Mark Milke, Western Standard, June 26, 2023

“Your rights take priority over those of the state… The collectivity is not the bearer of rights: it receives the rights it exercises from the citizens.”

— Pierre Trudeau, Cité Libre dinner speech, Montreal, October 1992

It is time to debunk a nonsensical myth that has metastasized in Canada in recent years: That any attempt to rank ideas and values as preferable or civilized is intolerant at best, racist at worst, and a sign of a misplaced cultural superiority complex.

For example, in a 2015 year-end interview with the New York Times, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau described his view of Canada this way: “There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada. There are shared values— openness, respect, compassion, willingness to work hard, to be there for each other, to search for equality and justice.”

The prime minister then contradicted his own claim that Canada has no “mainstream” or “core identity” by going on in the same interview to trumpet the “shared values” of Canadians. He listed what he thought those were, another way of saying that Canadians do have a core identity and that there is a dominant, i.e., mainstream view.

But beyond the prime minister’s contradictory conceptual confusion, there was a practical reason to articulate a standard of beliefs and behaviour: any country that wishes to survive as a functioning entity and avoid cracking up into a broken, dysfunctional set of competing tribal clans needs agreement on the basics of what citizens should rally around.

Also, Trudeau made an historical error: Canada does have an identity and one would think that Trudeau, himself the biological product of French and English coupling, would have been aware of it. Canada, as with other nations, is a fusion of battles and ideas and political compromises mostly, though not exclusively, between the English and the French (the armies of both colonial powers had indigenous allies).

In general historical terms, one can reference the pre-1759 history of French Canada or the decisive victory of the English over the French on the Plains of Abraham in that year and the Royal Proclamation of 1763; the inflow of United Empire Loyalists during and after the American Revolution; the 1840 Act of Union that fused together the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada; 1867 and Confederation; or even the 1982 Constitution courtesy of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and willing premiers of the day who recognized the English and French dominance of British North America and enshrined both languages into the Constitution.

As well, ponder the ideas that bound Canada together, British liberalism and French ideology They assume the worth of the individual and were directly inherited from the United Kingdom, but are also the product of Jewish and Christian intellectual history, as well as the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Enlightenment.

These ideas and developments include the:

• Magna Carta of 1215 and its enunciation of rights including to property and on the limits on rulers and the implicit assumption of the rule of law;

• Enlightenment writings of John Locke on the social contract and his overall contribution to liberal thought;

• 1688 Glorious Revolution which limited the power of the monarchy; the economic works of Adam Smith and others on the usefulness of free markets;

• value of political and societal evolution rather than revolution written about by Edmund Burke;

• public and parliamentary anti-slavery advocacy of abolitionists, most chiefly the initial efforts of British parliamentarian William Wilberforce that led to millions more converted to that cause

• John Stuart Mill on the “why” of liberty;

• and Mary Wollstonecraft on the rights of women—among many others.

Positively, it is precisely because such concepts are ideas and not connected to ethnicity, race, or gender, that they can and are adopted by peoples the world over—anyone can adopt preferences for a free nation, a free economy, and equal opportunity. The most recent example has been Hong Kong residents who, while they obviously share the culture, history, and ethnicity of those in mainland China, have been in near-constant protest against the regime in Beijing for withdrawing freedoms first tasted under British colonial rule. Also, many among the older generations in Hong Kong deliberately fled communist China earlier for just such freedoms.

All this matters to a proper understanding of Canada including the rights and responsibilities assumed “normal” today. All of the foregoing and more were critical to those who shaped a liberal democratic country on the northern half of the North American continent pre- and post- Confederation.

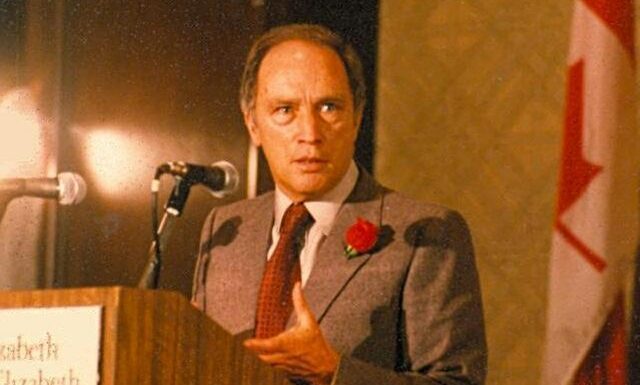

In contrast to Justin Trudeau, his father, Pierre Trudeau, prime minister of Canada between 1968 and 1979 and again from 1980 to 1984, was clear about Canada’s core identity and its historic commitment to classical notions of individual liberty.

Unlike many of today’s politicians, this equal treatment of the individual in law and policy is something that Pierre Trudeau grasped and argued for in 1992 in debates over the Charlottetown Accord. That referendum which, if passed as an amendment to the Constitution, would have granted special status to Quebec. It would have allowed its government to treat citizens differently based on their identity and language preference (anglophones, francophones, or others).

That accord would have constitutionalized the allowance of such discriminatory treatment. It was why Trudeau was clear that to recognize Quebec as a distinct society and constitutionalize its “collective” right to discriminate against individuals was wrongheaded and illiberal.

As Trudeau remarked: “That is why the French Revolution established liberty as a fundamental right. No one is subject in his fundamental rights to the state: that is liberalism —which says that the individual in the exercise of his fundamental rights precedes the state, and all individuals are equal.”

Unlike his son, Pierre Trudeau grasped that tribalism based in unchangeable characteristics has been the norm in human history, which is why citizens must instead consciously think of each other as individuals first and define each other that way in law and policy if they are to avoid the unresolvable conflicts that arise between collectives.

This attention to individual rights is why Pierre Trudeau saw the individual and the equal treatment of individuals as paramount: “Citizens, you are all first of all equal among yourselves…,” said Trudeau in the same speech.

This attention to individual rights is also necessary because a collective writ large, such as governments, possess substantial powers and can make life exceedingly difficult for an individual citizen. Such a collective can even become tyrannical. This why in the same rhetorical breath when he emphasized the need for equality among citizens, Trudeau also emphasized that rights ultimately flow from citizens and not the state “[Y]our rights take priority over those of the state… The collectivity is not the bearer of rights: it receives the rights it exercises from the citizens.”

This, then, is why equal treatment under the law is such a critical policy: Individuals “hand” power to the state and in turn the state must not treat one individual as inherently more privileged or more punishable based on one’s identity.

To do otherwise is to break the bargain between the state and the individual: I allow the state to engage in certain actions with power transferred from me as a citizen, and in activities that only a government can do — set up courts, arrest those who break laws, tax me for some good that presumably only a collective can provide — and in turn, the state promises not to prefer another citizen over me but to treat us as moral and legal equals.

Mark Milke is president of the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. This chapter excerpt is from the Aristotle Foundation’s new book, The 1867 Project: Why Canada Should be Cherished—Not Cancelled, with 20 authors and edited by Mark Milke.

Like our work? Think more Canadians should see the facts? Please consider making a donation to the Aristotle Foundation.

The logo and text are signs that each alone and in combination are being used as unregistered trademarks owned by the Aristotle Foundation. All rights reserved.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

are signs that are each alone and in combination are being used as unregistered trademarks owned by the Aristotle Foundation. All rights reserved.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER