Since 1876, the Indian Act has contained a tax exemption for real and personal property owned by Indians,a either individually or collectively, on Indian reserves. The purpose of the exemption was to protect the reserves, which were federal Crown property set aside for the use and benefit of First Nation people, from being taken over by local or provincial governments for non-payment of taxes.

The exemption is consistent with the general principle of Canadian law that one government cannot tax another government, and it has effectively served its purpose of protecting reserve land from confiscation by local governments. It is also arguably consistent with the principle of equality before the law, which says that people should be divided into legal categories only when there is a demonstrable difference between groups that is relevant to public policy.

The Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in the Nowegijick case (1983) extended the exemption to include income earned, or purchases made, by Indians on reserve. This special privilege applying to the approximately one million Registered Indians in Canada has no logical foundation and serves no obvious purpose of public policy. Its main outcome has been to generate resentment by the other 39 million Canadians who are required to pay taxes on income and sales.

Not being part of the Constitution, the tax exemption for Registered Indians on income and sales could and should be rescinded by federal legislation. The revenue gained by taxing Registered Indians’ income and sales could be returned to the First Nations to help them support their own governments, making self-government less of a slogan and more of a reality.

Since the 1980s, some progress has been made in this direction. Changes in legislation have allowed about 160 First Nations to create their own property taxes. These, however, are levied mainly on leases of reserve land to outsiders, such as those underpinning railways, pipelines, commercial parks, and residential developments. The next logical step would be to extend such taxes to reserve property held by Indians in the form of Certificates of Possession.

Federal legislation has also created two different ways in which reserve governments can charge sales taxes for on-reserve transactions. Used by a few First Nations, these do have an impact on their own members, though most of the revenue they generate comes from non-members shopping on reserve. Finally, there is a form of income tax used by First Nations who have signed modern-day treaties under which their lands are not reserve lands in the sense of the Indian Act and hence do not carry a tax exemption. This income tax applies mainly to First Nation people who are employed by the band

government and who are ultimately paid by the federal government. In practice, it ensures that federal transfers supporting the community stay within the community.

These small-scale forms of property, income, and sales taxation are all praiseworthy initiatives created by cooperation between First Nations and the federal government. They belie the common belief that the Indian Act must be totally repealed because it cannot be amended. In fact, Indigenous policy, like all other policy areas in Canada, is susceptible to gradual improvement through consultation, negotiation, and legislative amendment.

These time-honoured democratic processes have also been used on a small scale, and can be extended further, to modernize the taxation of Registered Indians. In a constitutional democracy like Canada, there is little justification for exempting one subset of Indigenous people from taxation. Sharing in the expense of government is a mark of true citizenship and self-government that should gradually be extended to all Canadians.

Equality before the law is a bedrock principle of constitutional government and liberal democracy. Of course, citizens sometimes need to be divided into categories for purposes of public policy. The needs of women differ in some ways from the needs of men, and children require special protection under the law, as do seniors who are no longer able to look after themselves. But such legal categorization should always be linked to demonstrable differences in need between classes; otherwise, it is merely a way

for some groups to use the state to profit at the expense of others.

This paper examines one case of special fiscal treatment in Canada: the exemption from taxation of property on Indian reserves or of income earned by Registered Indians on reserves. This a unique situation in Canadian law. No other race, ethnic group, religion, or cultural community enjoys such a privilege.b 1 It is contrary to the general ethos of democratic societies, which assumes that the state should treat all citizens equally and that all citizens should pay their fair share to support the state. Not surprisingly, the tax exemption enjoyed by Registered Indians has often been controversial. In 50 years of speaking to Canadian audiences about Indigenous issues, I have found that the question of taxation generates more emotion than any other topic because it directly raises issues of fairness that are central to democratic politics.

The examination of special fiscal treatment for one subcategory of Indigenous Canadians must be placed in this context: The historic and existing government spending on Indigenous Canadians, contrary to perceptions or claims by some, has been substantial and often in addition to what was and is required by treaties or the Constitution. For example, a pathbreaking piece of research published by the Fraser Institute found that federal spending on Indian programming rose from $79 million in 1946-47 to almost $7.9 billion in 2011-12. Even after allowing for inflation, the growth of the welfare state, and the rise in the Aboriginal population, this increase was more than twice as high as the increase in per capita federal spending on Canadians generally.2 And the dramatic rise has continued since then. Indigenous spending was projected at over $27 billion in Budget 2022,3 and over $29 billion in Budget 2023.4 Canada now spends more on Indigenous programming than on national defence.

This growth in spending was initially driven by the growth of the welfare state as the federal government tried to provide better education, medical care, and other social services to Indigenous people. More recently, however, compensatory payments for alleged past injustices are playing an increasing role. This trend started with a settlement of over $5 billion to residential school “survivors” negotiated in 2005.5 Numerous other lawsuits have been settled since Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government came to power in 2015, the largest being a $43.3 billion settlement for children taken from Indian reserves into foster care,6 and others are still under negotiation. What used to be the Department of Indian Affairs is well on its way to becoming a Department of Indigenous Reparations.

Given the significant expenditures on First Nations specifically and Indigenous Canadians more generally, this paper explores the current situation of Indigenous taxation in Canada as well as the historical development of the tax exemption, concluding with some recommendations for change. Since the minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations has recently stated that the Indian tax exemption is up for review,7 it is a propitious time to make some suggestions.

To summarize,

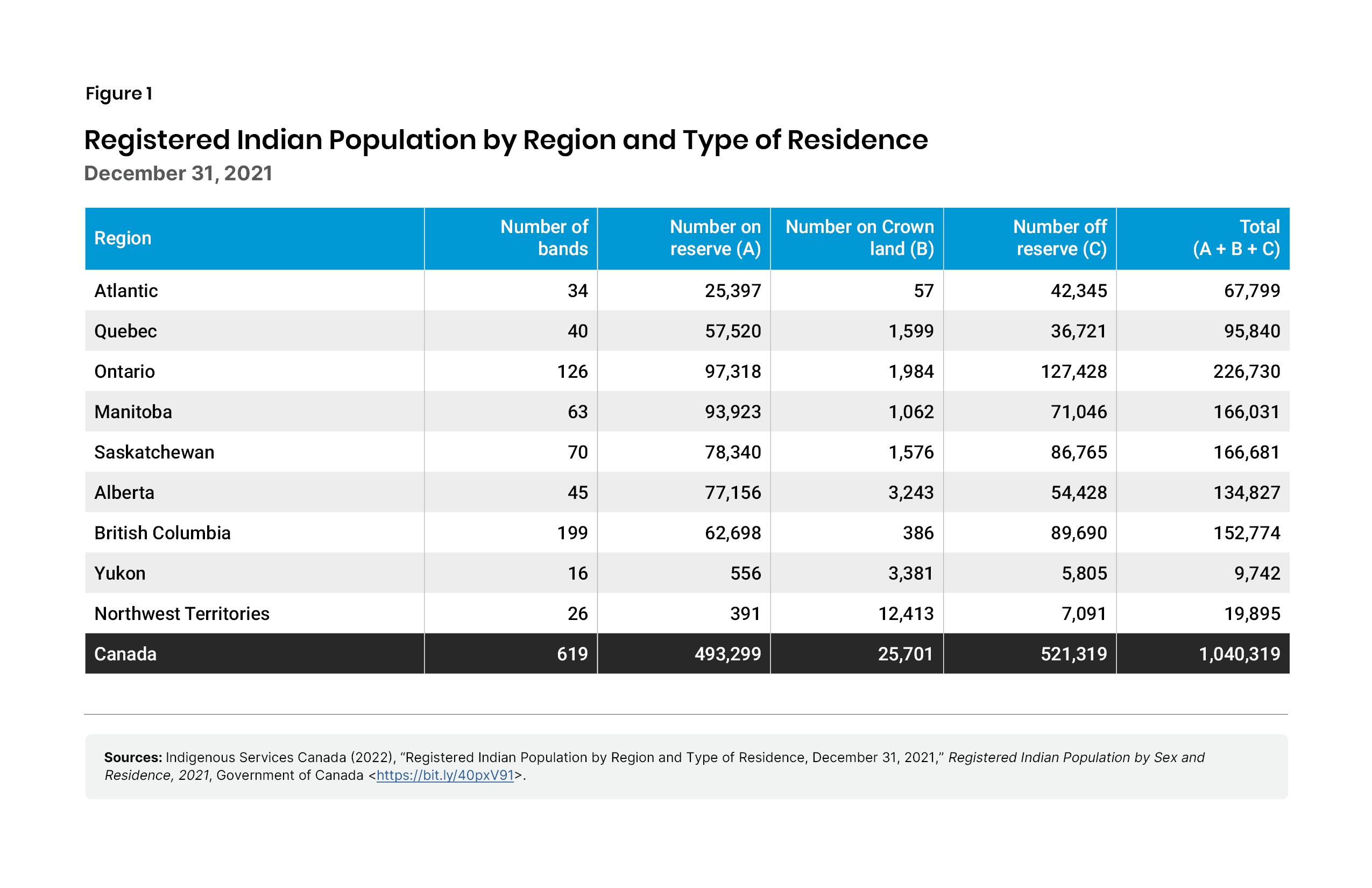

Through section 87 of the Indian Act, Indians in Canada are exempt from taxation on real and personal property located on Indian reserves. Judicial interpretation of the legislation has also made them exempt from taxes on many forms of income earned or received on reserve. These exemptions do not apply to Indigenous people in general, only to those whose names are entered on the Indian register: 1,040,319 at the end of 2021, about 2.8 percent of the population of Canada.8 Inuit, Métis, and non-status Indians are not listed on the Register and are not exempt from taxation. Figure 1 shows the distribution of Registered Indians across Canada.

The tax exemptions apply only to Registered Indians on reserve; they do not apply to corporations, even if owned by Indians. According to Figure 1, slightly less than half of Registered Indians are living on reserve at the present time. The number living off reserve has been increasing, not so much because people are leaving reserves but because many non-status Indians who have long lived off reserve have recently regained status due to legislative changes.9 Moreover, residence on reserve is not an exact proxy for exemption from taxation.

A reserve resident may work or own property off reserve and thus be subject to taxation, while a non-resident may work or own property on reserve and thus be protected. But in very round numbers, we might estimate that about 400,000 Registered Indians are exempt from taxation, about 1 percent of Canada’s total population.

Law professor Bradley Bryan has attempted to diminish the importance of the tax exemptions, arguing that “about 200,000 [Registered Indians] were of working age (between the ages of 14 and 65) [in 2016]. Of the working population, about 75,000 earned under $10,000 in annual income or less, meaning they would not have paid tax, regardless of their identity or place of residence.”10 However, the argument fails as a general proposition. It may be true of income tax, but the entire reserve population benefits from exemption from property and sales taxes, regardless of their employment status. Thus, the loss of revenue is probably greater than Bryan suggests.

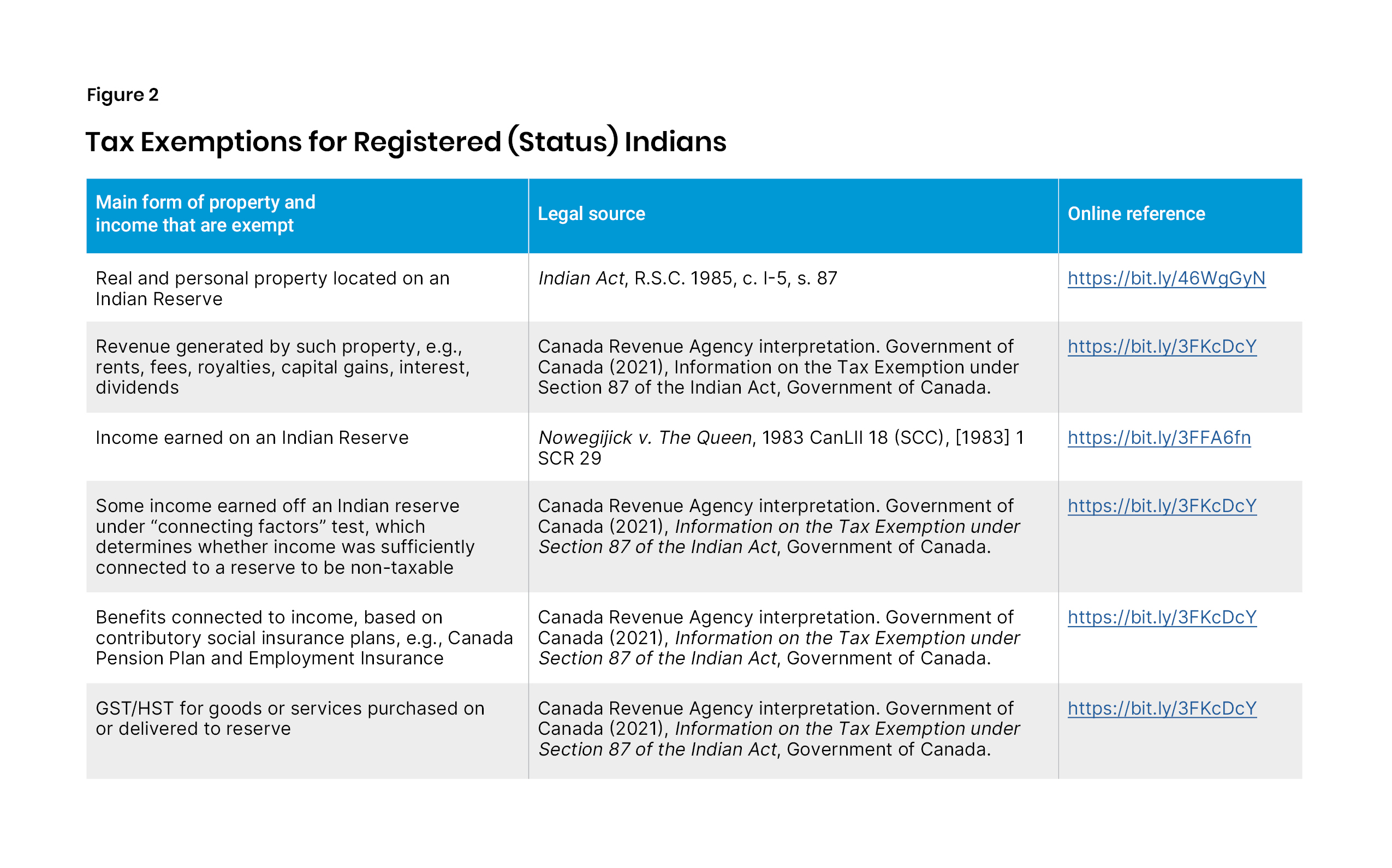

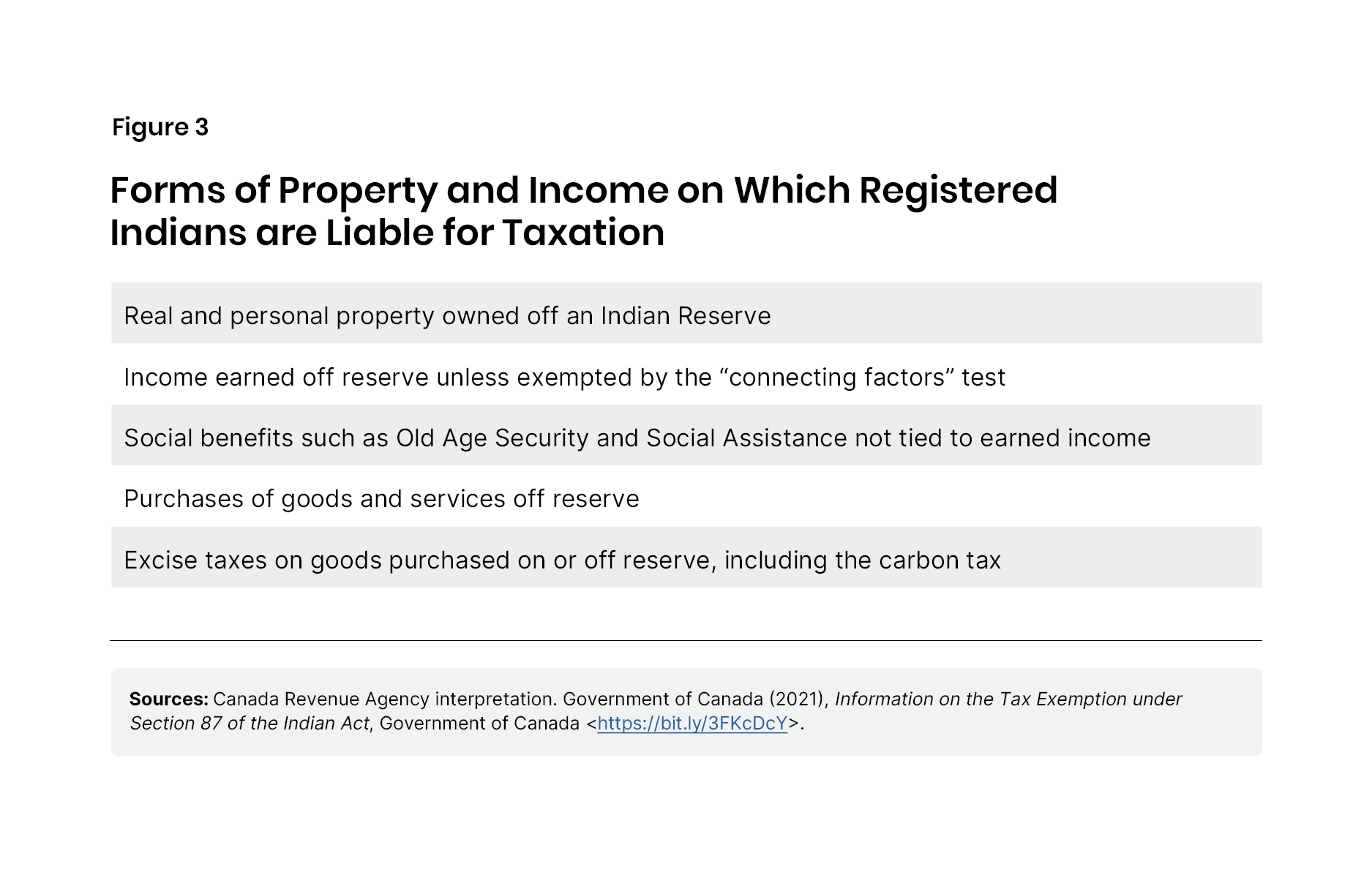

Figure 2 lists the main forms of property and income that, if owned or received by Registered Indians, are exempt from taxation. It briefly describes the exemption, identifies the legal source of that exemption, and provides an online reference to the source. Figure 3 shows the forms of property and income that are not exempt and on which status Indians pay the same taxes as other Canadians.

These exemptions can be quite valuable and thus create incentives to locate, or appear to locate, economic activities and holdings on reserve. Considerable gamesmanship is inevitable, though the number of people involved is small compared to the population of Canada.

The origin of the Indian tax exemptions is Section IV of An Act for the Protection of the Indians in Upper Canada from Imposition, and the Property Occupied or Enjoyed By Them from Trespass and Injury, passed in 1850 (I have added subsection numbers for ease of exposition):

And be it enacted, That (1) no taxes shall be levied or assessed upon any Indian or any person inter-married with any Indian for or in respect of any of the said Indian lands, (2) nor shall any taxes or assessments whatsoever be levied or imposed upon any Indian or any person inter-married with any Indian so long as he, she or they shall reside on Indian lands not ceded to the Crown, or which having been so ceded may have been again set apart by the Crown for the occupations of Indians.11

This statute was passed shortly after the Upper Canada legislature adopted the Municipal Corporations Act of 1849, which regularized the taxing authority of local governments. Taken in its historical context, the first clause of the new law was obviously designed to protect Indian lands from predation by local and provincial governments. The meaning of the second clause is less obvious. It seemed to prohibit any sort of tax upon Indians living on reserve; but at the time of passage, personal income taxes, corporate income taxes, and sales taxes did not exist in Canada, so it is hard to know if legislators had anything specific in mind.

The tax exemption was carried forward in sections 64 and 65 of the Indian Act of 1876, but was limited to real and personal property on reserve:

Consistent with the purpose of protecting the land and property of Indians, the statute now specified the immunity of real and personal property from taxation; it did not forbid all taxes of any type upon Indians. In specifying the immunity of real property from taxation, the Indian Act of 1876 implicitly ratified the on-reserve payment of excise taxes and customs duties, which as indirect taxes would be paid by the manufacturer or importer and then incorporated into the sale price of the merchandise.

The decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Mitchell v. Peguis Indian Band (1990) confirmed the importance of protecting reserve lands from local and provincial governments. Justice Gérard La Forest wrote:

The exemptions from taxation and distraint [seizure of property for debt] have historically protected the ability of Indians to benefit from this property in two ways. First, they guard against the possibility that one branch of government, through the imposition of taxes, could erode the full measure of the benefits given by that branch of government entrusted with the supervision of Indian affairs. Secondly, the

protection against attachment ensures that the enforcement of civil judgments by non natives will not be allowed to hinder Indians in the untrammelled enjoyment of such advantages as they had retained or might acquire pursuant to the fulfillment by the Crown of its treaty obligations. In effect, these sections shield Indians from the imposition of the civil liabilities that could lead, albeit through an indirect route, to the alienation of the Indian land base through the medium of foreclosure sales and the like….12

According to this line of interpretation, the purpose of s. 87 was to protect the lands and property of Indians, not to confer a general welfare benefit.

After a major rewrite of the Indian Act in 1951, the exemption now reads as follows:

87 (1) Notwithstanding any other Act of Parliament or any Act of the legislature of a province, but subject to section 83 and section 5 of the First Nations Fiscal Management Act, the following property is exempt from taxation:

(a) the interest of an Indian or a band in reserve lands or surrendered lands; and

(b) the personal property of an Indian or a band situated on a reserve.

(2) No Indian or band is subject to taxation in respect of the ownership, occupation, possession or use of any property mentioned in paragraph (1)(a) or (b) or is otherwise subject to taxation in respect of any such property.

[subsection 3 omitted]13

As mentioned, the Act of 1850 spoke of taxes in general, while the modern Indian Act, maintaining a change introduced in 1876, emphasizes real and personal property. However, in its Nowegijick decision of 1983, the Supreme Court of Canada decided that income was included in the concept of property. Chief Justice Dickson wrote for a unanimous court that “treaties and statutes relating to Indians should be liberally construed and doubtful expressions resolved in favour of the Indians,”14 so income of Indians on reserve should be subject to the same exemption from taxation as real and personal property.

This decision is questionable from a historical point of view. Parliament passed new legislation in 1876 to focus the tax exemption for Indians on real and personal property, using wording that seems obvious. Taxation of income in Canada was not introduced until 1917, and Parliament amended the Indian Act in major and minor ways many times after 1917. If it wanted to exempt Indians from paying income tax, it could easily have amended the wording of the Indian Act to make that clear. Several generations of politicians apparently had no desire to absolve Indians from paying income tax in the same way

as other Canadians do. Thus, the expansion of Indians’ tax privilege beyond property to include income tax and sales taxes rests on a combination of judicial innovation and administrative practices rather than on the decision of Members of Parliament.

Once established by Nowegijick, the exemption for income tax was expanded through further judicial and administrative decisions. A Supreme Court opinion in Williams v. Canada (1992),15 which had to do with Unemployment Insurance benefits, created the “connecting factors test” for determining whether income was sufficiently connected to a reserve to be non-taxable. The way this test is now applied by the Canada Revenue Agency, the income of Registered Indians working off reserve is non-taxable if they are serving other Indians normally resident on reserve, if their work is non-commercial, and if the head office of the entity for which they work is located on reserve.16 Many First Nations and tribal organizations now have offices in cities employing social workers, counsellors, psychologists, and other staff to serve the needs of Registered Indians in these cities. An unknown number of these employees would be exempt from income tax.

Another income tax issue concerns the status of so-called “settlement trusts,” which are used to hold the proceeds of specific claims and modern treaties. The aggregate value of such trusts is not a matter of public record, but it must be in the tens of billions of dollars, given what is known about specific claims and modern treaties.c At the present time the trusts are treated as the property of the First Nations who have received the settlements and are not taxed.17 This seems fair as far as the original settlements are concerned, for they are supposed to be compensation for previously existing property rights. However, it is less clear that the investment earnings of such trusts should be exempt from taxation. Current policy has created a large and growing island of tax avoidance in the Canadian tax system.

Attempts to construe the tax exemption for Indians as a treaty right have so far failed. Taxation is not mentioned in the text of any historical treaty. The only place where it is cited in supporting documents is in the Treaty 8 commissioners’ report. The commissioners wrote that many Indians “were impressed with the notion that the treaty would lead to taxation,” so the commissioners “assured them that the treaty did not open the way to the imposition of any tax.”18 These words became central to the case of Benoit v. Canada, finally resolved by the Federal Court of Appeal in 2003.19

Gordon Benoit was a Treaty 8 Indian in northern Alberta who lived off reserve and made a living as an operator of heavy equipment. With the backing of several tribal organizations, Benoit argued that the commissioners’ report of what they had said during the treaty negotiations, supported by oral tradition, guaranteed immunity from taxation off reserve. Benoit prevailed at trial, but the decision was reversed by the Federal Court of Appeal, which found that the trial judge had given too much weight to oral tradition contradicted by documentary sources: “there is insufficient evidence to support the view that the Aboriginal signatories understood that they would be exempted from taxation at any time and for any reason.”20 d

The Indian Advancement Act of 1884 authorized the federal cabinet to declare individual bands to be in an advanced state of development and thereby able to exercise powers not mentioned in the Indian Act. One of these powers was taxation of property on reserve held by members by means of a location ticket or in fee simple after enfranchisement.21 That provision was carried forward in the 1951 revision of the Indian Act: “…the assessment and taxation of interests in land in the reserve of persons lawfully in

possession thereof,” again after a declaration by the federal cabinet that the band was “in an advanced state of development.”22 The phrase “lawfully in possession” was a term of art referring to certificates of possession, which were introduced in the 1951 revisions, replacing location tickets as a limited form of property ownership for Indians on reserve.

In 1988, Parliament added a new subsection to s. 83 of the Indian Act, allowing band councils to levy property tax not only on certificates of possession, but the council of a band may, subject to the approval of the Minister, make by-laws for … taxation for local purposes of land, or interests in land, in the reserve, including rights to occupy, possess or use land in the reserve.23

This broader wording allowed taxation not just of certificates of possession, which could be held only by band members, but also of leaseholds held by outside parties for residence, commerce, or transportation and communications infrastructure. Such taxes would have to be imposed by the band council and approved by the minister. The governor-in-council (federal cabinet) retained the right to regulate these taxes. As the first Indian-led amendment to the Indian Act, it is often referred to as the Kamloops Amendment, because the leadership came from Manny Jules, then Chief of the Kamloops Indian Band, who got the support of 120 First Nations to ask for the amendment.24

The main purpose of the legislation was to allow First Nations to levy property tax on reserve leaseholds, including residential and commercial developments, mining and forestry leases, and transportation and communication rights of way, such as railways, pipelines, and hydropower. It was a pro-development measure because it encouraged First Nations to look at their land in an economically rational way as a revenue-producing asset. It also provided band councils who passed tax bylaws with stable revenues that could be used to provide better services to on-reserve businesses and residents. An important feature of the legislation was the establishment of a collective institution, the Indian Taxation Advisory Board, of which Manny Jules was appointed head.

Jurisdiction over taxation was enlarged in 2005 with passage of the First Nations Fiscal Management Act (FMA), which gave band councils the power to impose, in addition to property taxes, the “taxation of business activities on reserve lands,” “development cost charges,” and “fees for the provision of services or the use of facilities on reserve lands, or for a regulatory process, permit, licence or other authorization, in relation to water, sewers, waste management, animal control, recreation and transportation, as well as any other similar services.” The legislation also replaced the Indian Taxation Advisory Board with the First Nations Tax Commission (FNTC),26 with Manny Jules remaining as chief commissioner. The new commission was given the power to approve First Nations’ property tax bylaws,27 thus obviating the need for recourse to the minister. The commission has developed model laws, and it guides First Nations through the process of adopting their own laws, thus providing expertise that few First Nations could develop on their own. The Federal Court of Canada has upheld the authority of participating First Nations to levy taxes and of the FNTC to approve them.28

As of February 2022, 130 First Nations had adopted tax bylaws under the FMA, while another 30 still relied on s. 83 of the Indian Act to levy property taxes. Almost all 160 First Nations were actively collecting taxes,29 bringing in a total of $80 million under the FMA and $24 million under s. 83.30 Over 92 percent of the FMA revenue came from property tax, with the remainder divided among property transfer taxes and various development and utility fees.31 These are small amounts in view of the size of reserves across Canada, but they reflect the relatively low state of development on most Indian lands.

Over 80 percent of this tax revenue is raised in British Columbia, and even within that

province proceeds are highly concentrated: Two First Nations—Westbank, with reserves in the Okanagan, and Squamish, with reserves in the BC lower mainland—accounted for over one-quarter of the $96 million in revenue; over one-half was raised by just 10 nations. Among First Nations reporting their tax revenue in the First Nations Gazette, the median amount of revenue raised in 2019 was approximately $130,000, and the majority of First Nations in Canada do not collect any property taxes at all.32

Statistical analysis has shown a positive association between having a property tax system and a higher Community Well-Being score,33 but there are questions about causation. Does enacting property tax lead to a higher standard of living, or does a higher standard of living lead to enacting a property tax because there is more worthwhile property to tax? Regardless of causation, property taxation has become a common feature of better organized, more prosperous First Nations.

Quebec lawyer Audrey Boissonneault has argued that the First Nations’ property tax system is too controlled by the federal government, which has retained authority to enact regulations and to appoint members of the regulatory commission. She proposes that First Nations themselves should choose members of the First Nations Tax Commission, and that the commission be only advisory. In her view, a robust understanding of self-government means that individual First Nations should have the right to devise their own tax systems without external approval.34 In contrast, André Le Dressay, an economist

whose specialty is the study of First Nations’ economies, defends the current regime as a story of success in enlarging the fiscal base of First Nations.35

Property taxes yield useful amounts of revenue for a minority of First Nations, but the approximately $100 million a year is a drop in the bucket compared to the more than $29 billion that the federal government appropriated for Indigenous spending in Budget 2023.36 For those First Nations that adopt it, property tax fosters a better understanding of the economic value of land and is often tied in with a more rational approach to budgeting and better training of budget officers. The supervisory role of the First Nations Tax Commission helps prevent the political abuse of taxation to exploit leaseholders, who cannot vote in band elections. Property taxes, however, are imposed largely upon leases for residential and vacation property, business premises, and transportation and utility corridors. A few of the leaseholders may be First Nations people (no statistics have been reported), but most are probably not members of First Nations. Thus, First Nations property tax seems to be largely taxation of other people rather than self-taxation.

Other taxes

There are three other forms of on-reserve taxation in which Registered Indians may be called upon to pay something. One is the so-called First Nation Tax, announced in the 1997 federal budget.37 The federal government negotiates agreements with willing First Nations to suspend GST payments on alcohol, tobacco products, and fuels purchased on reserve. The Canada Revenue Agency then administers a sales tax imposed by the First Nation at the rate of the GST upon those products sold on reserve, whether purchased by Registered Indians or other buyers, and remits the total amount to the First Nation.

At the time of writing, eight agreements had been concluded. I was able to find data for revenue generated by the tax for five First Nations in 2020. The amounts ranged from $0.86 million to $3.57 million, with a mean of $1.8 million. To put those figures in context, the 2020 revenue budgets of these five First Nations ranged from about $7 million to $69 million, with an average of $38.4 million.e Thus, the First Nation Tax generated about 4.6 percent of the total revenue enjoyed by these five bands in 2020—a useful supplement, but not a game-changer.

It is an important development that Registered Indians are explicitly required to pay the tax when they shop, but most of the revenue surely comes from other people buying products from businesses located on reserve lands. For example, Westbank First Nation, with only 855 members, generated sales tax revenue of $2.04 million in 2020.38 Although precise numbers are not available, the First Nation Tax is obviously a good deal for the signatory First Nations because the Canada Revenue Agency essentially collects on behalf of the First Nation the GST revenue that it used to collect for Canada and then

transfers it to the band government. So, the First Nation is taxing its own members to a small extent but taxing Canada to a greater extent. To illustrate the profitability of the scheme, the Cowichan Tribes distribute all the proceeds of what they call the “Tobacco Tax” to members:39 $3.6 million in 2020 divided among 5,600 members.

Somewhat similar but more comprehensive is the First Nations GST, for which the band government signs an agreement with the federal government to impose the GST at the same rate and with the same exemptions as elsewhere in Canada. The rate is the same as with the First Nations Tax, but the revenue potential is greater because more commodities are involved. As with the First Nations Tax, Canada is offering a substantial inducement by bearing administrative expenses while transferring foregone GST revenue to the band government.

Thirty-seven First Nations and one Inuit corporation have signed agreements to impose the First Nations GST. However, I could find data on only eight cases. Most of the bands that have signed onto the First Nations GST did so through larger self-government agreements, which means they do not file annual financial reports in the First Nation Profiles, while others fail to file for different reasons. Of the eight cases for which I found data, the smallest revenue earned in 2020 was $201,688, while the largest sum was $2,569,614. The total of $5.8 million constituted about 8.8 percent of the revenue budget of these eight First Nations. In comparison to the 4.6 percent of total revenue generated by the First Nations Tax, the First Nations GST seems to demonstrate greater revenue potential.

Finally, there is the First Nations Personal Income Tax (FNPIT), which has been implemented by 15 First Nations that have signed modern treaties40 according to which their “settlement lands” do not have reserve status and therefore do not qualify for the s. 87 exemption. Adopting the FNPIT allows them to fill the tax space otherwise occupied by the federal government. As with sales taxes, the Canada Revenue Agency collects the taxes and remits the revenue to the First Nation governments. The First Nation imposes only the federal rate of income tax except in the Yukon, where they have an agreement to impose the territorial rate as well.41 The people who pay the FNPIT are largely members of the First Nation living on the settlement lands, and the proceeds are remitted back to the First Nation government. Given that these taxpayers are mainly employees of the First Nation government or of its business entities, the FNPIT is a partially circular operation in which money is paid to employees in the form of salaries or wages and then returned to the First Nation in the form of FNPIT revenues.

Correspondence from an official in the Department of Finance, which administers these taxes, summarizes the aggregate picture for 2020:42

Currently there are 38 FNGST agreements, 15 FNPIT agreements, and 8 FNST agreements.

Total remittances in respect of the 2020 tax year for each type of agreement were as follows:

FNGST $20,095,327

FNPIT 32,889,870

FNST 6,895,774

The total is close to $60 million. Exact figures are not available, but it is reasonable to think that most of the revenue from the two sales taxes come from non-Indians shopping on reserves where stores and shopping centres are located. Given the government-dominated nature of most First Nation economies, income tax revenue probably comes mainly from members who are employed directly or indirectly by First Nation governments.

Let us look first at effects that have been arguably positive for First Nations:

Preservation of Reserve Land. Historical evidence suggests that the aim of the s. 87 exemption as well as its predecessors was to protect reserve land from takeover by municipal or provincial governments through seizure for unpaid taxes. That aim has been fulfilled; I know of no tax levied on reserve land by local governments, and no loss of reserve land to local governments for unpaid taxes. The reserve land base has sometimes been diminished by sales or other transfer to the federal government or by

undercounting of band population when the reserve was allocated, but that has nothing to do with taxation.

Tax-Free Economic Zones. Creation of tax-free economic zones has been recommended elsewhere as a pathway for faster economic development.43 Every Indian reserve in Canada is a tax-free economic zone, yet most are certainly not hotbeds of economic development. However, a small number, perhaps a few dozen out of the 630-plus First Nations, have achieved prosperity through business success, hosting casinos, hotels, residential and commercial real estate developments, and industrial investment. Wellknown examples are the Westbank First Nation (residential and commercial real estate), the Fort McKay First Nation (oil and gas service industries), the Whitecap Dakota First Nation (hospitality), the Membertou (commercial real estate and band-owned businesses), and the Tsuut’ina Nation (casino gambling). While it seems obvious that tax-exempt status must have been an aid to business success, no detailed study of this topic exists. It is also obvious that tax exemption alone is not enough to achieve success, as most First Nations are still mired in poverty. The First Nations that have succeeded seem to have aggressively exploited local economic opportunities.44

Now let us look at some areas where the tax exemption for Registered Indians living on reserve seems to have had no effect at all, or possibly even a negative effect.

Tax Credits. Both the GST/HST and the carbon tax come with valuable tax credits or rebates for low-income people, but one must file a tax return to collect the benefits.45 Indians pay GST/HST when they shop off reserve, and like all other Canadians they pay the carbon tax because it is an excise tax incorporated into the sale price of commodities. One First Nations leader has written that Indians on reserve often do not file tax returns because they do not have to pay income tax, and thus do not get the credits for which they are eligible.46 The author provides no data on how many Indians fail to file tax

returns, but it seems possible that incentives created by the income tax exemption may lead to some losses for some people. However, it is not expensive to file a simple return with no tax owing, and band governments should be able to assist their members if necessary. If a practical problem exists, it can be fixed without legislation.

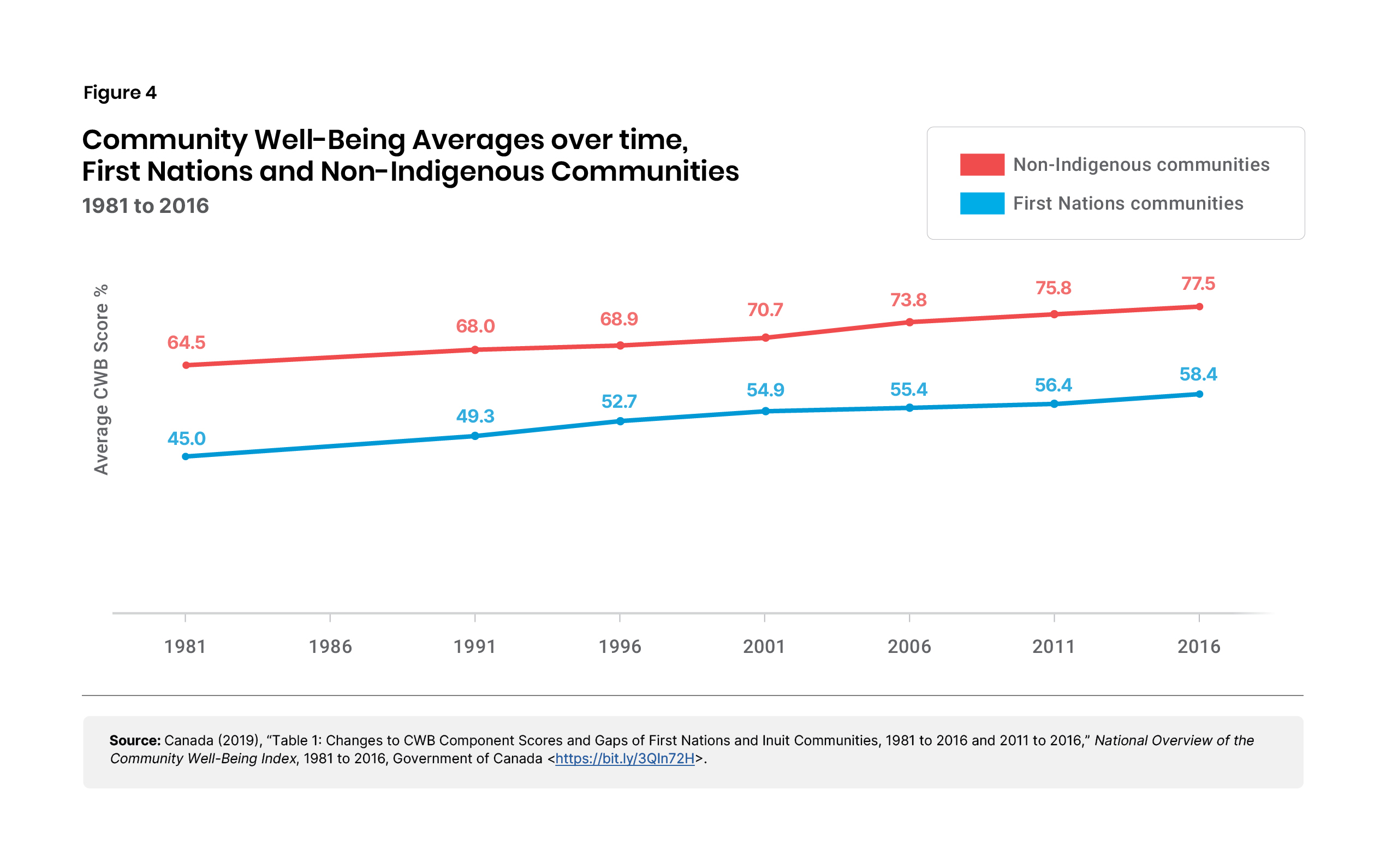

Standard of Living. One measure of the standard of living is the Community Wellbeing Index (CWB), computed every five years using Statistics Canada data. The CWB aggregates data on housing, education, employment, and income. As Figure 4 shows, the measured gap between Indian reserves and other Canadian communities has remained more or less constant since data were first collected:47

The gap was 19.5 points in 1981 and 19.1 points in 2016. The Canadian economy is a tide that lifts all boats, but Indian reserves remain further out to sea, so to speak.

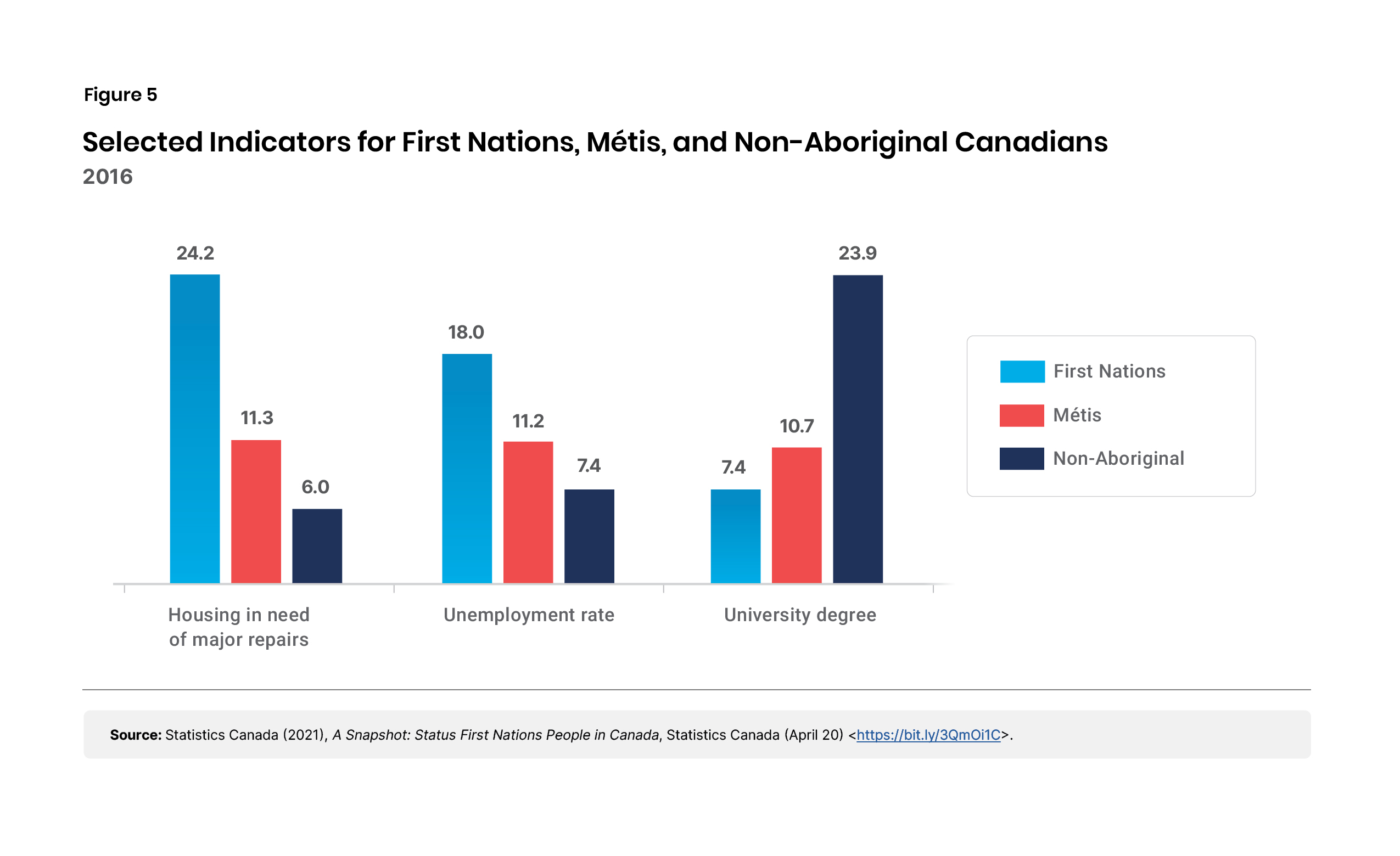

In data compilations, Indians generally occupy a less favourable position than Métis, who in turn fall below non-Aboriginal Canadians. Figure 5 gives an example from 2016 data.48

The data in Figure 5 is not perfect for our purposes because it does not differentiate between Registered Indians living on reserve, who benefit from tax exemptions, and Indians living off reserve, who usually do not. However, in both 2006 and 2016, Indians living on reserve scored below Indians living off reserve in unemployment, income, education, and housing. The conclusion is inescapable that the tax exemption has not improved measurable aspects of living standards on reserve as compared to living off reserve.

Quality of Governance. In an influential paper, John Graham and Jodi Bruhn argued that the governance of First Nations was detrimentally affected by a lack of accountability to members. They drew many comparisons with states in the Third World whose revenues come mainly from taxes and royalties on natural resources, especially oil, rather than from taxes on their own citizens. The authors argued that because First Nation members did not support their government directly, they had weaker incentives to monitor their government’s performance for efficiency and integrity.49

Statistical research suggests that enactment by a First Nation of a property tax system is modestly correlated with a higher CWB score, even after controlling for other variables.50 Most of the revenue from First Nation property taxes comes from non-members, so they do not strictly fit the Graham-Bruhn argument; but they do point in that direction by making members more aware of the economic value of their reserve land. I also found that First Nations that offered higher-than-average compensation to council members (but not to chiefs) tended to have a lower CWB score.51 My tentative explanation for

this finding, which needs further testing, is that higher compensation for councillors makes those positions more valuable, which in turn encourages the politicization of band government through patronage and nepotism, fitting in nicely with the familial culture of most First Nations.

The Graham-Bruhn theory predicts that introduction of taxation would be a move in the right direction to decrease patronage, nepotism, and corruption. No federal government has been willing to take such a radical step, but the Harper government did try to encourage transparency by leading Parliament to adopt the First Nations Financial Transparency Act in 2013,52 which requires First Nations operating under the Indian Act (about 580) to file annual audited accounts including remuneration of chief and council. These statements are then published in the First Nation Profiles maintained by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.53 The Liberal government of Justin Trudeau announced that it would not enforce compliance by withholding grants,54 but most First Nations do in fact still comply.

There is no overall list or ranking of corruption in First Nation governments. When I wrote about this subject in 2016, a ten-minute Internet search was able to turn up seven quite serious instances of corruption occurring in 2015-16.55 By comparison, a quick Internet search in late 2022 showed one allegation from 2017,56 plus unsubstantiated charges of corruption in the Assembly of First Nations57 and the existence of a small organization devoted to fighting corruption in reserve government, but without any particulars.58 Has Harper’s Financial Transparency Act had a positive effect? Perhaps, or perhaps media attention has shifted for other reasons. The evidence does not allow for a definitive

answer.

Although the empirical evidence from First Nations in favour of the Graham-Bruhn argument about the link between taxation and good governance is incomplete, the argument itself is plausible and supported by evidence from elsewhere. It seems worthwhile, in my opinion, to move in the direction of taxation for First Nations.

Resentment. It is obvious that many Canadians have a degree of resentment about the s. 87 tax exemption. Websites and media articles abound attempting to explain that Indians really do pay taxes.59 These articles usually admit the truth, namely that Registered Indians on reserve are exempt from taxation, but emphasize another truth, namely that this group is only a subset of Indigenous people as a whole.

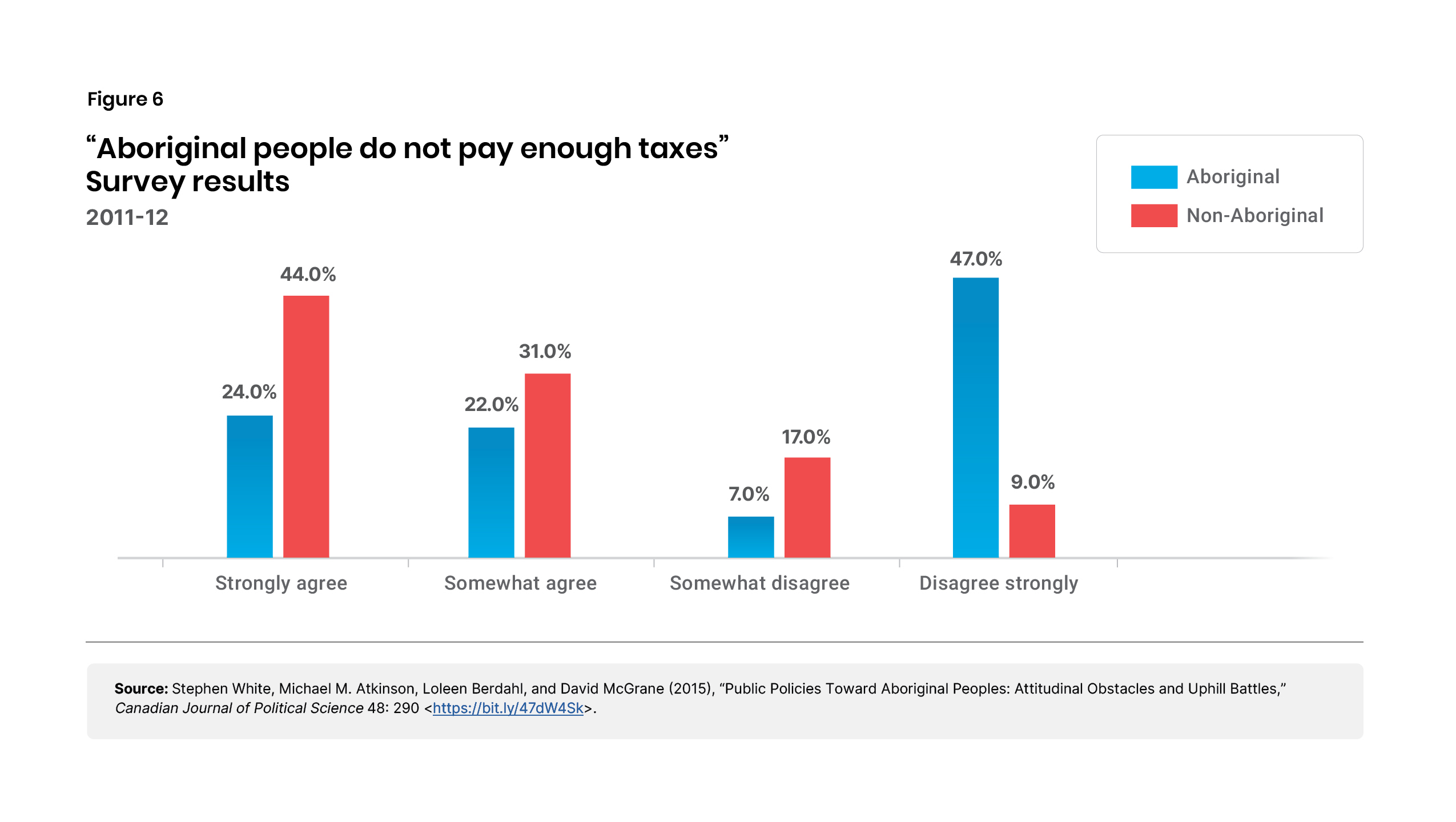

Survey research carried out in Saskatchewan in 2011-12 gives an idea of the degree of resentment caused by the tax exemption (see Figure 6). Seventy-five percent of non-Aboriginal respondents agreed with the statement that “Aboriginal people do not pay enough tax.” Indeed, 44 percent strongly agreed with the proposition. Strikingly, Aboriginal respondents did not disagree as strongly as one might expect. Forty-six percent agreed (24 percent strongly and 22 percent somewhat) and 54 percent disagreed (47 percent strongly and 7 percent somewhat).60 Although the data were not reported, the disagreement among Aboriginal respondents may have reflected the different tax status of Registered Indians on reserve versus Métis and off-reserve Indians.

Non-Aboriginal respondents in the study answered a range of questions showing they believed Indigenous people should be treated equally and in the same way as other Canadians and should not receive special status or privileges. Thus, the dislike of the s. 87 tax exemption is anchored in a larger matrix of beliefs about equality before the law, and the tax status of Registered Indians on reserve easily becomes a flashpoint for resentment.

Loss of Revenue. Existence of a tax exemption makes it seem probable that revenue to governmental treasuries will be reduced in some measure. One can think of theoretical exceptions—e.g., a carefully targeted exemption for entrepreneurs who create so much additional business activity with so many taxed salaries that the public treasury benefits—but that seems to have little relevance to the reality of the s. 87 exemption.

Let us look first at property taxes. In Canada, what is collected from ratepayers is generally split between local and provincial governments, with nothing going to the federal government. It seems reasonable that the provincial governments should get a share of the revenue because they provide many services directly to taxpayers, such as building roads and educational facilities, and funding health care. But, for constitutional reasons, the federal government, not provincial governments, provides services to people who live on Indian reserves. Thus, provincial governments would not be logically entitled to any share of property taxes collected on reserve. The federal government might logically claim a share but in practice has vacated the field to band governments, which seems compatible with the Canadian government’s often-stated commitment to self-government of First Nations.

The problem, then, is that First Nations are not making full use of their legislated authority to levy property tax. Only a little over a quarter of First Nations have implemented a property tax system, and those that have done so are mainly taxing interests in property held by non-members, such as pipelines, utility and railway corridors, business parks, and residential developments.

It is anyone’s guess how much revenue could be raised if band councils taxed other lands. Most of these would be band lands, so the government would be taxing itself with no net benefit. Some houses and agricultural properties are owned by band members under certificates of possession, but no estimate exists of the value of these properties, how much is already being paid in property tax, and how much additional revenue could be raised if property tax were applied more widely and consistently.

Adoption of property tax by the three-quarters of First Nations that currently do not use it would be a promising development but probably would not raise much revenue, at least initially. These First Nations would include many impoverished bands with no business interests to tax and lots of substandard housing of little value and probably owned by the band itself.

In short, First Nations could benefit financially from the extension of property tax, but the amount raised will be limited by their poverty and by the fact of so much band ownership of land. Additional use of certificates of possession or some other form of private property will be required to raise substantial additional revenue through property tax, even if band councils make the decision to levy property tax on their own members.

Although the Department of Finance lists the s. 87 exemption as a tax expenditure, it publishes no data on the revenue foregone, which prevents proper analysis of the costs and benefits of the exemption.61 One estimate is that application of the tax exemption to sales and income taxes caused a loss of $1,272.2 billion to public revenues in fiscal 2014-15.62 Of that amount, $432.3 million would have been provincial revenue from sales taxes, or just over 1/3 of the total. The study did not try to separate provincial and federal components of income tax revenues, so I will somewhat arbitrarily raise the 1/3 provincial share to 2/5 of the overall total, or $508.9 million, leaving the federal portion of lost revenue at $763.3 million. There is, however, a large unknown here—the amount of revenue lost through application of the exemption through the connecting factors test to Registered Indians working and living off reserve. It should be noted, also, that this study was a graduate-school research project and the author was not an economist. This would be an important topic for future treatment by a professional economist.

Budget 2014 projected revenue of $276.3 billion for fiscal 2014-15,63 so the loss to the federal treasury of $763.3 million through the s. 87 exemption was about 0.3 percent of total revenue—pretty much a rounding error in the overall scheme of things. The absolute numbers would undoubtedly be larger if a simulation were done for 2022-23, but the percentages would probably not be much different. So, the problem with the s. 87 exemption is not so much the extra burden it places on federal taxpayers—that burden is real but relatively small—as its other effects. Note, however, that no data are available for tax revenue lost by the exemption of settlement trusts and their investment earnings. Thus the total revenue lost may be considerably greater than what can be estimated from publicly available data.

Registered Indians buying automobiles off reserve can sometimes get dealers to deliver the vehicle to a reserve for pickup, thereby allowing the purchaser to escape GST/HST and any sales taxes buried in the sale price.64 In such instances, provinces lose HST revenue that should have been theirs. Also, Canada has a growing number of urban reserves. These typically sign an agreement with the host municipality to pay a gratuity in lieu of property tax, thus rendering the city whole.65 However, the urban reserves usually host retail stores that make it easy for Registered Indians living off reserve to shop without paying sales taxes, again producing some loss to provincial tax revenues. However, total provincial and territorial revenues in 2014 were $497 billion;66 thus, the loss to the provinces is about 0.1 percent of their total revenues.

Canadian government policy has long been to leave in place the s. 87 exemption, as interpreted by the Supreme Court to include sales and income tax, for most First Nations, but to require those wanting to pursue modern treaty or self-government agreements to give up the exemption while instituting their own systems of property, sales, and income taxation. This has led to the 38 First Nations GST and 15 First Nations Personal Income Tax agreements mentioned earlier. However, the government is now changing direction. In a media release on July 22, 2022, Marc Miller, then Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, announced a new policy:

Since becoming minister, I have heard very clearly from across the country that the discontinuance of section 87 of the Indian Act and the removal of the federal tax exemption on First Nations’ reserve lands is a significant disincentive to advancing self-government, a divisive issue within communities that have recently signed Modern Treaty arrangements, and a material barrier to signing Modern Treaties.

The tax exemption will be available for continuation on Indigenous governments’ former reserves and on other First Nations reserves in Canada for prospective and existing Modern Treaty beneficiaries who are registered pursuant to the Indian Act.67

Nothing is definite here as the announcement foresees further consultation with First Nations. However, it is probable that First Nations who gave up the s. 87 exemption when they entered modern treaties or self-government agreements will demand that it be reinstated, while First Nations considering modern treaty or self-government arrangements will demand that s. 87 continue to apply to them. What will happen to existing or future sales and income tax agreements is unforeseeable at this point.

Amid this uncertainty, I suggest taking policy in a different direction. I can summarize my proposals in three main points:

First, the federal government should revise s. 87 of the Indian Act so that it applies only to land. The main function of the section was always to protect reserve land from taxation and seizure by local or provincial governments, so this protection will continue, even though the wording of the new section 87 should make it clear that “property” means real property only and does not include either personal property or income. This step will require an active strategy of explanation as many First Nation governments can be expected to oppose it.

Such an amendment will amount to overturning the Supreme Court’s 1983 Nowegijick decision. There will be political opposition to this, but there is no real legal obstacle.

The Supreme Court in that decision was interpreting legislation, i.e., the Indian Act, so Parliament can pass new legislation if it wishes.

It should also be made clear that personal property is not included in the exemption. Capital gains tax applies to increases in the value of personal-use property, but most such property (think of clothes, automobiles, athletic gear, and so on) decreases in value over time rather than increases. Works of art, jewelry, stamps, and other luxury and collectors’ items may increase in value, and there is no good reason to make Indian reserves tax-free havens for speculation. Canada has also recently introduced a luxury tax on vehicles priced over $100,000 and boats priced over $250,000,68 and again, there is no good reason why Indian reserves should be tax havens for such luxuries.

Second, the Canadian government should extend federal income tax, as well as sales, excise, and value-added taxes to all Indian reserves. However, a portion of revenue from such taxes should be returned to the First Nation after it signs a tax administration agreement. As with existing FNGST and FNPIT agreements, the Canada Revenue Agency will administer the tax and return the revenue to the First Nation government. In the case of personal and corporate income taxes, the First Nation will be free to charge only the federal rate, thus leaving a bit of tax advantage for its citizens. Canada should not necessarily imitate American policies, but it is noteworthy that the personal income of Indians in the United States has been subject to federal taxation ever since Indians received American citizenship and the right to vote in 1924.69

Clarifying that income earned on reserve is now subject to taxation will do away with the connecting factors test, which has become Byzantine in its complexity due to judicial and administrative rulings. Academic interpreters agree on this point, even though some would like to make the s. 87 exemption more rather than less generous to First Nations and possibly even include other Indigenous people in its application.70

Third, as these will be major and probably controversial changes, there will need to be a period of adjustment. This creates a risk that an opposition party may win an election during the adjustment period and repeal the legislation or suspend enforcement of the new regime while leaving the law in place. Something like this happened to the enforcement of the First Nations Financial Transparency Act when the Liberals came to power in 2015. It would, therefore, be highly desirable to seek multiparty support for the legislation required to establish the new taxation regime for First Nations.

These changes would deal in a measured way with the unfortunate consequences of the s. 87 exemption in its current form. They would eliminate the exemption from taxation of income on Indian reserves, for which there never was a good policy foundation; but they would also return revenue to First Nations themselves, assisting their move towards real and not nominal self-government. At the same time, by leaving the exemption for taxation of property in place and supporting First Nations’ self-taxation of property, the changes would reinforce the federal commitment to protection of First Nation lands.

Removal of the exemptions for income and sales taxes combined with a public explanation of the rationale for the exemption from property tax would diminish the resentment that other Canadians feel because of privileges for which there was no good reason. Due to widespread poverty on Indian reserves, only a few band members would pay the new income tax, but all would pay GST and other federal sales taxes. Hopefully, such payments will engender greater interest by members in how the band government spends its revenues, leading to better, more informed participation by members. The effect might be small at first, but it would be in the right direction.

In short, these proposed changes to the tax regime for Indian reserves and Registered Indians are modest in impact, but they would help move First Nations in the direction of meaningful self-government, increase equality before the law, and reduce the resentment that many Canadians feel about the special privilege of immunity from taxation.

Tom Flanagan is a Senior Fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, Professor Emeritus of Political Science and Distinguished Fellow at the School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, and was elected to the Royal Society of Canada in 1996. He received his B.A. from Notre Dame and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Duke University. He taught political science at the University of Calgary from 1968 until retirement in 2013. He is the author of multiple books and articles on topics such as Louis Riel and Métis history, aboriginal rights and land claims, Canadian political parties, political campaigning, and applications of game theory to politics. His books have won six prizes, including the Donner-Canadian Prize for best book of the year in Canadian public policy. Prof. Flanagan has also been a frequent expert witness in litigation over aboriginal and treaty land claims.

Image credits: iStock

The logo and text are signs that each alone and in combination are being used as unregistered trademarks owned by the Aristotle Foundation. All rights reserved.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

are signs that are each alone and in combination are being used as unregistered trademarks owned by the Aristotle Foundation. All rights reserved.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER