper Canada was not suited to gang labour, so the number of slaves held by individuals was not high; twenty was considered a lot. Most slaves worked as domestics or in their owners’ businesses (for example, as blacksmiths or carpenters). Some escaped to free states in the United States.

Source: Henry-Dixon (2016)

In total, across two centuries, the estimated number of slaves in pre-Confederation Canada amounted to approximately 7,385 (Figure 6). Conversely, nearly 10 million souls were enslaved in the United States from 1619-1865; the contrast is extreme (Figure 7). In one census alone—on the eve of their Civil War—the US recorded 3,953,760 American slaves in 1860.32

Source: Author’s calculations based on Trudel (2013), Winks (2021), and Henry-Dixon (2016)

Source: Author’s calculations based on Hacker (2020), Trudel (2013), Winks (2021), and Henry-Dixon (2016)

In addition to the slaves of early English or American settlers and those imported by Loyalists to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island (PEI), approximately 3,000 freed blacks, known as “black Loyalists,” migrated to Nova Scotia (which included New Brunswick at the time) following the War of Independence. They had earned their freedom under the terms of Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation of 1775, which guaranteed emancipation to slaves who deserted their masters to fight for the British. Life was not easy for these settlers, who faced discrimination over land grants and hostility from their white counterparts. For instance, an angry white mob drove blacks out of Birchtown, where they had settled. In 1790, about 1,000 disenchanted black Loyalists opted to take a chance on the quixotic expedition organized by idealistic British abolitionists to settle in Sierra Leone on Africa’s west coast. Still, with increasing interaction in Nova Scotia between slaves and free blacks, it was becoming easier for slaves to escape their masters, and many did.

In the 1770s, the moral sensibility of the British public was undergoing a sea change, thanks to abolitionist activism. The modern abolition movement focused initially on prohibiting the sale and purchase of slaves, then moved gradually towards banning any slave ownership. In short order, abolitionism spread to the colonies.

Between 1791 and 1808, as antislavery sentiment in Britain grew, two successive Chief Justices in Nova Scotia, Thomas Strange and Sampson Blowers, denied slave owners the right to reclaim their slaves without proof of ownership.33 Such opposition by the courts, which signalled to owners the economic liability of slave ownership, allowed slavery in Nova Scotia to wither away, as it did gradually in New Brunswick and PEI as well.34

In Upper Canada, government officials, like Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe, advocated abolition. Though keen to increase the population of British North America, Simcoe knew this meant an influx of slaves with the Loyalists. He initially resolved not to accept any law that “discriminates by dishonest policy between the natives of Africa, America or Europe,” but was hamstrung in its implementation by a legislative council that included many slave owners.

Then came the case of Chloe Cooley, a black woman from Queenston, Upper Canada, cruelly abducted by her owner to be sold down the Niagara River into American slavery. This distressing story inspired Simcoe to introduce the first antislavery legislation in the British Empire, the Act to Limit Slavery in Upper Canada (1793). To ensure its passage through the Legislative Assembly (with its six slave-owning members), the terms of the Act were gradual:

As this legislation made retaining slaves economically disadvantageous, slavery in Upper Canada gradually petered out.

Two other significant legal moves followed the new law. In 1819, Attorney General John Beverley Robinson of Upper Canada tendered the opinion that, in light of British precedent, black fugitives are free. Ten years later, Lieutenant Governor Sir John Colborne made his antislavery position clear to visiting American black leaders from Cincinnati: “Tell the Republicans on your side of the line that we royalists do not know men by their color. Should you come to us you will be entitled to all the privileges of the rest of His Majesty’s subjects.”35 Thus, the British-Canadian attitude toward slavery stood in stark contrast to the American.

In the decades before the American Civil War, Canada offered safe haven to approximately 30,000 African-American refugees, propelled north by a desire for freedom and especially by the two Fugitive Slave Acts (1793 and 1850). Another inducement was the stories soldiers returning from the War of 1812 told of how blacks lived freely north of the border.

Refugees, with some help from sympathetic white abolitionists, established several black communities in Upper Canada—the final stop on the Underground Railroad to freedom. One of these, the Dawn settlement (later Dresden, Ontario), became the home of fugitive Josiah Henson, on whose life Harriet Beecher Stowe based her central character in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The most successful of these settlements was Buxton, established in 1849. Its founder, Reverend William King, insisted on communal self-reliance. Black abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass touted Buxton as “one of the most striking, convincing, and gratifying pieces of evidence that black men can live, and live well, without a master.”36

Among the black abolitionists attracted to Canada were several prominent figures:

Henry Bibb fled to Detroit from Kentucky in 1842, then to Sandwich in Canada West. He organized conventions of fugitives in 1850 and 1851 and established an abolitionist newspaper, Voice of the Fugitive.

Mary Ann Shadd, the first black woman newspaper editor in North America, produced a competing paper, The Provincial Freeman; she disagreed with Bibb on one of the central ideological issues of the time, touting self-reliance over “begging” (reliance on philanthropic aid).

The indomitable Harriet Tubman escorted more than 60 people to freedom in St. Catharines, Ontario, where she settled her family. It was in Canada that she met antislavery militant John Brown, who dubbed her “General Tubman.”

American abolitionist Benjamin Drew interviewed freed slaves in Canada, compiling their accounts in A North-Side View of Slavery. The Refugee: or the Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada, Narrated by Themselves, With an Account of the History and Condition of the Colored Population of Upper Canada37. Drew paints a picture of comfort and inclusion (which is not to say that refugees did not encounter prejudice and resistance to their presence in some quarters):

Many of the colored people own the houses in which they dwell, and some have acquired valuable estates. No distinction exists in Toronto, in regard to school privileges. One of the students in the Normal School was a fugitive slave, and colored youths are attending lectures in the University. . . . They are excluded . . . from none of the churches, and in all of them a few of the African race may be found.

He also includes accounts from freed slaves he interviewed:

Henry Williamson, of Hamilton, Upper Canada, wrote:

Contrasting what I feel now and what I was in the South, I feel as if a weight were off me. Nothing would induce me to go back, —nothing would carry me back. I would rather be wholly poor and be free, than to have all I could wish and be a slave. I am now in a good situation and doing well, —I am learning to write.”

Mrs. Christopher Hamilton of London, Canada West [Upper Canada], offers equally stirring words about the freedom she found in Canada:

I left Mississippi about fourteen years ago. I was raised a house servant, and was well used,—but I saw and heard a great deal of the cruelty of slavery. I saw more than I wanted to—I never want to see so much again. . . I had rather live in Canada, one potato a day, than to live in the South with all the wealth they have got. I am now my own mistress, and need not work when I am sick. I can do my own thinkings, without having any one to think for me.38

The British Empire abolished slavery before Confederation, including in Her Majesty’s colonies and dominions of present-day Canada. Thus, if accusations of slavery are in reference to the modern country founded in 1867, one might assume such allegations are false. But slavery did exist in post-Confederation Canada—on the west coast.

Eradicating indigenous slavery in British Columbia proved difficult, despite the efforts of British (and later Canadian) officials. James Douglas, commander of Fort Vancouver, observed predatory slave raids by the Haida and tried to end the practice by moral suasion, denouncing it as a “detestable traffic.” But, he explained, he found “no remedy within our power” to do so, with white settlers outnumbered two to one by indigenous peoples.39

Two reports from the late 19th century—one by a missionary, the other by a naval officer—tell of ongoing slavery in the Pacific Northwest. Given the difficulty of imposing Canadian law from a distance, slavery in Canada was not extinguished until near the turn of the 20th century.40

Pre-Confederation Canada’s record on slavery was far from perfect, but in comparison with the rest of the world, it was progressive. Much of the credit for this rests on the colonies’ symbiotic relationship with Britain. Between the late 18th century and the early 19th, Britain’s free press saw a surge of antislavery pamphlets, petitions, and public speakers pushing Parliament towards abolition. This influenced key decision-makers in Canada, like Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe.

The contrast with the United States is striking: A forceful, organized abolition movement didn’t begin there until the 1830s, and northern abolitionists saw their newspapers and pamphlets banned and burned in southern states. Antislavery senator Charles Sumner was physically assaulted in Congress!

Nothing like this happened in Westminster or in Canadian legislatures. Over the objections of slave-owning legislators, Upper Canada passed the first legislation in the British Empire to end slavery—15 years before Britain ended the slave trade, 41 years before Britain ended slavery in the West Indies, and 72 years before the States settled the issue on the battlefield.

This is not to mention the vast difference in volume. The total number of all slaves ever recorded in Canada amounts to less than eight thousand. Conversely, in the US, around 10 million total Americans were bound in slavery.

Though black and indigenous Canadians would continue to face discrimination here, this country’s record on the slavery question stands up well to comparison with its closest neighbour—and with most other countries around the world. This history deserves to be remembered and our record lauded.

Please see PDF for references.

Marjorie Gann is a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, a retired elementary school teacher, and a children’s author. Her 1994 book, Discover Canada: New Brunswick (Grolier), surveyed the geography, history, economy, and culture of the province for young readers. Her history of world slavery, Five Thousand Years of Slavery (Tundra), co-authored with Janet Willen, was recognized as a 2012 Notable Book for a Global Society by the International Reading Association. Her book Speak a Word for Freedom: Women Against Slavery (Penguin Random House), also co-authored with Willen, was published in 2015. She sits on the executive of the Association of Jewish Libraries – Canada, and is an educational consultant and reviewer of children’s books for the Camera Education Institute (Committee for Accuracy in Middle East Reporting and Analysis).

About the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy

Who we are

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new education and public policy think tank that aims to renew a civil, common-sense approach to public discourse and public policy in Canada.

Our vision

A Canada where the sacrifices and successes of past generations are cherished and built upon; where citizens value each other for their character and merit; and where open inquiry and free expression are prized as the best path to a flourishing future for all.

Our mission

We champion reason, democracy, and civilization so that all can participate in a free, flourishing Canada.

Our theory of change: Canada’s idea culture is critical

Ideas—what people believe—come first in any change for ill or good. We will challenge ideas and policies where they are in error, and buttress ideas anchored in reality and excellence.

Donations

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity and all donations will receive a tax receipt. To maintain our independence, we do not seek nor will we accept government funding. Donations can be made at www.aristotlefoundation.org.

Research policy and independence

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy has internal policies to ensure research is empirical, scholarly, ethical, rigorous, honest, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge and the creation, application, and refinement of knowledge about public policy. Our staff, research fellows, and scholars develop their research in collaboration with the Aristotle Foundation’s staff and research director. Fact sheets, studies, and indices are all peer-reviewed. Subject to critical peer review, authors are responsible for their work and conclusions. The conclusions and views of scholars do not necessarily reflect those of the Board of Directors, donors, or staff.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER