Migration is a fact of human history, and migration to and from Canada is no exception. This report focuses on one aspect of immigration and Canada: its impact on the demand for housing. In summary:

As it applies to the demand for housing and the resulting adverse consequences, including rising rental costs and house prices, current high immigration rates—even after recently-announced reductions—now constitute too much of a “good thing.”

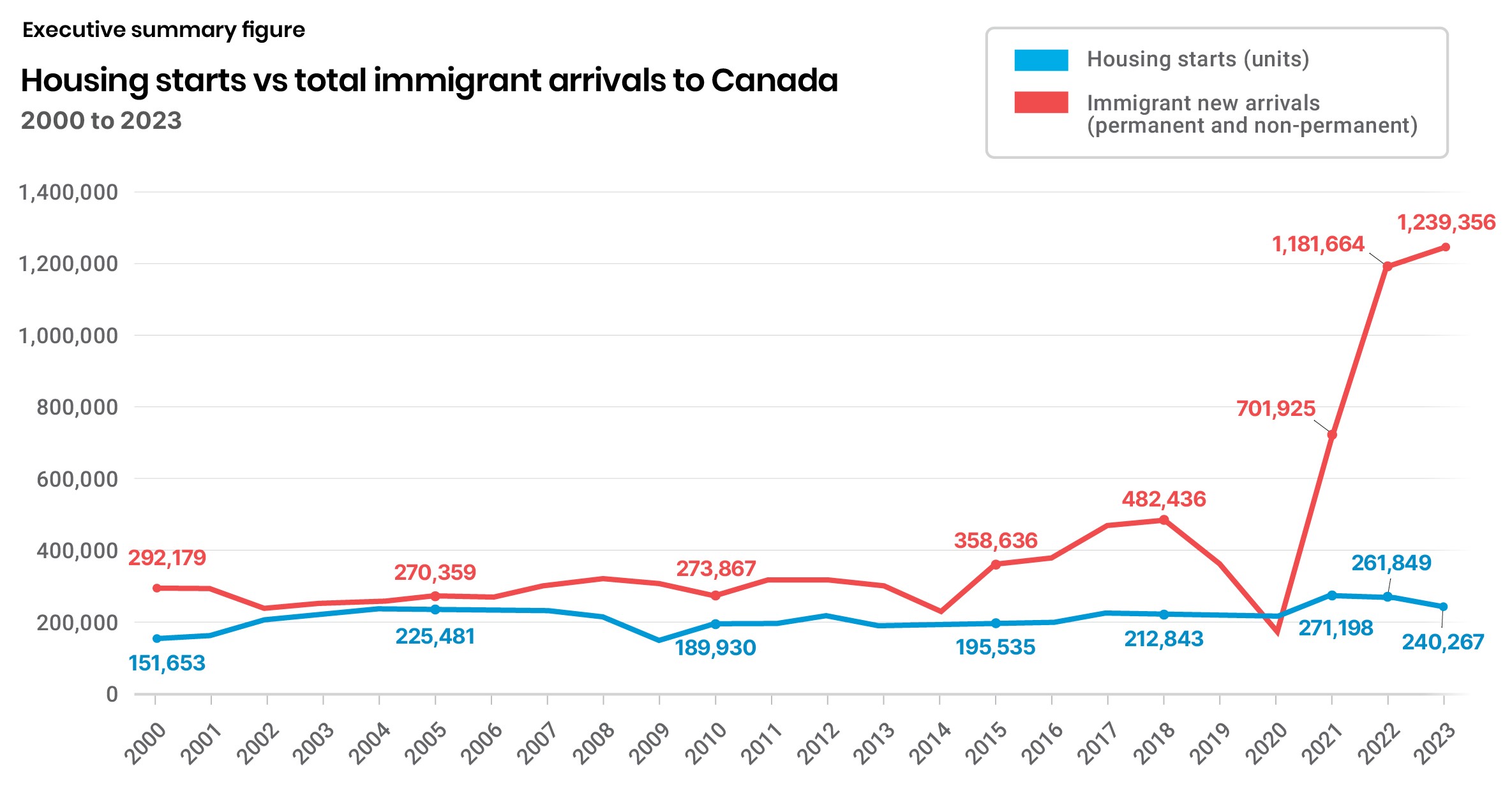

High immigration intake in multiple categories should be further reduced beyond recent federal government announcements. This is necessary as new housing supply has not, and cannot, be built rapidly enough to accommodate all arrivals—or even all existing Canadians. The data on housing completions and starts in recent years show there is no reason to expect that that reality will change in the foreseeable future. To moderate demand in the housing market and reduce the increasing pressure on rental costs, the levels of most varieties of immigration should be significantly reduced.

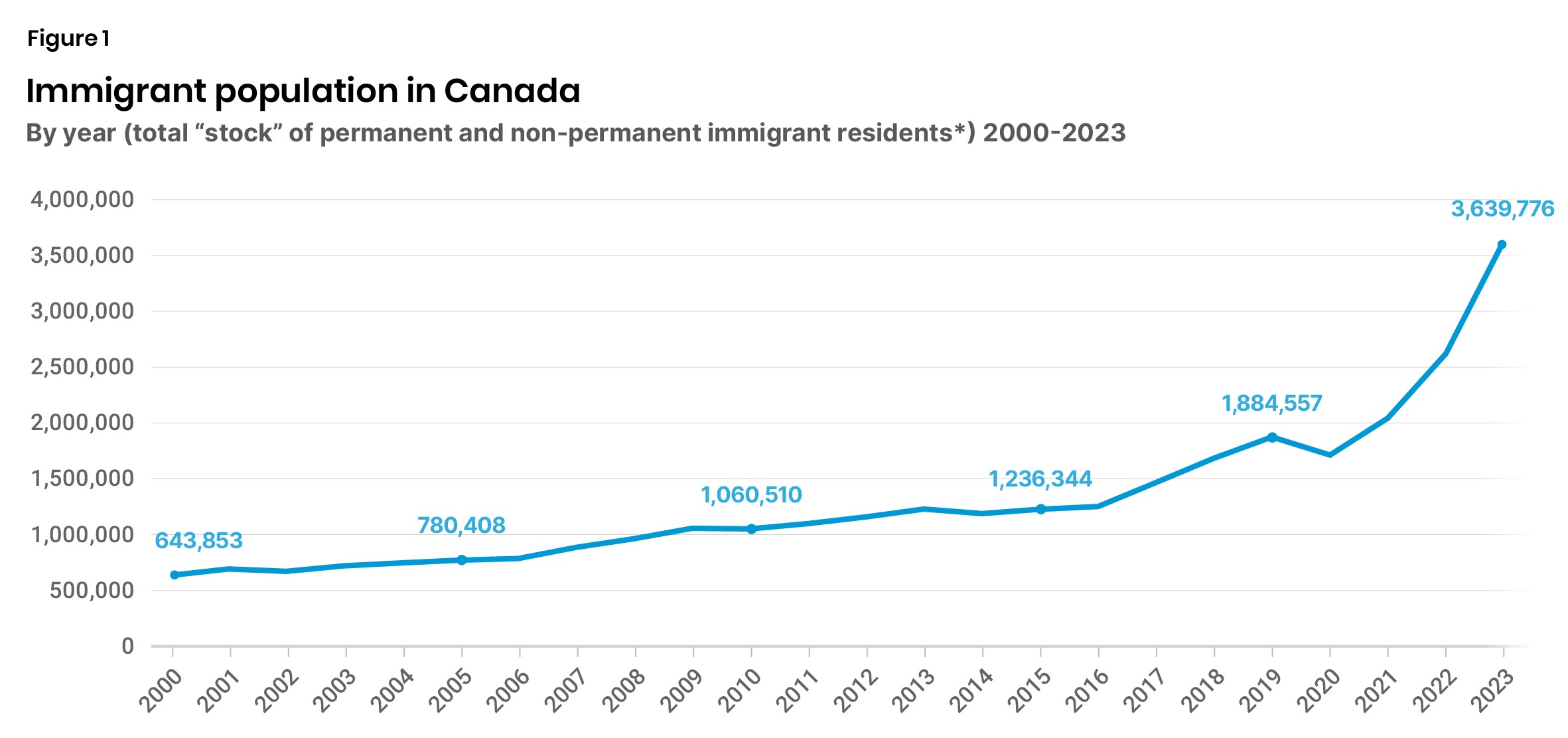

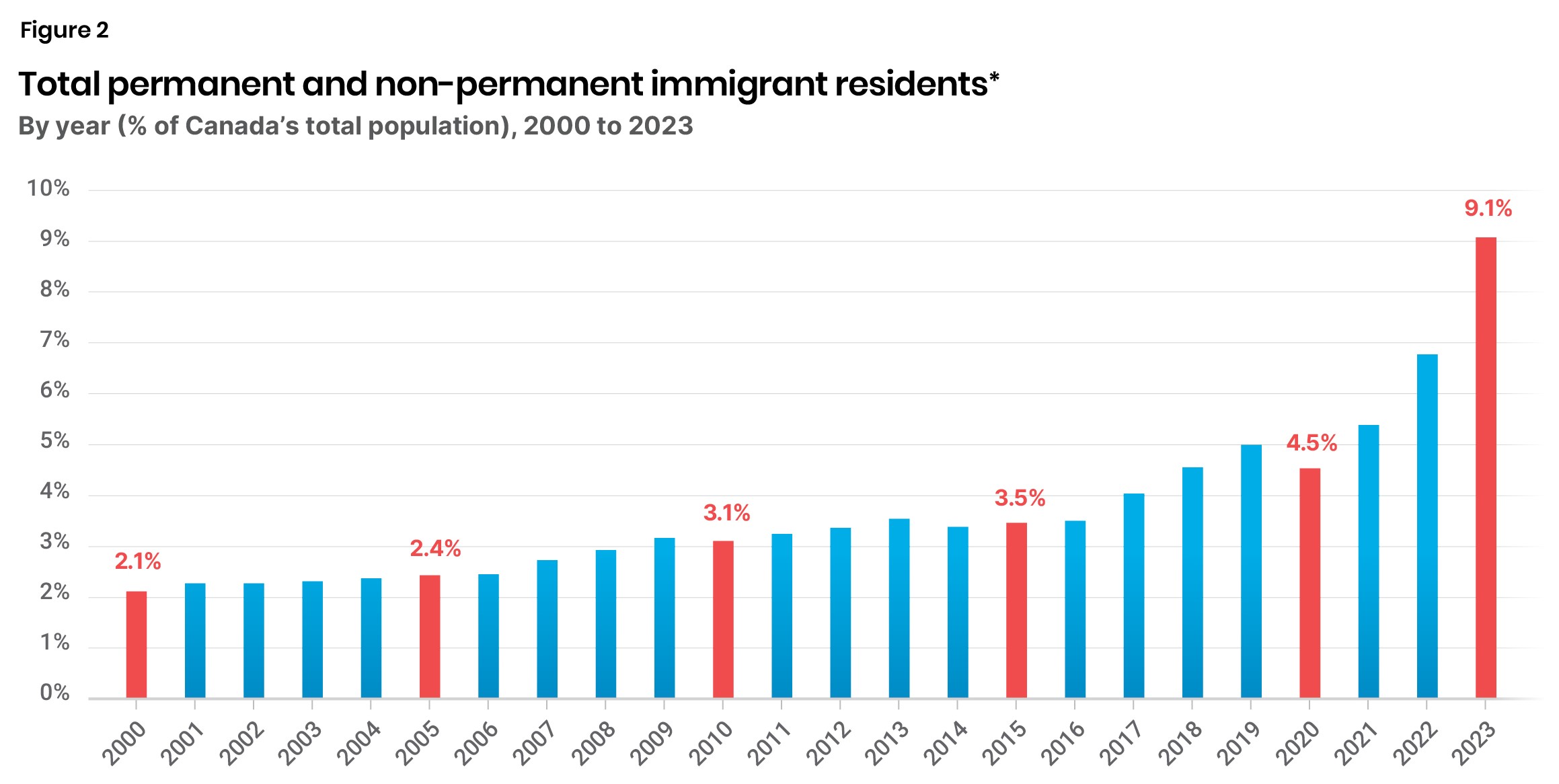

[a] To be clear, 3.6 million is not the number of immigrants arriving in Canada each year but the total “stock” (population at a given time) of immigrants who resided in Canada that year. Those 3.6 million people represent the accumulated, multi-year “intake” of the different categories: landed immigrants or permanent residents, temporary foreign workers, international student study permits, international mobility programs, and refugees and asylum seekers. The above-mentioned people are not Canadian citizens and may hold foreign citizenship.

[b] Note that the 9.1 percent figure is distinct from the total foreign-born population in Canada, which was 23 percent as of 2021. The difference between the two figures is that the latter percentage includes those foreign-born persons who have become Canadian citizens. The lower figure of 9.1 percent does not include Canadian citizens.

Since the evolutionary arrival of Homo sapiens between 550,000 and 700,000 years ago,1 migration has been the norm. Human migration is a fact of human existence.

Immigration can have both negative and positive outcomes. Negative outcomes can include the incapacity of a jurisdiction to handle sudden refugee flows in a time of war or in a natural crisis. Positive outcomes can include the alleviation of labour shortages, immigrant-based investment, the renewing of a nation’s population “stock” when it is in decline, among other benefits.

In some cases, whether immigration is negative or positive can depend on another reality: the introduction of new ideas, customs, and mores into an established population, and whether such changes are viewed as net negatives or net positives.

Migration is a fact, as is the impact of ideas and cultural transference—for ill or good. Such realities matter. They should be analyzed in the context of what constitutes the “good life” for a nation and all its citizens, be they “old stock” or newer arrivals. However, this paper focuses on one aspect of the good life: housing. It will compare recent immigration trends and their impact on housing with another important metric: housing completions and the type of housing units built. The data show that the demand for housing, in part spurred by historically high immigration levels, has not and cannot be matched by a concomitant increase in supply. Simply put, Canada’s housing industry cannot build shelters quickly enough to accommodate the still-unusually high level of immigration.

Housing has become a policy and political issue due to both its relative scarcity and its relatively high cost. A few examples:

The statistics support the bank’s observation. Rents across the provinces soared between 2018 and 2023, ranging from an 18.5 percent increase in Saskatchewan to 39.5 percent in Nova Scotia in those years. Other provinces fell within that range.5

Much analysis has been done on the supply side of Canada’s housing market, including by one of the authors of this paper.6 Many factors influence the price of housing. They include interest rates, which have been historically low for much of the last two decades, leading to asset inflation—including speculation in land and housing—and arguably a bubble in house prices in Canada (as measured by the house-price-to-income ratio).7

In addition, low interest rates have had both positive and negative impacts on affordability: They make mortgage payments more affordable in the short-term but can also boost housing prices as buyers amortize higher prices over more years—30 years for example, rather than 25 years. Longer amortization periods can lead to higher demand for house purchases than otherwise would be the case.

However, Canada’s scarcity of housing, including affordable rents and affordable sale prices for shelter, can also be partly explained by looking at the demand side—more specifically, population increases driven by immigration. As the Bank of Canada found in late 2023, while immigration to Canada is often positive in a number of areas, including the addition of skills and wealth, and for addressing labour shortages and other matters, “The rise in immigration is nonetheless contributing to pressures in inflation components linked to house prices, given that it is adding more to housing demand than to housing supply in the context of structural imbalances in the Canadian housing market.”8

With that reality in view, this study reviews the statistics on immigration to provide context on possible policy choices. If Canadians want the cost of housing to moderate or decline, the demand for housing should be addressed, even more than it has been in recent federal and provincial announcements.

A caveat: The role of immigration in the demand for housing has begun to be addressed by both provincial and federal governments in Canada. Each has taken some steps to address the country’s housing supply crisis, both policy-wise and rhetorically. At the federal level, the government has introduced some measures, including the Housing Accelerator Fund, that aim to provide municipalities with the funding they need to speed up the development of new housing units. In addition, governments have implemented a number of initiatives to settle people outside the major urban centers. Further, the 2024 federal budget includes increased spending on government-owned housing and subsidized housing along with a number of announcements and initiatives to tackle homelessness.

Provincially, several governments are implementing policies to streamline development processes, reduce zoning restrictions, and promote density in urban areas. Ontario, for example, has introduced the More Homes Built Faster Act, which aims to encourage the construction of 1.5 million homes over the next decade by easing zoning laws and facilitating land development. British Columbia has also focused on creating more affordable rental units and increasing housing construction in urban centres. These combined efforts aim to alleviate the housing shortage and make homeownership more attainable for Canadians.

Despite these efforts, housing supply in Canada may remain insufficient for several reasons:

This is because of the “substitution” effect. A government may announce that it will spend more on housing, including government-owned housing or subsidized housing. But there are only so many labourers, carpenters, bricklayers, plumbers, electricians, and others involved in home building to go around. If government spending on housing draws from the same pool of available construction labour, as it inevitably does, that spending (or more announcements) will not add to the total number of housing starts or completions; it will simply shift the payment for the new housing from private consumers to a government department—and eventually to taxpayers.

Thus, while announced reforms may be positive—whether or not they are depends on the reforms in question—they may not address underlying issues such as regulatory delays, limited land availability, and the substitution effect. These factors make it difficult to achieve the necessary scale of increases in the housing supply.

The numbers bear this out—the policy announcements and rhetoric have not yet affected raw immigration numbers enough to have a significant impact on housing availability. For example, by mid-2024, even though the federal government had earlier announced a cap on study permits for international students, the midsummer data showed that for the first five months of 2024 such permits were being approved at higher levels than the same five-month period in 2023.9 Similarly, the October 2024 announcement by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau that immigration intake levels were to be reduced to 395,000 in 2025 (from a planned 500,000) is relatively insignificant when considering the total flow of people into Canada from all categories, not just the main immigration categories.10

The impact on rentals, for example, from that policy change has been modest. There has been only a slight dip in rental asking costs, as of December 2024. In January 2025, average one-bedroom rental rates in Vancouver and Toronto were $2,530 and $2,360, respectively, while the rates for two-bedroom units were $3,430 and $3,077 in those two cities.11 The year-over-year rental price decline in those examples was between 6.3 percent (for a two-bedroom apartment in Vancouver) and 7.2 percent (for a two-bedroom apartment in Toronto). The average rental rate decline nationally has been just 2.1 percent for a one-bedroom unit and 2.3 percent for a two-bedroom apartment. To compare, the average cross-country rental rate in December 2024 across all categories was $2,109, which was still over $300 higher than the average rate of $1,805 recorded in December 2019.

The total number of immigrants in Canada from all categories has soared in recent years, as the detailed statistics show. Generally, there are five broad categories of immigrants who arrive in Canada, hold foreign citizenship, and only have permanent and temporary residency rights. They are:

The increase in the total stock of immigrants in Canada in all categories has been dramatic. Immigrants accounted for 643,853 people in 2000, or 2.1 percent of Canada’s population that year. That number rose to over 3.6 million people in 2023,[c] or 9.1 percent of Canada’s population that same year, due to the annual higher intake in those five categories (Figures 1 and 2).[d]

Note: *This includes permanent and non-permanent residents, refugees, asylum-seekers, international students, temporary foreign workers, and international mobility program. They are not Canadian citizens and may hold foreign citizenship.

Source: Authors’ calculation based on Statistics Canada, IRCC, and UNHCR data (2024).12

Note: *This includes permanent and non-permanent residents, refugees, asylum-seekers, international students, temporary foreign workers, and international mobility program. They are not Canadian citizens and may hold foreign citizenship.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Statistics Canada, IRCC, and UNHCR data (2024).

The social impact of an increased number of permanent and non-permanent immigrants is difficult to quantify. While some economic sectors benefit (including businesses and consumers) from lower labour costs—and colleges and universities reap more and usually higher tuition dollars—other sectors feel the strain. Those sectors include housing, where there are shortages, and schools and hospitals, where there is overcrowding. The latter two are issues for further analysis and study; this report focuses solely on the housing shortage.

[c] To be clear, 3.6 million is not the number of immigrants arriving in Canada each year but the total “stock” (population at a given time) of immigrants who resided in Canada that year. Those 3.6 million people represent the accumulated, multi-year “intake” of the different categories: landed immigrants or permanent residents, temporary foreign workers, international student study permits, international mobility programs, and refugees and asylum seekers. The above-mentioned people are not Canadian citizens and may hold foreign citizenship.

[d] The growth rate in Canada’s population was twice that of other G7 countries from 2016 to 2021 (See Statistics Canada (2022), “Canada Tops G7 Growth Despite COVID,” The Daily (February 9), Statistics Canada <https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220209/dq220209a-eng.htm>.

The significant increase in immigration in recent years has not been matched by an equally significant increase in housing completions. (See the Appendix for details on each immigration category.)

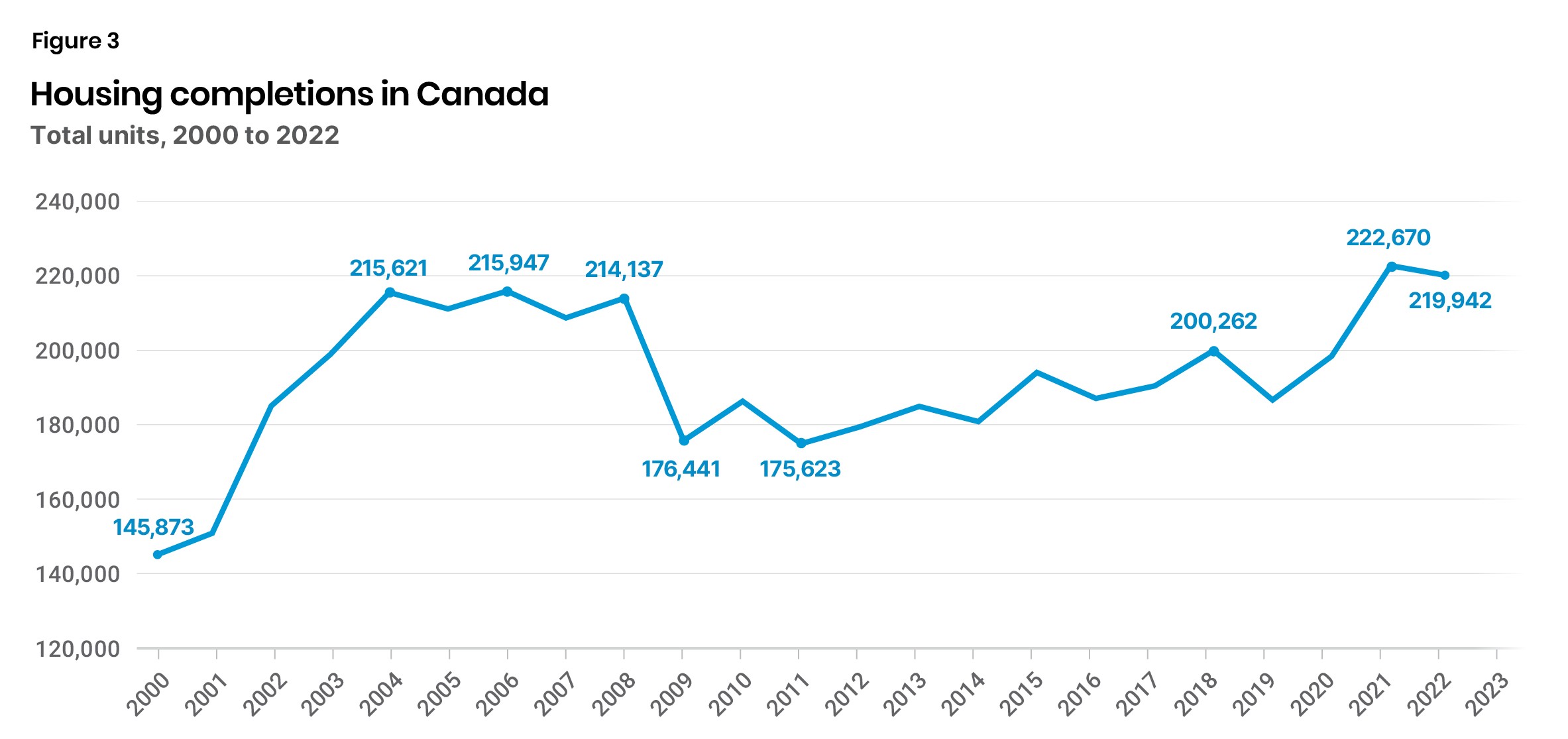

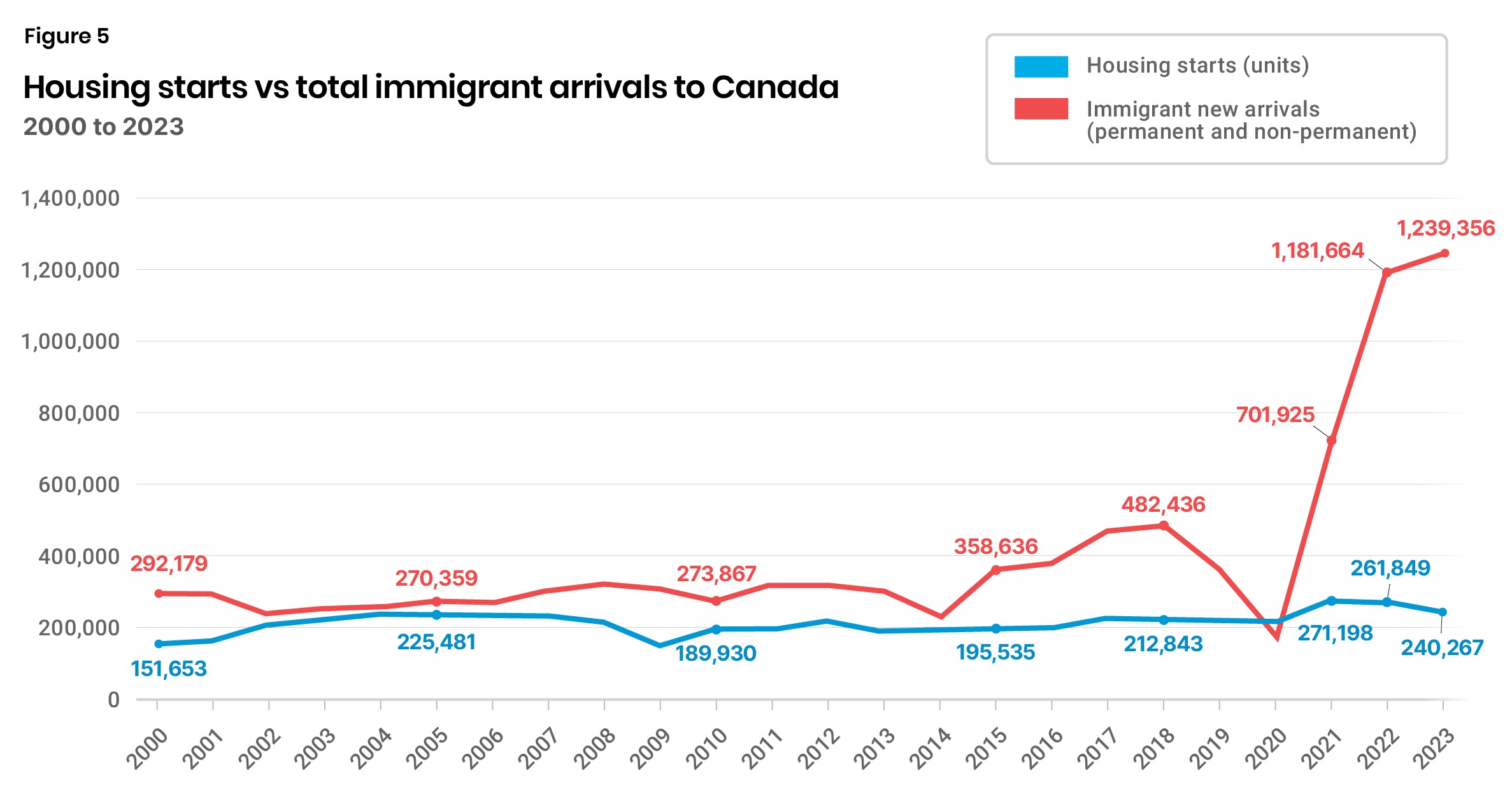

To understand why increasing the housing supply cannot alone solve the problem of the excess demand that has been partly caused by high immigration levels, consider Figures 3, 4, and 5. They show housing completions in Canada between 2000 and 2022, and housing starts in the most recent three years compared with immigrant arrivals, by year, from 2000 to 2023.13

In 2021, 222,670 homes of every variety were completed in Canada, the highest number in the period examined (Figure 3). However, that high watermark is unlikely to be repeated. The annual average over the 2000 to 2022 period was 192,880 housing completions.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 34-10-0135-01.14

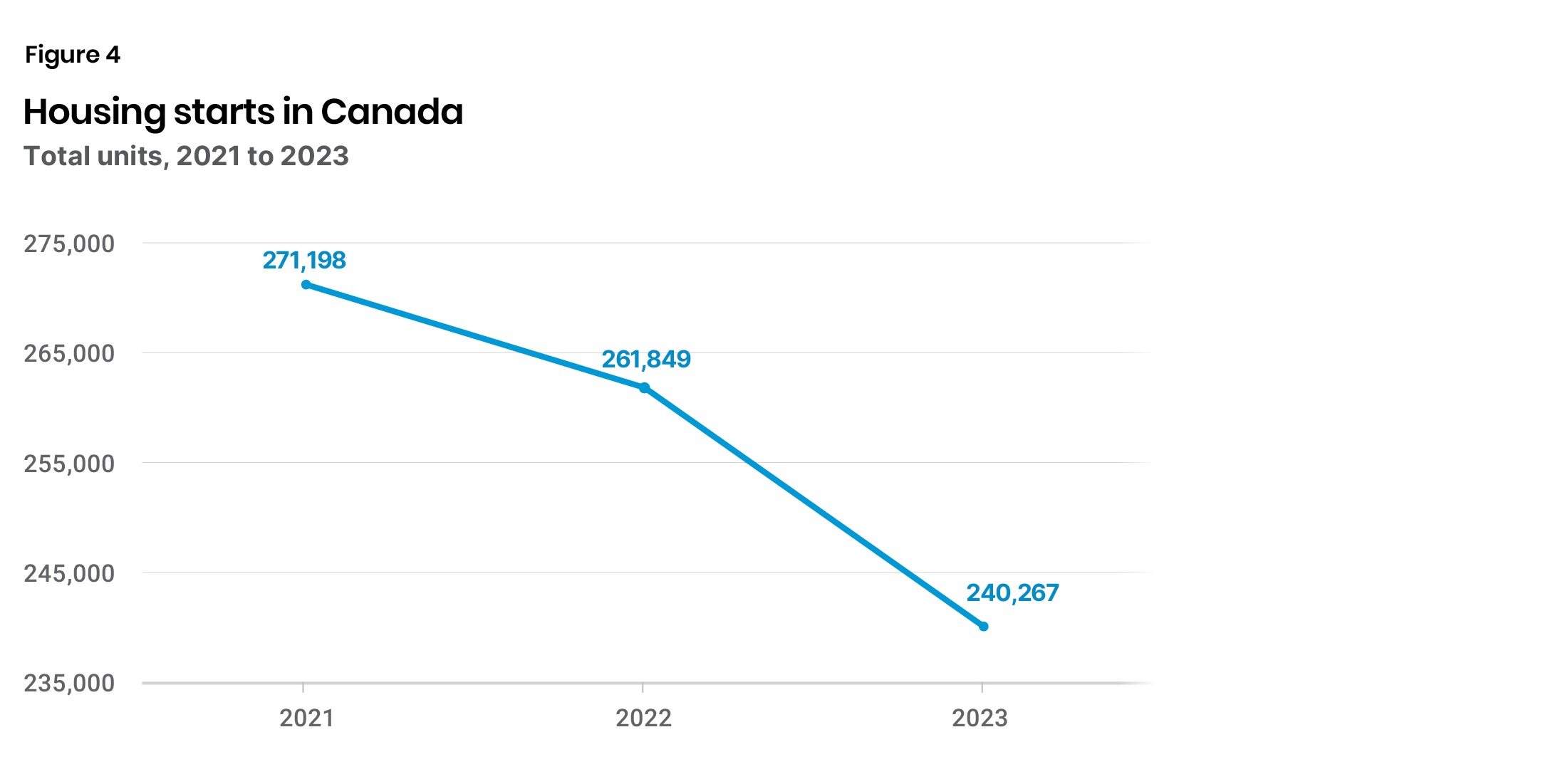

The higher number of housing completions is unlikely to be repeated as housing starts are declining. From 271,198 housing starts in 2021, the numbers have dropped: there were just 240,627 housing units started in 2023 (Figure 4). Higher completions and higher supply cannot take place when housing starts are down.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 34-10-0135-01.15

In the most recent three-year period for which full data are available, over 3.1 million immigrants arrived in Canada while just over 773,000 housing units were built. To be clear, Canada does not require an exact match between the number of housing units built and the number of immigrants arriving; as is the case with existing Canadians, only a portion of immigrants live alone and require a single-person apartment, townhouse, or home. However, as Figure 5 shows, the larger trend is that housing starts have remained at near constant levels since the year 2000, even as immigration has soared, especially in recent years. That is the demand side of the housing demand-and-supply equation that has mostly been overlooked.

Notes:

- International migration data is for the period from July 1 to June 30.

- A non-permanent resident refers to a person from another country with a usual place of residence in Canada, and who has a work or study permit or who has claimed refugee status (asylum claimant, protected person, or member of related groups).

- Data for non-permanent residents are net. Net non-permanent residents represent the difference between the inflows and outflows of non-permanent residents to Canada.

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 34-10-0135-01 and 17-10-0014-01.

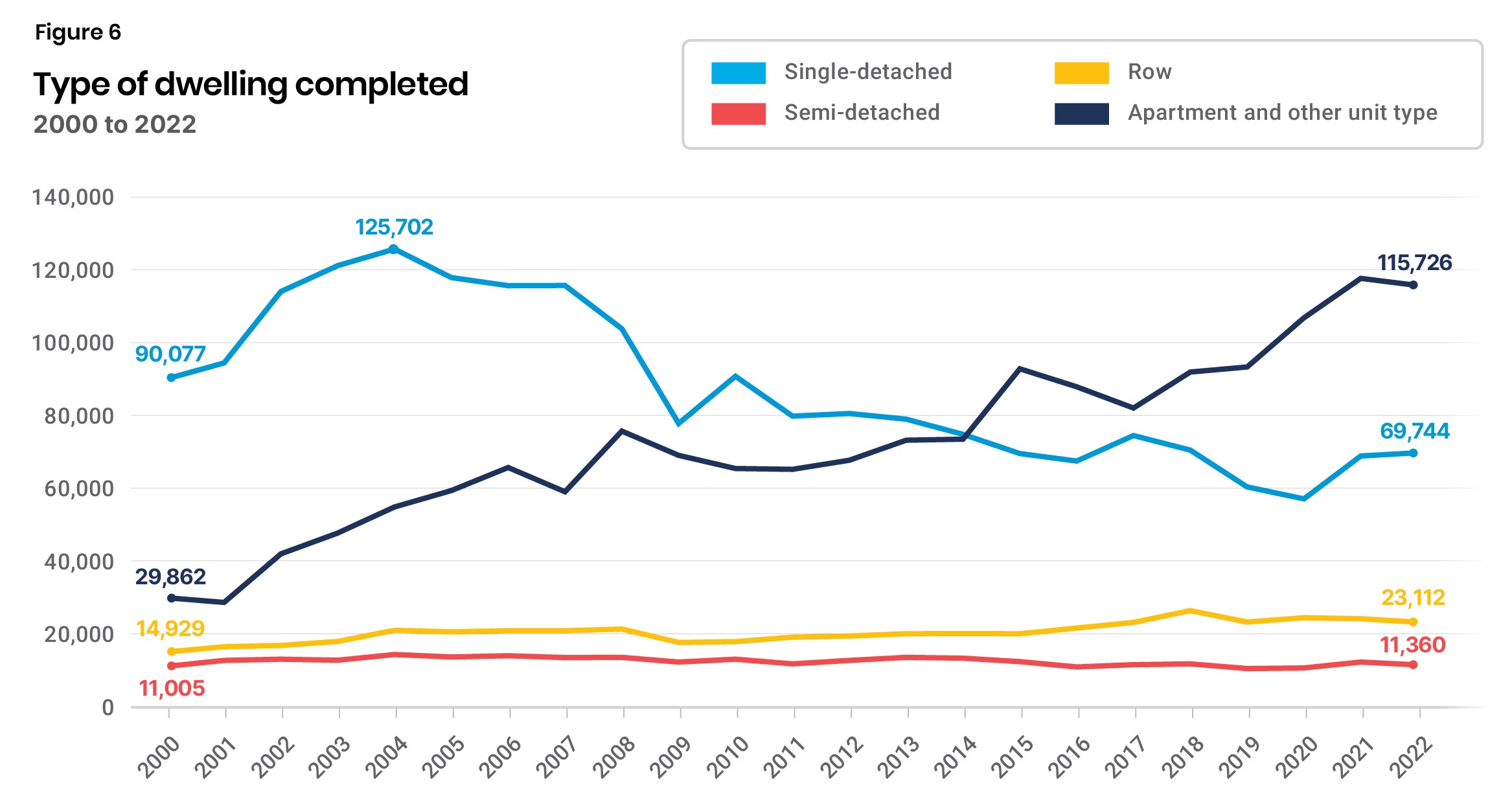

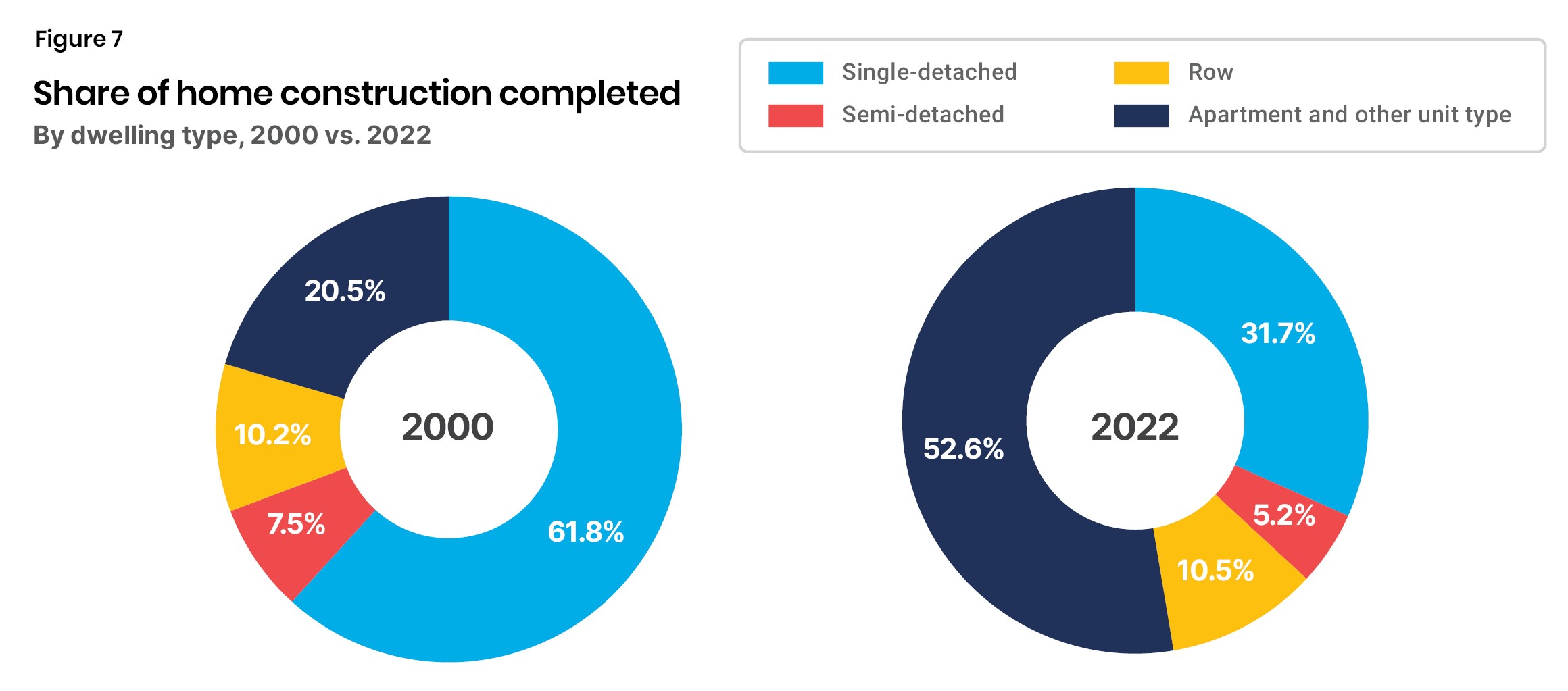

The other element in supply that matters is the type of housing completed. The type of housing built over the previous two-plus decades has shifted (Figure 6). In 2000, for example, single-detached housing completions represented 90,077 of 145,872 housing units completed, or 61.8 percent of all housing completions. By contrast, in 2022, single-detached housing completions accounted for just 69,744 units of 219,942 total housing units built, or 31.7 percent of all housing completions that year. By comparison, completions of “apartments and other unit types” (i.e. excluding semi-detached and row homes) rose from 29,862 in 2000 (20.5 percent of all housing stock completed that year) to 115,726 completions in 2022 (52.6 percent of all housing units built that year) (Figure 7).

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 34-10-0135-01.

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 34-10-0135-01.

One could assert that the large-scale shift to more apartment-style housing may help place more people in housing and/or is a response to affordability issues, some of which precede the trends of rapidly rising immigration. However, the shift affects the demand-supply balance because, on average, single family homes contain more bedrooms than do semi-detached homes, row houses, or apartments.

In other words, not only are housing completions not keeping up with much higher immigration flows in recent years, the type of housing units completed recently have fewer bedrooms on average than the housing stock completed two decades ago. Fewer bedrooms built means fewer possibilities for shelter at the very time immigration intake has increased dramatically. To help alleviate the housing shortage, Canadians need more housing built with more bedrooms to accommodate more people, but completion data show that the opposite is happening.

Human migration is a fact of human existence and can bring with it negatives and positives—most often mixtures of both. Our view is that immigration to Canada has mostly been a net positive over the decades—we view immigration broadly as a “good thing”—though caveats beyond housing belong in a separate analysis.

As it applies to housing—and looked at from the demand side and its negative consequences from upward pressure on both rental costs and housing prices—current high immigration rates, even after recently-announced reductions, now constitute too much of a good thing.

High immigration intake in selected categories should be further reduced beyond the announcements made in recent months. We will offer only general guidance but note that obvious categories for further reductions include students and those nearing or at retirement, including those arriving as part of family reunification. Instead, workforce needs should be of paramount importance, including the necessary labour needed to build more housing. In addition, unreasonable regulatory delays from all levels of government associated with new builds should end, as one of the authors has noted in another report.16

Such reform is necessary as new housing supply has not, and cannot, be built rapidly enough to accommodate all arrivals to Canada—or even Canadians already here. The data trends on housing starts and completions in recent years show there is no reason to expect that that situation will change in the foreseeable future. To moderate demand in the housing market and reduce the upward pressure on rental costs, immigration in most categories should be reduced significantly.

Please see PDF for appendices.

Mark Milke, Ph.D., is the founder and president of the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. Mark is a public policy analyst and author with six books, over 70 studies, and over 1,000 columns published in the last 25 years. His policy work has been published by numerous think tanks in Canada and internationally. He is editor of the Aristotle Foundation’s first book, The 1867 Project: Why Canada Should Be Cherished–Not Cancelled.

Ven Venkatachalam, Ph.D., is a senior economist at the Aristotle Foundation. He empirically anchors its work in data and statistics. He is an economic and social science policy researcher with expertise in multiple areas including economic and fiscal policy, immigration, international relations, trade, energy, governance, education, tourism, and NGO matters. He has consulted for governments, NGOs, and private sector organizations across Asia, Europe, Canada, and the United States.

About the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy

Who we are

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new education and public policy think tank that aims to renew a civil, common-sense approach to public discourse and public policy in Canada.

Our vision

A Canada where the sacrifices and successes of past generations are cherished and built upon; where citizens value each other for their character and merit; and where open inquiry and free expression are prized as the best path to a flourishing future for all.

Our mission

We champion reason, democracy, and civilization so that all can participate in a free, flourishing Canada.

Our theory of change: Canada’s idea culture is critical

Ideas—what people believe—come first in any change for ill or good. We will challenge ideas and policies where they are in error, and buttress ideas anchored in reality and excellence.

Donations

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity and all donations will receive a tax receipt. To maintain our independence, we do not seek nor will we accept government funding. Donations can be made at www.aristotlefoundation.org.

Research policy and independence

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy has internal policies to ensure research is empirical, scholarly, ethical, rigorous, honest, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge and the creation, application, and refinement of knowledge about public policy. Our staff, research fellows, and scholars develop their research in collaboration with the Aristotle Foundation’s staff and research director. Fact sheets, studies, and indices are all peer-reviewed. Subject to critical peer review, authors are responsible for their work and conclusions. The conclusions and views of scholars do not necessarily reflect those of the Board of Directors, donors, or staff.

The logo and text are signs that each alone and in combination are being used as unregistered trademarks owned by the Aristotle Foundation. All rights reserved.

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a registered Canadian charity. Our charitable number is: 78832 1107 RR0001.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER